Building a high-performance database buffer pool in Zig using io_uring's new fix...

source link: https://gavinray97.github.io/blog/io-uring-fixed-bufferpool-zig

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Table of Contents

Preface

Credit for OpenGraph images goes to Unixism and the Zig Foundation.

A few days ago, I had a shower thought:

Shower thought:

— Gavin Ray (@GavinRayDev) October 10, 2022

io_uring lets you pre-allocate and register a pool of buffers to use for ops, instead of providing them on each call

Why not implement a DB buffer pool where the bufs are registered w/ io_uring?

Then you don't need to pass buffers between the BP + disk manager pic.twitter.com/LDnlO4EWvp

This post is the result of exploring that thought.

Introduction

io_uring is a new Linux kernel API that allows applications to submit I/O requests to the kernel and receive completion events for those requests. It is a much more efficient alternative to the traditional epoll/kqueue-based asynchronous I/O model. In this post, we will explore how to build a high-performance database buffer pool in Zig using io_uring's new fixed-buffer mode.

I chose Zig to implement this because:

- I'm not very familiar with it, and it was a good opportunity to learn

- It turns out that Zig has a nice

io_uringAPI baked intostd, which makes it a natural fit for this project

Incidentally, the author of said API is the founder of TigerBeetle DB.

DISCLAIMER:

- I am not an expert on Zig, nor

io_uring, nor databases. This is a learning project for me, and I'm sharing it in the hopes that it will be useful to others. - The disk manager & buffer pool implementations in this post do not implement critical sections/locking, so they are not thread-safe.

- They are also incomplete implementations. Only enough to showcase somewhat-realistic use of

io_uring's fixed-buffer mode in a database context was written.

- They are also incomplete implementations. Only enough to showcase somewhat-realistic use of

What is a buffer pool?

A database buffer pool is essentially a cache of database pages (chunks of fixed-size bytes). When a database page is requested, it is first checked if it is already in the buffer pool. If it is, then the page is returned immediately. If it is not, then the page is read from disk and added to the buffer pool. If the buffer pool is full, then a page is evicted from the buffer pool to make room for the new page.

The buffer pool is a critical component of a database. It is responsible for reducing the number of disk reads and writes. It also reduces the amount of memory required to store the database pages. In this post, we will explore how to build a high-performance buffer pool in Zig using io_uring's new fixed-buffer mode.

How are they usually built?

The traditional way to architect a buffer pool is to have it function similar to an arena allocator. A fixed amount of memory is allocated up-front when the buffer pool is created, and when reading/writing pages to disk, pointers/references to fixed-size chunks of that memory are passed to the disk manager. The disk manager then reads/writes the pages to disk, and the buffer pool is responsible for updating the page's metadata (e.g. dirty bit, reference count, etc).

When the disk manager performs I/O operations, these generally block the calling thread. This means that if the buffer pool wants to support concurrent I/O operations, then it must offload them to separate threads. This is usually done by having a thread pool that I/O request can be submitted to.

This architecture is simple and easy to understand, but it has a few drawbacks:

- Page reads/writes are performed synchronously, which means that the buffer pool must wait for the disk manager to complete the I/O operation before it can return the page to the caller.

- There is non-insignificant overhead in spawning OS threads

- The buffer pool has to explicitly pass pointers to the pages to the disk manager, which means that the buffer pool must keep track of the page's location in memory.

Getting io_uring involved

The primary appeal of io_uring is that it allows applications to submit I/O requests to the kernel asynchronously, and receive completion events for those requests. This doesn't make reading/writing pages to disk necessarily faster, but it does increase potential I/O throughput by allowing the buffer pool to submit multiple I/O requests to the kernel at the same time.

One of the more recent features of io_uring is the ability to pre-allocate and register a pool of buffers to use for I/O operations. This means that the buffer pool can pre-allocate a pool of memory, and then register that memory with io_uring. When the buffer pool wants to read/write a page to disk, it can simply pass the index to a buffer in the pool to the disk manager. The disk manager can then perform the I/O operation using that buffer, and the buffer pool will (optionally) receive a completion event when the I/O operation completes.

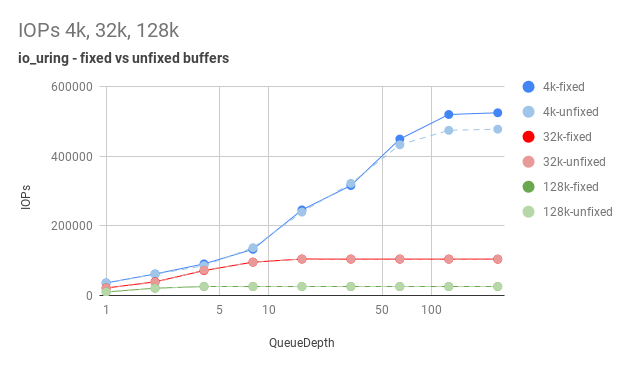

The performance implications of this can be significant. Although experimentally, this appears to be dependent on the queue depth, see:

Graph from the above article, showing the performance of fixed-buffer mode vs standard mode:

It seems reasonable that if you're building a database, and you want it to GO VERY FAST, you probably want to:

- Use

io_uringto perform I/O operations - Pre-register your buffer pool memory with

io_uringusing fixed-buffer mode - Implement a concurrent design model to take advantage of

io_uring's asynchronous nature

As it turns out, some very smart people have recently done this. See the TUM papers on Umbra's design:

That last bit is a topic for another, much longer post. For now, we will focus on the first two points.

Show me the code!

We'll start with the Disk Manager, because you need it first and it's where the io_uring functionality is used.

Disk Manager Implementation

We'll start with some constants to declare a page size and the number of pages in the buffer pool:

const PAGE_SIZE = 4096;

const BUFFER_POOL_NUM_PAGES = 1000;

Next, we'll define a struct to encapsulate the behavior of a disk manager.= We need three things here:

- A

std.fs.Fileto read/write from - An

io_uringring instance, with fixed-buffer mode enabled - The pages/buffers that we will use for I/O operations (to be shared with the buffer pool later)

- An array of

iovecstructs, to hold pointers to the buffer pool pages (these are the "fixed-buffers" that we'll be using)

const std = @import("std");

const IoUringDiskManager = struct {

file: std.fs.File,

io_uring: std.os.linux.IO_Uring,

// iovec array filled with pointers to buffers from the buffer pool.

// These are registered with the io_uring and used for reads and writes.

iovec_buffers: []std.os.iovec,

// ...

};

Next, we'll define a function to initialize the disk manager. This function will:

- Spawn and configure an

io_uringinstance with a queue depth of 1024 to benefit from the fixed-buffer mode - Allocate the

iovecarray, and fill it with pointers to the buffer pool pages - Register the

iovecarray with theio_uringinstance

const IoUringDiskManager = struct {

// ...

const Self = @This();

pub fn init(file: std.fs.File, buffer_pool_buffers: *[BUFFER_POOL_NUM_PAGES][PAGE_SIZE]u8) !Self {

const io_uring_queue_depth = 1024;

const io_uring_setup_flags = 0;

var io_uring = try std.os.linux.IO_Uring.init(io_uring_queue_depth, io_uring_setup_flags);

// register buffers for read/write

var iovec_buffers = try std.heap.page_allocator.alloc(std.os.iovec, BUFFER_POOL_NUM_PAGES);

errdefer std.heap.page_allocator.free(iovec_buffers);

for (buffer_pool_buffers) |*buffer, i| {

iovec_buffers[i] = std.os.iovec{

.iov_base = buffer,

.iov_len = PAGE_SIZE,

};

}

try io_uring.register_buffers(iovec_buffers);

return Self{

.file = file,

.io_uring = io_uring,

.iovec_buffers = iovec_buffers,

};

}

pub fn deinit(self: *Self) void {

self.io_uring.deinit();

self.file.close();

}

};

Finally, we'll define two functions to read and write pages to disk. Breaking down what's going on here:

- The implementation of

read_pageandwrite_pagedelegate to theio_uringfixed-buffer read/write functionality- These queue but do not submit the requests

- We want to retain the ability to submit them ourselves, in case we want to batch, link, or otherwise manipulate the requests

const IoUringDiskManager = struct {

// ...

pub fn read_page(self: *Self, frame_index: usize) !void {

std.debug.print("[IoUringDiskManager] read_page: frame_index={}\n", .{frame_index});

const iovec = &self.iovec_buffers[frame_index];

const userdata = 0x0;

const fd = self.file.handle;

const offset = frame_index * PAGE_SIZE;

const buffer_index: u16 = @intCast(u16, frame_index);

_ = try self.io_uring.read_fixed(userdata, fd, iovec, offset, buffer_index);

_ = try self.io_uring.submit();

}

pub fn write_page(self: *Self, frame_index: usize) !void {

std.debug.print("[IoUringDiskManager] write_page: frame_index={}\n", .{frame_index});

const iovec = &self.iovec_buffers[frame_index];

const userdata = 0x0;

const fd = self.file.handle;

const offset = frame_index * PAGE_SIZE;

const buffer_index: u16 = @intCast(u16, frame_index);

_ = try self.io_uring.write_fixed(userdata, fd, iovec, offset, buffer_index);

_ = try self.io_uring.submit();

}

};

Here's the definition of read_fixed from std/os/linux/io_uring.zig. You can extrapolate this for write_fixed and readv/writev_fixed:

/// Queues (but does not submit) an SQE to perform a IORING_OP_READ_FIXED.

/// The `buffer` provided must be registered with the kernel by calling `register_buffers` first.

/// The `buffer_index` must be the same as its index in the array provided to `register_buffers`.

///

/// Returns a pointer to the SQE so that you can further modify the SQE for advanced use cases.

pub fn read_fixed(

self: *IO_Uring,

user_data: u64,

fd: os.fd_t,

buffer: *os.iovec,

offset: u64,

buffer_index: u16,

) !*linux.io_uring_sqe {

const sqe = try self.get_sqe();

io_uring_prep_read_fixed(sqe, fd, buffer, offset, buffer_index);

sqe.user_data = user_data;

return sqe;

}

To wrap up, we can write a simple test to read and write a page to disk:

test "io_uring disk manager" {

const file = try std.fs.cwd().createFile("test.db", .{ .truncate = true, .read = true });

defer file.close();

// Is this allocation pattern right? I'm not sure, but it passes the tests.

var buffer_pool_buffers = [_][PAGE_SIZE]u8{undefined} ** BUFFER_POOL_NUM_PAGES;

var disk_manager = try IoUringDiskManager.init(file, &buffer_pool_buffers);

const page_id: u32 = 0;

// Modify the page in the buffer pool.

const page = &buffer_pool_buffers[page_id];

page[0] = 0x42;

// Submit the write to the io_uring.

try disk_manager.write_page(page_id);

_ = try disk_manager.io_uring.submit_and_wait(1);

// Read the page from disk (modifies the backing buffer)

try disk_manager.read_page(page_id);

// Wait for the read to complete.

_ = try disk_manager.io_uring.submit_and_wait(1);

// Verify that the page was read correctly.

try std.testing.expectEqualSlices(u8, &[_]u8{0x42}, buffer_pool_buffers[page_id][0..1]);

}

Finally, let's build the buffer pool on top of this.

Buffer Pool Manager Implementation

Our buffer pool manager will hold a few pieces of state:

- A pointer to the disk manager (to read/write pages to disk which are not in memory)

- A pointer to the buffer pool frames, where we'll store our pages

- A mapping from a logical page ID to a physical frame ID (the "page table")

- A list of frame indices which don't have any pages in them/are "free" (the "free list")

pub const IoUringBufferPoolManager = struct {

// Disk Manager is responsible for reading and writing pages to disk.

disk_manager: *IoUringDiskManager,

// Frames is an array of PAGE_SIZE bytes of memory, each representing a page.

frames: *[BUFFER_POOL_NUM_PAGES][PAGE_SIZE]u8,

// Page table is a mapping from page id to frame index in the buffer pool

page_id_to_frame_map: std.AutoHashMap(u32, usize),

// Free list is a list of free frames in the buffer pool

free_list: std.ArrayList(usize),

};

When we initialize a buffer pool manager instance, we want to do two things:

- Initialize the free list and page table. We'll also resize them to

BUFFER_POOL_NUM_PAGESto avoid reallocations. - Add every frame index to the free list. All frames are free at the start.

pub const IoUringBufferPoolManager = struct {

// ...

const Self = @This();

pub fn init(frames: *[BUFFER_POOL_NUM_PAGES][PAGE_SIZE]u8, disk_manager: *IoUringDiskManager) !Self {

var page_map = std.AutoHashMap(u32, usize).init(std.heap.page_allocator);

errdefer page_map.deinit();

var free_list = std.ArrayList(usize).init(std.heap.page_allocator);

errdefer free_list.deinit();

// Statically allocate the memory, prevent resizing/re-allocating.

try page_map.ensureTotalCapacity(BUFFER_POOL_NUM_PAGES);

try free_list.ensureTotalCapacity(BUFFER_POOL_NUM_PAGES);

// All frames are free at the beginning.

for (frames) |_, i| {

try free_list.append(i);

}

return Self{

.disk_manager = disk_manager,

.frames = frames,

.page_id_to_frame_map = page_map,

.free_list = free_list,

};

}

pub fn deinit(self: *Self) void {

self.page_id_to_frame_map.deinit();

self.free_list.deinit();

}

The minimum functionality we need to test our implementation are:

- A

get_pagefunction which will read a page from disk if it's not in memory - A

flush_pagefunction which will write a frame to disk

pub const IoUringBufferPoolManager = struct {

// ...

const Self = @This();

pub fn get_page(self: *Self, page_id: u32) !*[PAGE_SIZE]u8 {

// If the page is already in the buffer pool, return it.

if (self.page_id_to_frame_map.contains(page_id)) {

const frame_index = self.page_id_to_frame_map.get(page_id).?;

return &self.frames[frame_index];

}

// Check if there are any free pages in the buffer pool.

if (self.free_list.items.len == 0) {

// TODO: Evict a page from the buffer pool.

return error.NoFreePages;

}

// If the page is not in the buffer pool, read it from disk.

const frame_index = self.free_list.pop();

try self.disk_manager.read_page(frame_index);

_ = try self.disk_manager.io_uring.submit_and_wait(1);

// Add the page to the page table.

self.page_id_to_frame_map.put(page_id, frame_index) catch unreachable;

// Return the page.

return &self.frames[frame_index];

}

pub fn flush_page(self: *Self, page_id: u32) !void {

if (self.page_id_to_frame_map.contains(page_id)) {

const frame_index = self.page_id_to_frame_map.get(page_id).?;

try self.disk_manager.write_page(frame_index);

_ = try self.disk_manager.io_uring.submit_and_wait(1);

}

}

};

We can now write the grand-finale test to verify that our buffer pool and disk manager work together.

test "io_uring buffer pool manager" {

const file = try std.fs.cwd().createFile("test.db", .{ .truncate = true, .read = true });

defer file.close();

var buffer_pool_buffers = [_][PAGE_SIZE]u8{undefined} ** BUFFER_POOL_NUM_PAGES;

var disk_manager = try IoUringDiskManager.init(file, &buffer_pool_buffers);

var buffer_pool_manager = try IoUringBufferPoolManager.init(&buffer_pool_buffers, &disk_manager);

const page_id: u32 = 0;

// We expect the page to be read into frame 999, since we have 1k frames and use .pop() to get the next free frame.

const expected_frame_index = 999;

// Modify the page in the buffer pool (page=0, frame=999).

var page = try buffer_pool_manager.get_page(page_id);

page[0] = 0x42;

// Flush the page to disk.

try buffer_pool_manager.flush_page(page_id);

_ = try disk_manager.io_uring.submit_and_wait(1);

// Read the page from disk (frame=999).

try disk_manager.read_page(expected_frame_index);

// Wait for the read to complete.

_ = try disk_manager.io_uring.submit_and_wait(1);

// Verify that the page was read correctly.

const updated_frame_buffer = &buffer_pool_buffers[expected_frame_index];

try std.testing.expectEqualSlices(u8, &[_]u8{0x42}, updated_frame_buffer[0..1]);

}

Conclusion

If you've gotten this far, thank you for reading! I hope you enjoyed this post and learned something new. I'm bullish on the future of io_uring and its increasing use in popular software. I'm excited to see what comes next, and hopefully now you are too!

This post is the first in what (I intend to be) several on io_uring, specifically around real-world use cases and performance. If you have any questions or comments, please feel free to reach out to me on Twitter or via email. I'd love to hear from you!

If this post contains errors, mistakes, misinformation, or poor-practices, please bring them to attention. I'd be surprised if there weren't any.

References

Thanks & Appreciation

I'd like to thank the following people for their help and feedback on this post:

- Phil Eaton, for reviewing the draft and providing feedback.

- The Zig Discord community, for answering many questions. I owe them a great debt.

- Ilya Korennoy for taking the time to field my io_uring questions.

Recommend

-

55

55

当前 Linux 对文件的操作有很多种方式,最古老的最基本就是 read 和 write 这样的原始接口,这样的接口简洁直观,但是真的是足够原始,效率什么自然不是第一要素,当然为了符合 POSIX 标准,我们需要它。一段...

-

74

74

Linux 5.1合入了一个新的异步IO框架和实现:io_uring,由block IO大神Jens Axboe开发。这对当前异步IO领域无疑是一个喜大普奔的消息,这意味着,Linux native aio的时代即将成为过去,io_uring的时代即将开启。 从Linux IO说起

-

27

27

Mental experiments with io_uring Recently, a new Linux kernel interface, called io_uring , appeared. I have been looking into it a little bit and I can’t help but wondering about i...

-

25

25

Last fall I was working on a library to make a safe API for driving futures on top of an an io-uring instance. Though I released bindings to liburing called iou , the fut...

-

23

23

Inmy previous post, I discussed the new io-uring interface for Linux, and how to create a safe API for using io-uring from Rust. In the time since that post, I have implemented a prototype of such an API. The crate is cal...

-

31

31

前言 熟悉Linux网络或者存储编程的开发人员,对于libaio [1] (Linux-native asynchronous I/O) 应该并不太陌生。Libaio提供了一套不同于POSIX接口的异步I/O接口,其目的是更加高效的利用I/O设备。在最近几年的过程中...

-

35

35

Sep 21, 2020 • 费曼 io_uring,高并发网络编程新利器 传统高性能网络编程通常是基于select, epoll, kequeue等机制实现,网络上有非常多的资料介绍基于这几种接口的编程模型,尤其是epoll,nginx, redis等都基于其构建,稳定高效,但随...

-

16

16

Aug 2, 2020 • 齐江 下一代异步 IO io_uring 技术解密 Alibaba Cloud Linux 2 是阿里云操作系统团队基于开源 Linux 4.19 LTS 版本打造的一款针对云应用场景的下一代 Linux OS 发行版。在首次推出一年后,阿里云操作系统团队对外正式发布...

-

7

7

#AzureCosmosDB #Database #NoSQLNoSQL Database for High Performance & Scalability | How to Get Started with...

-

6

6

proxy.c « examples index : liburing

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK