The Hunt For MH370 Goes On With Barnacles As A Lead

source link: https://hackaday.com/2024/04/22/the-hunt-for-mh370-goes-on-with-barnacles-as-a-lead/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

The Hunt For MH370 Goes On With Barnacles As A Lead

On March 8, 2014, Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 vanished. The crash site was never found, nor was the plane. It remains one of the most perplexing aviation mysteries in history. In the years since the crash, investigators have looked into everything from ocean currents to obscure radio phenomena to try and locate the plane. All have thus far failed to find the wreckage.

It was on July 2015 when a flaperon from the aircraft washed up on Réunion Island. It was the first piece of wreckage found, and it was hoped it could provide clues to the airliner’s final resting place. While it’s yet to reveal a final answer as to the aircraft’s fate, some of the ocean life living on it could help investigators need to find the plane. The picture is murky right now, but in an investigation where details are scarce, every little clue helps.

Barnacles

A fragment of engine cowling believed to be from MH370, which washed up in December 2015. Note the barnacles covering the debris. Credit: ATSB

Today, there’s a general consensus that MH370 probably went down somewhere in the Indian Ocean. That’s supported both by analysis of satellite pings and the wreckage which washed up at Réunion. Notable on the wreckage was a small population of barnacles of the species Lepas anatifera.

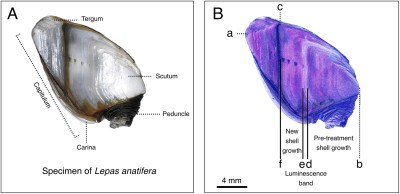

David Griffin, an Australian government scientist, expressed optimism that these barnacles could help pinpoint the crash site. Similarly, American scientist Gregory Herbert thought much the same thing. Akin to the rings of a tree, the shells of the barnacle can reveal a history of the organism. By analyzing the found barnacles against their typical life cycle, they could potentially reveal details about where the wreckage had been.

By studying a barnacle’s shell, it’s possible to reconstruct the conditions of its growth. Credit: research paper

A great deal of research was undertaken to learn more about the species in the hope that better understanding the barnacles could help find the plane. As a species, Lepas anatifera proved to be uniquely perfect for further analysis. These barnacles tend to attach to floating debris, such as that generated by a catastrophic plane crash. Under stable conditions, the barnacles tend to grow at a fairly consistent rate. By looking at the oldest barnacles on the debris, one could try and estimate the length of time it had been in the water. Combining this with models of ocean currents could help figure out where a piece of debris might have come from.

Unfortunately, the innate variability of the sea organisms frustrated easy analysis. By growing their own barnacles in different conditions, researchers soon found that varying sea temperatures had a significant impact on growth size. As did the amount of nutrients available for the barnacles to feed on. Some researchers found that their barnacles maxed out at 20 mm in length after three months, while others grew barnacles over twice as long in a third of the time.

Scientist David Griffin pictured with a replica flaperon used in drift modelling studies by the CSIRO. Source: Peter Mathew via CSIRO

After much analysis and comparison of barnacle studies, initial optimism was dampened by the reality of the evidence. The largest barnacles on the flaperon suggested it had been floating for about four months — far less than the 16 months between the aircraft’s disappearance and the flaperon’s discovery. Indeed, similar results were found for other debris recovered since then, too. “Unfortunately for crash investigators, the new, faster Lepas growth rates suggest that the large (36 mm) Lepas found on the missing Malaysian Airline flight MH370 wreckage at Reunion Island – 16 months after the aircraft was believed to have crashed in 2014 – were much younger than previously realised,” said Iain Suthers, a researcher with the University of New South Wales who worked on barnacle studies.

In testing, it was found the flaperon floated in an orientation where much of it stuck out of the water. And yet, the flaperon was found with barnacles on these very surfaces. It’s a question that doesn’t have an easy answer at this stage. Credit: CSIRO

Other mysteries have presented baffling inconsistencies, too. When French researchers floated the flaperon in a tank to determine how it floated, they found one edge would consistently stick out of the water. This would be all well and good, except this surface was found covered in barnacles, too. This should have been impossible, as the barnacles cannot grow under these conditions.

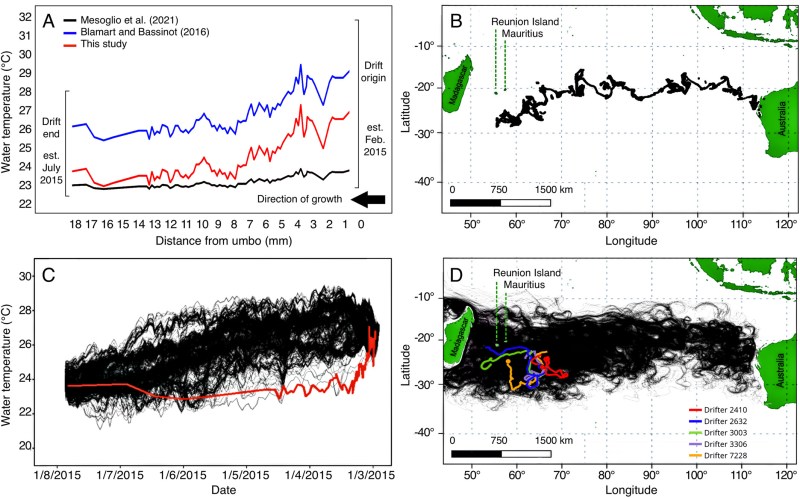

There are still hopes that barnacle analysis could provide new areas for authorities to search for the plane. In concert with his research team, Herbert published a paper late last year positing a new drift path for the flaperon, based on barnacle studies. The paper lays out a deep analysis of a barnacle shell found on the MH370 flaperon debris. The shell’s makeup was used to determine the sea temperatures at different stages of the barnacle’s growth, based on established research into Lepas anatifera. This was then used to generate a reconstruction of the barnacle’s potential drift path through the ocean before it wound up on Réunion Island. The team hoped to repeat their analysis with larger barnacles from the flaperon debris, if they were to be released for analysis by French authorities.

Herbert’s research team used the sea surface temperature history baked into a barnacle’s shell to generate a new partial drift model for debris that washed up on Réunion Island. Credit: research paper

Grasping at (Very Scientific) Straws

It bears noting that these techniques aren’t the typical way that we hunt for crashed airliners. Normally, radar logs, transponder signals, and other data give us enough to go on to know where to look. In the case of MH370, much of that wasn’t available, meaning authorities and scientists had to get far more creative to hunt it down.

There are still some holes in the barnacle analysis as mentioned above. Plus, without access to all the barnacle evidence, researchers are naturally constrained. Ultimately, it’s an odd application of marine biology to try and solve an implacable mystery. It’s valid to try, but there’s no guarantee these small shelled organisms will turn up the plane that has so far proven impossible to find.

The ongoing investigation into MH370’s disappearance highlights the limitations and potential of using marine biology in solving such mysteries. Despite the advanced technologies and the novel application of biological data, significant gaps remain in our understanding of the debris’ drift patterns.

As researchers continue to study these marine organisms, the MH370 mystery underscores a broader truth: the ocean’s sheer size often defies our efforts to understand it. Trying to find a needle in a haystack would be a cinch by comparison.

Featured image: “Grand Canyon Sunset Through a de Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otter Airplane Cockpit” by Nan Palmero.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK