Exploring various research methods for building products

source link: https://uxplanet.org/exploring-various-research-methods-for-building-products-99064fed6cfd

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Exploring various research methods for building products

Photo by UX Indonesia on Unsplash

Research is built into the design thinking process.

We conduct research at the start of a project, to learn more about the people we design for and what their goals and frustrations are. We research in the middle of a project, looking to competitors to learn more about existing solutions to peoples’ needs. We even research at the end of a project, hoping to understand whether our solution to peoples’ problems works, and how we need to iterate for the future.

Research is all about understanding. We gather knowledge and feedback, so that we can better define our problem to solve, then determine if our solution solves it.

Albert Einstein said it best:

Photo by Andrew George on Unsplash

“If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spent 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.”

Thinking about the problem starts from a strong place of research — having enough data to create an informed opinion on how to proceed forward.

What type of research can we conduct? How does that research benefit our process? As it applies to design thinking, the research we want to perform can be broken down into four categories.

Behavioral vs. Attitudinal

We can approach our research from a user-centric perspective. We can think about the behaviors of our users, such as what they do in a situation. Perhaps we could create a prototype for a design, then give that prototype to people and watch where they click around the interface. This would be behavioral research, in that we would observe people’s behaviors as they took actions in an experience.

Alternatively, we could think about the opinions of our users, such as, what they think or feel about a situation. Perhaps we use that same prototype, but instead of watching people click around the interface, we ask them about their opinions of that interface. Is it intuitive? Does it solve their problems? Would it help them with their goals? This would be attitudinal research, in that we would observe what people say as they were asked questions about an experience.

Christian Rohrer of the Nielsen Norman Group has written a great analysis of how to think about different types of research methods. Here, I’ll break down what he’s written about research and apply it to how we can think about empathizing with our users.

If we map behavioral and attitudinal characteristics of research in a matrix, we’d get something like this:

The first axis of research methods — what people do vs what people say.

On one side of this axis, we have behavioral types of research, based on what people DO. On the other, we have attitudinal types of research, based on what people SAY.

An example of behavioral research would be something like eye tracking, where a user’s eye movements are monitored as they look at an interface. This type of research has produced the F-pattern and Z-pattern for the web, for example.

An example of attitudinal research would be something like a user interview, where a researcher talks to users to understand more about their goals, wants, and needs. This type of research has produced design artifacts like personas, where we are able to have a better understanding of the people we design for.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative

We can also approach our research strategy from a feedback perspective. Are we obtaining our information about our users directly, by having a conversation with them? Or are we obtaining it indirectly, by having them fill out a survey?

If we map those characteristics to a matrix, we’d get something like this:

The second axis of research methods — the why and the how vs. the frequency and magnitude.

On one side of this axis, we have direct research methods, which are qualitative and based on a WHY. On the other side, we have indirect research methods, which are quantitative and based on a QUANTITY.

An example of qualitative research would be something like a focus group, where we bring in several users to discuss a problem and work with them to understand why that problem exists and how to fix it. Focus groups are less common in product design, but could still occur in the context of branding, for example.

An example of quantitative research would be something like an unmoderated UX study, where participants try to complete tasks in a UI without any direction or guidance. We gain quantitative data from this research method, learning how many users are able to complete a task, or how much time it takes to complete that task without any guidance.

The User Research Landscape

If we combine these two axes, we get the following matrix:

Both axes combined.

Using this matrix, we can map out all the different types of user research for us to consider.

Research methodologies mapped to our axes.

This is a comprehensive list of the different types of research available to us as designers. Based on this matrix, we can start to think about how we want to conduct our research.

Do we need to talk to users via an interview? Then we want some direct contact with those users and attitudinal questions to ask them. What are their goals when they come to our product? What are some of the pain points when using our product? How do they currently solve their problems? We can start to structure our research approach depending on the type of research we choose to conduct.

Conversely, we can use this matrix to think about the type of data we want to know. Are we curious about click through rates in our product? Well, we need to know how many people are able to complete a task on our website, and how much time it takes for them to do so. We can go to the matrix, see that we want quantitative, behavioral information, and from there choose a method like clickstream analysis.

Now that we have a sense of the types of research we can conduct, and what categories they fall under, let’s take a look at the times in which we’ll want to use these methods.

Stages of design research

Depending on where you are in your projects (and your research budget), you will want to conduct different types of research. You can think of research before you begin to design, after you have created some designs, and after your designs have been released.

Background research

The purpose of background research is to align what we want to make with what users want to use. Our goal is to build a picture of our users while also understanding any solutions that currently exist to their problems. Here, we have several methods we can use to get a better understanding of these things.

Surveys

Surveys are a great way to get a lot of information about users with a small amount of time invested. You can create a form with a few questions you want answers to, and send out that form to a lot of participants to generate qualitative and quantitative information. Additionally, you can create screener surveys, which function as a filter for finding users you really want to talk to.

Interviews

Photo by UX Indonesia on Unsplash

Once you’ve identified a few users you want to talk to, you can schedule conversations with them. User interviews are excellent at giving you the opportunity to directly ask questions and better understand people’s motivations. You can go into detailed conversations to understand what they need, and dive deeper into those needs by asking “why” directly.

Competitive analysis

A competitive analysis I conducted while working on a new feature.

In addition to understanding your users, it’s crucial to understand the products that exist in the marketplace. Are there other businesses that have solved this problem already? What can you do to solve the problem differently? Are there common conventions in your industry that you need to be aware of as a designer, such as, the way users are used to seeing content? By understanding the competition, you can get a sense of what works, what doesn’t, and how you can improve it.

Once we have a good understanding of our users and competitors, we would move on in the design thinking process. We’d define the problem to solve, ideate possibilities, and eventually design solutions. When those solutions are ready to be shown to users, we’d conduct usability research.

Usability research

https://unsplash.com/photos/5QiGvmyJTsc

The purpose of usability research is to validate our assumptions and make sure our designs work. Can users use what we made? Does it make sense, and is it intuitive? Or does it fail? That’s OK too — we haven’t launched it yet. We need to know what works and what doesn’t, so we can improve our designs and release them.

This works with anything we’ve made: sketches, wireframes, prototypes, live apps, or even websites. We can conduct usability research in the earlier steps of the design thinking process, for example, with competitor products to see the usability issues in those products. Or we can conduct usability research on our existing product, in order to learn how we can enhance it.

We can also revisit conversations with users we spoke to during our background research. A user we interviewed at the start of our project could come back to test our designs, and we could ask them how well we succeeded.

Once our usability research is complete, we can move on in the process. We would finish our designs, build them with developers, then watch as users start to adopt our product. After some product usage, we could conduct research to see how our product is doing.

ROI research

The purpose of ROI research, or “Return on Investment” research, is to see the performance of our product. How is what we made doing? How is it performing in terms of its design, usability, sales, revenue, conversion, or engagement?

There are several methods that are very informative for this type of research:

Analytics

Photo by Stephen Phillips - Hostreviews.co.uk on Unsplash

Analytics allow us to gain a large amount of quantitative data about how things are performing. You could observe your SEO, or search engine optimization, to understand how many people come to your website, and how often. It’s behavioral instead of attitudinal, however, so you won’t understand why, necessarily.

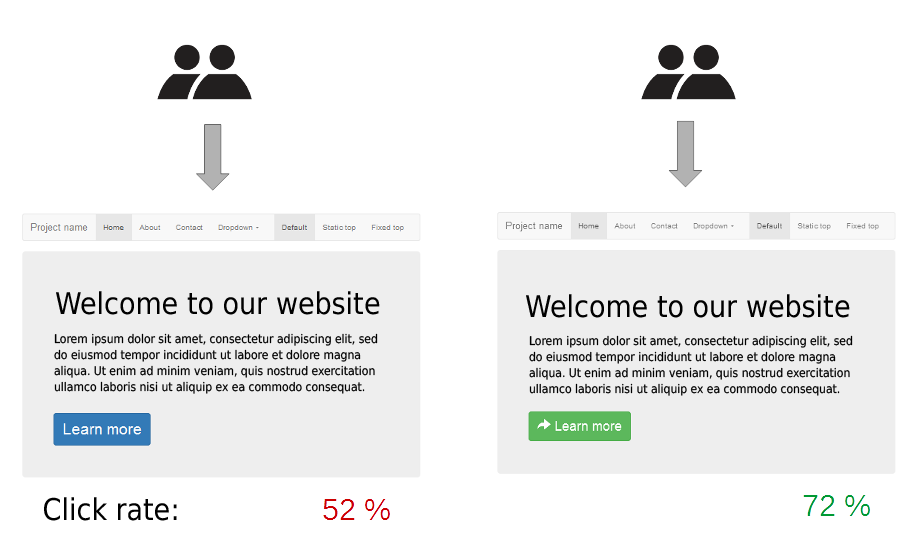

A/B Testing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A/B_testing

You could also conduct A/B testing in your product. What is it like to change a word, or a color? To move an image from the left side of the screen to the right? This type of testing is quite granular and happens with more mature products looking to optimize their designs. Google is famous for an extreme example of this type of testing, where they tested 41 different shades of blue in order to determine the optimal color to incentivize engagement.

User engagement scores

A more attitudinal research method for understanding the performance of your product is to ask users how they feel after using it. One way to do so is by using CSAT scores, or a customer satisfaction score. This method asks users to rate if their expectations have been met after using the product. We can take those ratings and average them in order to determine how satisfied our users are after using a product.

Since we are in the first stage of the design thinking process, we’ll want to conduct background research. That means we’ll need to understand who our users are, and what currently exists to help them.

Research is an ongoing process

User research can happen at any stage in your product’s lifecycle. You may need to understand more about the problem you’re trying to solve — if so, conduct Background research. If you’re wondering whether or not people can use your solution, conduct Usability research. If you’re more curious about how your product is performing, conduct ROI research.

Truthfully, you should be doing all three of these types of research for your products. Learning more about our users, and how we can help them with their goals, is an ongoing process that allows us to make the best solutions we can for the people we design for.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK