Test-Driving HTML Templates

source link: https://martinfowler.com/articles/tdd-html-templates.html

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Level 2: testing HTML structure

What else should we test?

We know that the looks of a page can only be tested, ultimately, by a human looking at how it is rendered in a browser. However, there is often logic in templates, and we want to be able to test that logic.

One might be tempted to test the rendered HTML with string equality, but this technique fails in practice, because templates contain a lot of details that make string equality assertions impractical. The assertions become very verbose, and when reading the assertion, it becomes difficult to understand what it is that we're trying to prove.

What we need is a technique to assert that some parts of the rendered HTML correspond to what we expect, and to ignore all the details we don't care about. One way to do this is by running queries with the CSS selector language: it is a powerful language that allows us to select the elements that we care about from the whole HTML document. Once we have selected those elements, we (1) count that the number of element returned is what we expect, and (2) that they contain the text or other content that we expect.

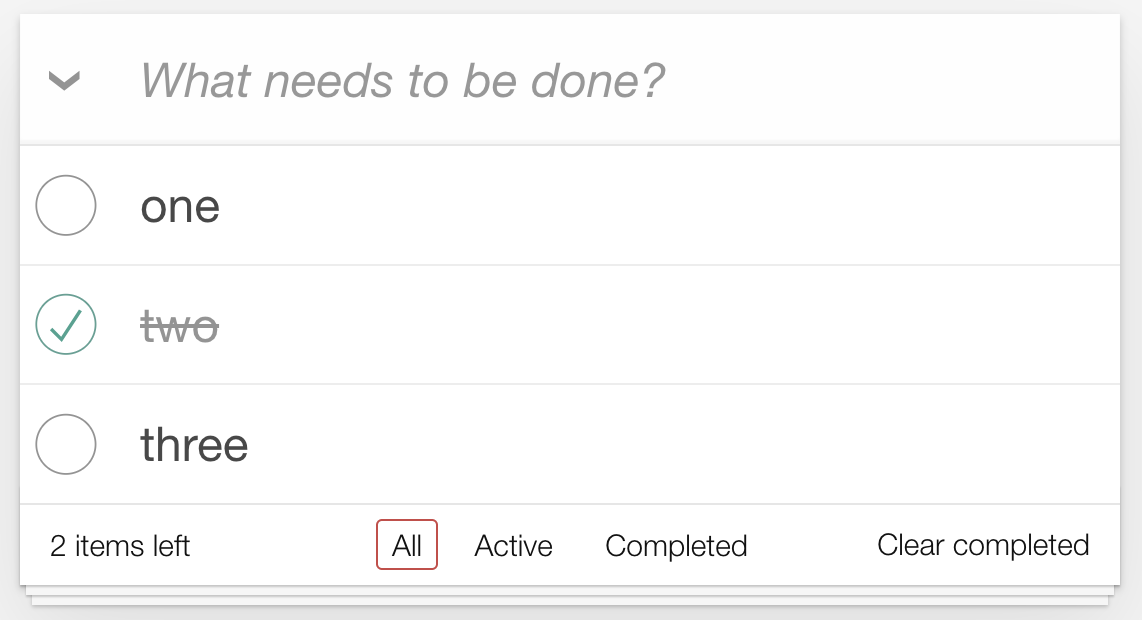

The UI that we are supposed to generate looks like this:

There are several details that are rendered dynamically:

- The number of items and their text content change, obviously

- The style of the todo-item changes when it's completed (e.g., the second)

- The "2 items left" text will change with the number of non-completed items

- One of the three buttons "All", "Active", "Completed" will be

highlighted, depending on the current url; for instance if we decide that the

url that shows only the "Active" items is

/active, then when the current url is/active, the "Active" button should be surrounded by a thin red rectangle - The "Clear completed" button should only be visible if any item is completed

Each of this concerns can be tested with the help of CSS selectors.

This is a snippet from the TodoMVC template (slightly simplified). I have not yet added the dynamic bits, so what we see here is static content, provided as an example:

index.tmpl

<section class="todoapp">

<ul class="todo-list">

<!-- These are here just to show the structure of the list items -->

<!-- List items should get the class `completed` when marked as completed -->

<li >

<div class="view">

<input class="toggle" type="checkbox" checked>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

<li>

<div class="view">

<input class="toggle" type="checkbox">

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

</ul>

<footer class="footer">

<!-- This should be `0 items left` by default -->

<span class="todo-count"><</span>

<ul class="filters">

<li>

<a href="#/">All</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="#/active">Active</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="#/completed">Completed</a>

</li>

</ul>

<!-- Hidden if no completed items are left ↓ -->

</footer>

</section>

The choice of CSS selector can affect the robustness of our tests.

Sometimes classes such as "completed" act as a contract between the visual designer and the programmer, linking CSS behaviour to the appropriate HTML elements.

We should look for CSS selector that will make evolution of the HTML and CSS easy, without breaking the template tests needlessly.

Some hints on how to write robust CSS selectors from Dan Mutton:

- Narrow the selector to target only the thing you care about and not information about how it is laid out on the page. Layout is much more likely to change and coupling your selector to it will make your test much more brittle.

For instance ul.todolist li

is more

flexible than section ul.todolist li

because

in the latter case if the <section> is changed to a

<div>, the test would break even though behaviorally

nothing changed.

For example, a submit button can be targeted as

button[type="submit"]

since in the majority of

cases a submit button must have the type="submit"

attribute in order to behave correctly, and must be of element

button in order to take advantage of native button

functionality. A class name .submitBtn is much more

likely to be changed or even removed if, for instance, it's being

used for other purposes like styling.

By looking at the static version of the template, we can deduce which CSS selectors can be used to identify the relevant elements for the 5 dynamic features listed above:

| feature | CSS selector | |

|---|---|---|

| ① | All the items | ul.todo-list li |

| ② | Completed items | ul.todo-list li.completed |

| ⓷ | Items left | span.todo-count |

| ④ | Highlighted navigation link | ul.filters a.selected |

| ⑤ | Clear completed button | button.clear-completed |

We can use these selectors to focus our tests on just the things we want to test.

Testing HTML content

The first test will look for all the items, and prove that the data set up by the test is rendered correctly.

func Test_todoItemsAreShown(t *testing.T) {

model := todo.NewList()

model.Add("Foo")

model.Add("Bar")

buf := renderTemplate(model)

// assert there are two <li> elements inside the <ul class="todo-list">

// assert the first <li> text is "Foo"

// assert the second <li> text is "Bar"

}

We need a way to query the HTML document with our CSS selector; a good library for Go is goquery, that implements an API inspired by jQuery. In Java, we keep using the same library we used to test for sound HTML, namely jsoup. Our test becomes:

func Test_todoItemsAreShown(t *testing.T) {

model := todo.NewList()

model.Add("Foo")

model.Add("Bar")

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", model)

// parse the HTML with goquery

if err != nil {

// if parsing fails, we stop the test here with t.FatalF

t.Fatalf("Error rendering template %s", err)

}

// assert there are two <li> elements inside the <ul class="todo-list">

assert.Equal(t, 2, selection.Length())

// assert the first <li> text is "Foo"

// assert the second <li> text is "Bar"

}

func text(node *html.Node) string {

// A little mess due to the fact that goquery has

// a .Text() method on Selection but not on html.Node

sel := goquery.Selection{Nodes: []*html.Node{node}}

return strings.TrimSpace(sel.Text())

}

@Test

void todoItemsAreShown() throws IOException {

var model = new TodoList();

model.add("Foo");

model.add("Bar");

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", model);

// parse the HTML with jsoup

// assert there are two <li> elements inside the <ul class="todo-list">

assertThat(selection).hasSize(2);

// assert the first <li> text is "Foo"

// assert the second <li> text is "Bar"

}

If we still haven't changed the template to populate the list from the model, this test will fail, because the static template todo items have different text:

--- FAIL: Test_todoItemsAreShown (0.00s)

index_template_test.go:44: First list item: want Foo, got Taste JavaScript

index_template_test.go:49: Second list item: want Bar, got Buy a unicorn

IndexTemplateTest > todoItemsAreShown() FAILED

org.opentest4j.AssertionFailedError:

Expecting:

<"Taste JavaScript">

to be equal to:

<"Foo">

but was not.

We fix it by making the template use the model data:

<ul class="todo-list">

<li>

<div class="view">

<input class="toggle" type="checkbox">

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

</ul>

Java - jmustache

<ul class="todo-list">

<li>

<div class="view">

<input class="toggle" type="checkbox">

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

</ul>

Test both content and soundness at the same time

Our test works, but it is a bit verbose, especially the Go version. If we're going to have more tests, they will become repetitive and difficult to read, so we make it more concise by extracting a helper function for parsing the html. We also remove the comments, as the code should be clear enough

func Test_todoItemsAreShown(t *testing.T) {

model := todo.NewList()

model.Add("Foo")

model.Add("Bar")

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", model)

selection := document.Find("ul.todo-list li")

assert.Equal(t, 2, selection.Length())

assert.Equal(t, "Foo", text(selection.Nodes[0]))

assert.Equal(t, "Bar", text(selection.Nodes[1]))

}

if err != nil {

// if parsing fails, we stop the test here with t.FatalF

t.Fatalf("Error rendering template %s", err)

}

@Test

void todoItemsAreShown() throws IOException {

var model = new TodoList();

model.add("Foo");

model.add("Bar");

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", model);

var selection = document.select("ul.todo-list li");

assertThat(selection).hasSize(2);

assertThat(selection.get(0).text()).isEqualTo("Foo");

assertThat(selection.get(1).text()).isEqualTo("Bar");

}

Much better! At least in my opinion. Now that we extracted the parseHtml helper, it's

a good idea to check for sound HTML in the helper:

func parseHtml(t *testing.T, buf bytes.Buffer) *goquery.Document {

document, err := goquery.NewDocumentFromReader(bytes.NewReader(buf.Bytes()))

if err != nil {

// if parsing fails, we stop the test here with t.FatalF

t.Fatalf("Error rendering template %s", err)

}

return document

}

private static Document parseHtml(String html) {

var document = Jsoup.parse(html, "", );

return document;

}

And with this, we can get rid of the first test that we wrote, as we are now testing for sound HTML all the time.

The second test

Now we are in a good position for testing more rendering logic. The

second dynamic feature in our list is "List items should get the class

completed when marked as completed". We can write a test for this:

func Test_completedItemsGetCompletedClass(t *testing.T) {

model := todo.NewList()

model.Add("Foo")

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", model)

document := parseHtml(t, buf)

assert.Equal(t, 1, selection.Size())

assert.Equal(t, "Bar", text(selection.Nodes[0]))

}

@Test

void completedItemsGetCompletedClass() {

var model = new TodoList();

model.add("Foo");

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", model);

Document document = Jsoup.parse(html, "");

assertThat(selection).hasSize(1);

assertThat(selection.text()).isEqualTo("Bar");

}

And this test can be made green by adding this bit of logic to the template:

<ul class="todo-list">

{{ range .Items }}

<div class="view">

<input class="toggle" type="checkbox">

<label>{{ .Title }}</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

{{ end }}

</ul>

Java - jmustache

<ul class="todo-list">

{{ #allItems }}

<div class="view">

<input class="toggle" type="checkbox">

<label>{{ title }}</label>

<button class="destroy"></button>

</div>

</li>

{{ /allItems }}

</ul>

So little by little, we can test and add the various dynamic features that our template should have.

Make it easy to add new tests

The first of the 20 tips from the excellent talk by Russ Cox on Go Testing is "Make it easy to add new test cases". Indeed, in Go there is a tendency to make most tests parameterized, for this very reason. On the other hand, while Java has good support for parameterized tests with JUnit 5, they don't seem to be used as much.

Since our current two tests have the same structure, we could factor them into a single parameterized test.

A test case for us will consist of:

- A name (so that we can produce clear error messages when the test fails)

- A model (in our case a

todo.List) - A CSS selector

- A list of text matches that we expect to find when we run the CSS selector on the rendered HTML.

So this is the data structure for our test cases:

Note how the array initializer syntax, in both Go and Java, allows a trailing comma after the last item

in the sequence of test cases. This makes it easier to create a new test case by copying, pasting and

modifying an existing one, with no need to adjust commas. This is why we used an array in Java instead of

List.of or Stream.of: with those, we would have to take care to remove the

trailing comma from the last item, and this slows down the developers.

var testCases = []struct {

name string

model *todo.List

selector string

matches []string

}{

{

name: "all todo items are shown",

model: todo.NewList().

Add("Foo").

Add("Bar"),

selector: "ul.todo-list li",

matches: []string{"Foo", "Bar"},

},

{

name: "completed items get the 'completed' class",

model: todo.NewList().

Add("Foo").

AddCompleted("Bar"),

selector: "ul.todo-list li.completed",

matches: []string{"Bar"},

},

}

The toString override makes the test output much clearer

record TestCase(String name,

TodoList model,

String selector,

List<String> matches) {

@Override

public String toString() {

return name;

}

}

public static TestCase[] indexTestCases() {

return new TestCase[]{

new TestCase(

"all todo items are shown",

new TodoList()

.add("Foo")

.add("Bar"),

"ul.todo-list li",

List.of("Foo", "Bar")),

new TestCase(

"completed items get the 'completed' class",

new TodoList()

.add("Foo")

.addCompleted("Bar"),

"ul.todo-list li.completed",

List.of("Bar")),

};

}

And this is our parameterized test:

The t.Run call runs a subtest with the given name.

func Test_indexTemplate(t *testing.T) {

for _, test := range testCases {

t.Run(test.name, func(t *testing.T) {

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", test.model)

assertWellFormedHtml(t, buf)

document := parseHtml(t, buf)

selection := document.Find(test.selector)

require.Equal(t, len(test.matches), len(selection.Nodes), "unexpected # of matches")

for i, node := range selection.Nodes {

assert.Equal(t, test.matches[i], text(node))

}

})

}

}

I usually advise against using if or for in test code,

but in parameterized tests, I think the added complexity is compensated by the

simplicity we gain in the test cases.

@ParameterizedTest

@MethodSource("indexTestCases")

void testIndexTemplate(TestCase test) {

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", test.model);

var document = parseHtml(html);

var selection = document.select(test.selector);

assertThat(selection).hasSize(test.matches.size());

for (int i = 0; i < test.matches.size(); i++) {

assertThat(selection.get(i).text()).isEqualTo(test.matches.get(i));

}

}

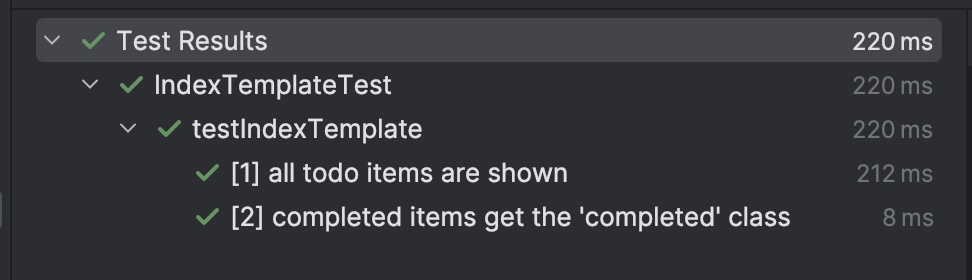

We can now run our parameterized test and see it pass:

$ go test -v

=== RUN Test_indexTemplate

=== RUN Test_indexTemplate/

=== RUN Test_indexTemplate/

--- PASS: Test_indexTemplate (0.00s)

--- PASS: Test_indexTemplate/ (0.00s)

--- PASS: Test_indexTemplate/ (0.00s)

PASS

ok tdd-html-templates 0.608s

$ ./gradlew test > Task :test IndexTemplateTest > testIndexTemplate(TestCase) > [1] PASSED IndexTemplateTest > testIndexTemplate(TestCase) > [2] PASSED

Note how, by giving a name to our test cases, we get very readable test output, both on the terminal and in the IDE:

Having rewritten our two old tests in table form, it's now super easy to add another. This is the test for the "x items left" text:

{

name: "items left",

model: todo.NewList().

Add("One").

Add("Two").

AddCompleted("Three"),

selector: "span.todo-count",

matches: []string{"2 items left"},

},

new TestCase(

"items left",

new TodoList()

.add("One")

.add("Two")

.addCompleted("Three"),

"span.todo-count",

List.of("2 items left")),

And the corresponding change in the html template is:

<span class="todo-count"><strong></strong> items left</span>

Java - jmustache

<span class="todo-count"><strong></strong> items left</span>

The above change in the template requires a supporting method in the model:

type Item struct {

Title string

IsCompleted bool

}

type List struct {

Items []*Item

}

public class TodoList {

private final List<TodoItem> items = new ArrayList<>();

// ...

}

We've invested a little effort in our testing infrastructure, so that adding new test cases is easier. In the next section, we'll see that the requirements for the next test cases will push us to refine our test infrastructure further.

Making the table more expressive, at the expense of the test code

Finding out which url is being visited cannot be done at template rendering time, especially if the template is rendered server-side. We could add a bit of JavaScript logic for this, but then how would we test it? The point of this article is to focus on testing the template at rendering time.

We will now test the "All", "Active" and "Completed" navigation links at the bottom of the UI (see the picture above), and these depend on which url we are visiting, which is something that our template has no way to find out.

Currently, all we pass to our template is our model, which is a todo-list. It's not correct to add the currently visited url to the model, because that is user navigation state, not application state.

So we need to pass more information to the template beyond the model. An easy way

is to pass a map, which we construct in our

renderTemplate function:

func renderTemplate(model *todo.List, path string) bytes.Buffer {

templ := template.Must(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

var buf bytes.Buffer

err := templ.Execute(&buf, )

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return buf

}

private String renderTemplate(String templateName, TodoList model, String path) {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream(templateName)));

return template.execute();

}

And correspondingly our test cases table has one more field:

var testCases = []struct {

name string

model *todo.List

selector string

matches []string

}{

{

name: "all todo items are shown",

model: todo.NewList().

Add("Foo").

Add("Bar"),

selector: "ul.todo-list li",

matches: []string{"Foo", "Bar"},

},

// ... the other cases

{

name: "highlighted navigation link: All",

selector: "ul.filters a.selected",

matches: []string{"All"},

},

{

name: "highlighted navigation link: Active",

selector: "ul.filters a.selected",

matches: []string{"Active"},

},

{

name: "highlighted navigation link: Completed",

selector: "ul.filters a.selected",

matches: []string{"Completed"},

},

}

record TestCase(String name,

TodoList model,

String selector,

List<String> matches) {

@Override

public String toString() {

return name;

}

}

public static TestCase[] indexTestCases() {

return new TestCase[]{

new TestCase(

"all todo items are shown",

new TodoList()

.add("Foo")

.add("Bar"),

"ul.todo-list li",

List.of("Foo", "Bar")),

// ... the previous cases

new TestCase(

"highlighted navigation link: All",

new TodoList(),

"ul.filters a.selected",

List.of("All")),

new TestCase(

"highlighted navigation link: Active",

new TodoList(),

"ul.filters a.selected",

List.of("Active")),

new TestCase(

"highlighted navigation link: Completed",

new TodoList(),

"ul.filters a.selected",

List.of("Completed")),

};

}

We notice that for the three new cases, the model is irrelevant; while for the previous cases, the path is irrelevant. The Go syntax allows us to initialize a struct with just the fields we're interested in, but Java does not have a similar feature, so we're pushed to pass extra information, and this makes the test cases table harder to understand.

A developer might look at the first test case and wonder if the expected behavior depends

on the path being set to "/", and might be tempted to add more cases with

a different path. In the same way, when reading the

highlighted navigation link test cases, the developer might wonder if the

expected behavior depends on the model being set to an empty todo list. If so, one might

be led to add irrelevant test cases for the highlighted link with non-empty todo-lists.

We want to optimize for the time of the developers, so it's worthwhile to avoid adding irrelevant

data to our test case. In Java we might pass null for the

irrelevant fields, but there's a better way: we can use

the builder pattern,

popularized by Joshua Bloch.

We can quickly write one for the Java TestCase record this way:

The the builder pattern

is a tad verbose, but it allows us to write test cases with only the fields

that are relevant. The fields that we don't specify will take

their default value, which at the moment is null for all fields.

We'll change it later.

record TestCase(String name,

TodoList model,

String path,

String selector,

List<String> matches) {

@Override

public String toString() {

return name;

}

}

Hand-coding builders is a little tedious, but doable, though there are

automated ways to write them.

Now we can rewrite our Java test cases with the Builder, to

achieve greater clarity:

public static TestCase[] indexTestCases() {

return new TestCase[]{

new TestCase.Builder()

.("all todo items are shown")

.(new TodoList()

.add("Foo")

.add("Bar"))

.("ul.todo-list li")

.("Foo", "Bar")

.build(),

// ... other cases

new TestCase.Builder()

.("highlighted navigation link: Completed")

.("/completed")

.("ul.filters a.selected")

.("Completed")

.build(),

};

}

So, where are we with our tests? At present, they fail for the wrong reason: null-pointer exceptions

due to the missing model and path values.

In order to get our new test cases to fail for the right reason, namely that the template does

not yet have logic to highlight the correct link, we must

provide default values for model and path. In Go, we can do this

in the test method:

func Test_indexTemplate(t *testing.T) {

for _, test := range testCases {

t.Run(test.name, func(t *testing.T) {

buf := renderTemplate(test.model, test.path)

// ... same as before

})

}

}

In Java, we can provide default values in the builder:

public static final class Builder {

String name;

String selector;

List<String> matches;

// ...

}

With these changes, we see that the last two test cases, the ones for the highlighted link Active and Completed fail, for the expected reason that the highlighted link does not change:

=== RUN Test_indexTemplate/highlighted_navigation_link:_Active

index_template_test.go:82:

Error Trace: .../tdd-templates/go/index_template_test.go:82

Error: Not equal:

=== RUN Test_indexTemplate/highlighted_navigation_link:_Completed

index_template_test.go:82:

Error Trace: .../tdd-templates/go/index_template_test.go:82

Error: Not equal:

IndexTemplateTest > testIndexTemplate(TestCase) > [5] highlighted navigation link: Active FAILED

org.opentest4j.AssertionFailedError:

Expecting:

to be equal to:

but was not.

IndexTemplateTest > testIndexTemplate(TestCase) > [6] highlighted navigation link: Completed FAILED

org.opentest4j.AssertionFailedError:

Expecting:

to be equal to:

but was not.

To make the tests pass, we make these changes to the template:

<ul class="filters">

<li>

<a " href="#/">All</a>

</li>

<li>

<a " href="#/active">Active</a>

</li>

<li>

<a " href="#/completed">Completed</a>

</li>

</ul>

Java - jmustache

<ul class="filters">

<li>

<a " href="#/">All</a>

</li>

<li>

<a " href="#/active">Active</a>

</li>

<li>

<a " href="#/completed">Completed</a>

</li>

</ul>

Since the Mustache template language does not allow for equality testing, we must change the data passed to the template so that we execute the equality tests before rendering the template:

private String renderTemplate(String templateName, TodoList model, String path) {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream(templateName)));

var data = Map.of(

"model", model,

);

return template.execute(data);

}

And with these changes, all of our tests now pass.

To recap this section, we made the test code a little bit more complicated, so that the test cases are clearer: this is a very good tradeoff!

Recommend

-

40

40

In ourlast article, we discussed the Web Components specifications (custom elements, shadow DOM, and HTML templates) at a high-level. In this article, and the three to follow, we will put these technologies to the test a...

-

10

10

HTML Templates in Go Submitted by NanoDano on Sat, 04/26/2014 - 19:51

-

6

6

Custom Asciidoctor.js html converter with Nunjucks templates 16 Jun 2019 Many thanks to Github user @Mogztter for showing me this code and pointing me the right directi...

-

7

7

Visual Studio Code>Other>Highlight HTML/SQL templates in F#N...

-

12

12

Python Auto-Format HTML Templates in Django with VSCode Posted by Bernhard Knasmüller Octob...

-

41

41

-

14

14

10 HTML templates for your online projectsCollection of 10 HTML templates for online projects with included images, illustrations and simple permissive license. Built on 6 years experience of template making for business...

-

9

9

-

23

23

Share Share Tweet Share Pin It Free Static HTML Website Templates, 2021 Updated

-

6

6

An easier way to generate PDFs from HTML templates Skip to main content Applications frequently a...

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK