Towards the HyperNormal—living in an increasingly fake world

source link: https://uxdesign.cc/towards-the-hypernormal-6debcd3c234d

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Towards the HyperNormal—living in an increasingly fake world

Recent series of drawings (The drawings shown are real, hand-drawn on paper. The frame and book mock-up images are fake, made digitally, to reinforce the thesis of the text.)

Vividly imagining while pragmatically producing

Lately I’ve been thinking about creative vision. How does it operate in propelling one purposely forward? If it is lacking, might it hold one back aimlessly? Visionaries from the art world continuously work on exploring new terrain within their work, challenging everything: the social norms of the day, the structures of political-economic-state power, the current culture, media, hegemonic structures, one’s past work, one’s present work… It is important to be continuously working toward something, moving forward and advancing one’s output. As a beloved studio instructor once offered during my time learning creative practice in undergrad studies, “By the time that society accepts proposed ideas, visual languages, behaviours, processes, and sensibilities, the creative makers of those once-speculative propositions have long moved on to explore other interests and ambitions.” While it is debatable that the Thatcher-Reagan ‘trickle-down effect’ actually functions in the sphere of economics for real people, trickle-down culture is a certainty. It is revealed in the everyday, energetically at work in design, art, and commerce. It is self-evident to point out that by the time large, risk-averse international brands have adopted once progressive ideas circulating in social and cultural spheres, smaller and more nimble companies have progressed on to new ideas. The signifiers adopted by the large, slow moving less vibrant companies will have lost their relevancy and bite.

I would argue that for the majority — risk-averse in the decisions that have shaped their lives — the ultra new is out of view, most likely out of perception. “Early-adoption” practices are embraced by the limited few, the insiders, and the seekers — at least from a creative perspective.

Most companies and the individuals employed therein are more confident adopting ideas after they have been tested, embraced, and approved by those with cultural knowledge after becoming familiar with the majority. A comfort level is associated with the understood. There is a reason why institutions vibrant and curious in charting new ground look, feel, and function differently.

And so I’ve been obsessing about this concept of “vision” and what it actually means to have one that consistently propels one forward in a healthy, sustainable manner toward an ever better, fulfilling future. I’ve been thinking about what the considerations are for articulating a vision, how an individual or organization stays on track in pursuit of one, and perhaps what may be some of the necessary tools, strategies, and conceptual frameworks for preventing a vision formed out of good intentions from being corrupted. I am convinced that we have all devoted much time and energy towards ethical, questionable, and even toxic forms of pursuit. I am interested in exploring what some of the influencing motivations might be for deciding to follow a particular vision. How are these visions framed? How are they defended? What effect might they have on us as individuals caught up in the forces of culture, influence, and authority surrounding us?

We live in a strange world

I think it is safe to say that we are experiencing a moment when most (if not all) of our historically-cherished institutions are undergoing a period of questioning. This critique of our political institutions, our education system, our state-managed policing forces, the financial systems, news and media organizations, and medical apparatus are bumping up against skepticism and distrust that feels significant.

There are precedents. These behaviours have been historically documented under different conditions with different articulations. This doesn’t reduce the significance of what we are currently experiencing, but it does highlight the fact that in other countries, cultures, political systems, and eras, the lack of vision exhibited by the predominant governing institutions and forces of power have typically lead to social instability, retreat, and distrust. We are currently experiencing a new form of this suspicion, shaped according to the specific issues of our own distinct time and social conditions.

For documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis, in his explorations of power in all of its forms, he has seen this all before. In his 2016 release of HyperNormalisation, his interest resides in the crucial factors that have led to the strange conditions of contemporary instability, and the tenuous points of contact with historical analogies. In his research, imbalance forms a core thread extending into our present circumstances.

“Extraordinary events keep happening that undermine the stability of our world. Yet those in control seem unable to deal with it, and no one has any vision of a different or a better kind of future.”[1] —Adam Curtis

Within the documentary, the historical example that most clearly defines the hyper-normal condition is what was happening prior to the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union. Within that society there was the expression of an all-pervading narrative of something that was not real. A blatant, unhidden party line persisted that the state of the economy was on track, and that living conditions were improving. And because it was hegemonic in structure, many went along with the fantasy that propped up the fake system, choosing to play along because it was impossible to see beyond what existed. But there was a problem: the everyday conditions that were obvious and present in everyone’s lives were explicit and revealed right before them, out in the open.

“The Soviet Union became a society that knew that what their leaders said was not real, because they could see with their own eyes that the economy was falling apart. But everybody had to play along and pretend that it was real, because no one could imaging any alternative. This in essence is HyperNormalisation. You were so much a part of the system that it was impossible to see beyond it. The fake-ness was hyper normal.”[2] — Adam Curtis

Book cover

The leaders of the Soviet Union were able to impose an ongoing masquerade until cracks began to show up in the everyday lives of the population. Empty grocery store shelves, rampant corruption, inactive leaders paralyzed and unable to act because they had no understanding of how to fix the system or make recommendations. Eventual collapse followed, and we all know where the story proceeds from here. This lack of vision — or at best poorly constructed and articulated vision — is of interest for me. I have experienced institutional decay within my own practice, witnessing how weakened, disrupted, and crippled creative abilities within companies prevented good work and an inability to function rationally. I have witnessed the hollowing out of creative institutions resulting from the redirection of resources (funding, support, ongoing education) from teaching staff into the bureaucracy of administrative offices. I have experienced uncreative and inexperienced personnel hired into leadership positions that have adversely affected the workflow, craft, and creative capacities of teams and whole companies. I have directly observed highly skilled and exceptionally educated individuals fired and removed from faculties on a systematic, regular cycle that seemed routine, absent of any clear reasoning behind the decisions. That being said, I have also worked for incredible, creative companies and institutions that were fulfilling and challenging, eventually leading to exceptional work being made. However, the positive results obtained from these workplaces are somewhat overshadowed in the damage incurred from toxic workplaces. I cannot help but to think that vision — or to be more clear the lack of vision — resulting from unsuitable conditions is the most menacing and disruptive fallouts within the journey creative practitioners take, and that it will affect them more powerfully than anything else. I have experienced a failure of leadership on a number of occasions, and from what I have observed, there is a very real lack of creative ability, creative decision-making, and creative vision from those we are (for the time being) forced to call our managers.

Book spread

Managed outcomes

Where despotic and totalitarian leaders are much more able to lead through the brute coercion of (let’s call them) “hard” tactics, in democratic societies, while the outcomes may be the same, the means are different. Coercion is established through different strategies, what Noam Chomsky would call “the manufacture of consent” through his research into news media. A comparison is often made to the concept of “thought control”, psychological warfare conducted by governments within a democratic society as concealment tactics. When he was writing about the coercive powers of the press, his perspective was more nuanced than today’s meaningless outing of journalists as “liars” and “fake news”. I want to be clear — Chomsky’s thoroughly researched, critical, nuanced reflections upon the media of his day compellingly overshadows the contemporary hollow, vapid, unfounded, and uneducated charges towards today’s media who by the way, produce crucial investigation and reflection upon the issues of our contemporary world. His concerns lay in how the news institutions managed perception through what he termed “agenda-setting” issues — how news was shaped, how the kinds of opinions were controlled, and the type of sources to which the news media referred. [3] The media bias that he was exploring was directly influenced by what the particular news agencies decided to publish, what not to publish, and how much coverage issues were given. Advertising did mould which issues were “fit for print” based on the corporate interests buying advert space, however Chomsky directed his critique more towards the manufacture of consent through the amount of coverage articles received. Much of his argument centred around real world examples of the time where comparisons could be established. For instance, he compared two distinct conflicts being reported on, both in the international press and in the New York Times, based on the word count of each article. He revealed that the NYT coverage of the widening Vietnam war into neighbouring Cambodia received far more coverage than the state-led genocide in East Timor — both of which were occurring concurrently. The experiments that he conducted revealed the media bias towards certain issues expressed through the line lengths of coverage from each story. These line lengths, which he printed and laid out on a gymnasium floor to showcase the imbalance of content detail, revealed the startling discrepancy in coverage. By using a “propaganda model” as he referred to it, it was revealed that this discrepancy was systematically-structured, nuanced to each media agencies’ alliance and particular bias. While still very relevant, I wonder if the issues of media bias facing journalism during the late 70’s and 80’s might seem rather negligible to him in our current media environment given today’s political climate facing news agencies and their work.

Book spread featuring new series of ten drawings

So while news agencies were managing the perception of the western world through the media landscape, other plans were in development by powerful corporations and the financial institutions. The financial sector, realizing that it held increasingly more power in the day-to-day operations of cities, lending practices due to fractional reserve banking policies [4], and an ever-expanding window into their clients’ financial holdings resulting from the digital harvesting of personal information, began to construct an invisible infrastructure beyond anyone’s awareness.

“By the middle of the 1980’s the banks were rising up and becoming ever more powerful in America. What had started ten years before in New York — the idea that the financial system could run society — was spreading. But unlike older systems of power, it was mostly invisible. The writer William Gibson had noticed how the banks and the new corporations were beginning to link themselves together through computer systems. What they were creating was a series of giant networks of information that were invisible to ordinary people and politicians, but those networks gave corporations extraordinary new powers of control.”[5] — Adam Curtis

Giant computer systems presented a business initiative where the operating principle was to make the future predictable. The company Blackrock had poured considerable investment into a system they named “Aladdin”. The goal of the computer was to predict with certainty the levels of risk within any investment made through stock exchanges, derivatives, bank-packaged investment vehicles, futures indexes, real estate deals, corporate mergers, etc. The computer system ran constantly, monitoring the political, economic, social, cultural nooks and crannies of the world, comparing present events with those of the past fifty years. “Not just financial, but all kinds of events. Out of the millions and millions of correlations, the computer spots possible disasters, possible dangers lying in the future, moves the investments to avoid any radical change, and to keep the system stable.” [6]

Book spread featuring Drawing №1

Aladdin greatly contributed to the financial outcomes of the banking and investment sectors of today, amounting to over $15 trillion through the assets it manages. These management systems operated by computers, data bases, computational and detection software have helped to position the financial sector as one of the foremost influential industries on the planet. Through the strategic allocation of capital and the ability to predict market downturn, the financial industry has been able to convince us that it has all of the answers for our future well being. The computer manages this opaque and complex world of transaction, making microsecond decisions. It works away out of view, humming on autopilot. It leaves me wondering, however, if that is a compelling enough vision worth following. Does it create the conditions for creative, more compelling spaces to move forward into? Is it healthy for the future survival of civilization?

All of this, of course, relies on the global markets to expand and grow. Through the manufacture of goods and services that are exchanged for money (a fiat currency), profit powers the global economy and stock exchanges that economists measure through GDP. The exchanging of capital from one party to another relies on both need and desire. Human needs are simple enough to identify: the sale of healthy food really doesn’t require sexy, glossy ad campaigns. The sale of luxury goods, unnecessary products of want, or expensive services offering little more than convenience, however, will usually require some extra convincing. Enter the advertising and marketing industries. The reach of these industries has grown to affect and influence everything that we can conceive of being bought and sold, as well as everything we cannot. New markets are created every day, many of which are largely unregulated due to the incredible speed by which tech moves, leaving any semblance of legal framing playing catch-up. Unregulated markets, as Paul Mason explains in his Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future, is a boon to forms of capitalism with the gloves off.

“Neoliberalism is the doctrine of uncontrolled markets: it says that the best route to prosperity is individuals pursuing their own self-interest, and the market is the only way to express that self-interest. It says the state should be small (except for its riot squads and secret police); that financial speculation is good; that inequality is good; that the natural state of humankind is to be a bunch of ruthless individuals, competing with each other.”[7] — Paul Mason

Book spread featuring Drawing №2

The dizzying capacity of goods, services, and influence being sold is frightening, a kind of ruthlessness enacted through market mechanisms. The question might arise around how this constant energy is maintained. Chomsky has some intriguing things to say on this point. He coherently articulates the goal of contemporary commerce in a highly competitive, global market economy where the reach of marketing and advertising pervades into every realm of human daily activity.

“The goal for the corporations is to maximize profit and market share, and they also have a goal for their target — mainly the population. Now they have to be turned into completely mindless consumers of goods that they do not want. You have to develop what are called ‘created wants’… You have to impose onto people what’s called a ‘philosophy of futility’. You have to focus them on the insignificant things of life like fashionable consumption. How many created wants can I satisfy? We have huge industries — the public relations industry is a monstrous industry — advertising and so on, which are designed from infancy to mould people into this desired pattern.” [8] — Noam Chomsky

Advertising is a story, created around psychological triggers and fantasy that projects the image of a happier, cooler, more successful future version of oneself. These stories have a number of goals: to create wants, influence audiences to ignore their personal instincts, and establish the means of problem-solving through purchasing power. The things that require advertising are the things marketing specialists know we intrinsically don’t need or want. Advertising is the process of moulding perception and creating fictitious desire. Fake feelings, because the desire created by these stories prior to a purchase quickly disappear after the acquisition. This is a short-lived type of vision.

Book spread featuring close-up of Drawing №8

Social unrest

A few decades later after the advent of a public internet and personal computers, we experience the rise of social media. Looking back it was a tsunami of proportions. It managed to seduce us, provoke us all to take part, and while secretly running in the background play a strategically-asymmetric game. On the surface, these new tools gifted us all with the means to stay in touch with friends (and make new virtual ones), search for information online, share our creative exploits with like-minded social groups, and post breaking news and events. All of this was graciously bestowed upon us for free! Shoshana Zuboff, in her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (which has been referred to as the 21-century’s Das Capital for the digital world) eloquently lays out the hidden, surreptitious manner in which today’s digital tycoons have managed to trick us all. From an interview with Russell Brand Zuboff clearly articulates how tech founders, just as the financial institutions decades ago, have managed to build powerful, hidden, invisible infrastructures of corporate power:

“A fellow named Douglas Edwards who was Google’s first brand manager, in his book he has this recollection of Larry Page stating this for the first time, and the question… they’re sitting around the table and they’re saying, ‘Well what business is Google in? Like, how do we even describe Google to the world?’ And Larry Page — who with one of Google’s founders Sergey Brin — Larry Page ruminates on this question and he says (this is 2001), ‘If we did have a category, — a business category — it would be ‘personal information’. Because everything that you do, everything that you say, everywhere that you go, every place that you’ve been, every aspect of your experience is going to be searchable, indexable. We will be able to know it all. And at that moment it became clear that while Google was marketing itself as a search engine — and we thought that we searched Google, even as early as 2001 — those young men understood that they had to reverse the entire process. That it was not users searching Google, it was Google searching users. The search engine worked in reverse. And that was the source of the breakthrough insight that founded surveillance capitalism, because they understood right from the start that they could not do this in a way that people would be aware of. That it had to be hidden. Because users would not allow themselves to be searched, and law-makers would be triggered into passing privacy laws. Right from the start they had something called ‘the hiding strategy’.”[9] — Shoshana Zuboff

Social media is not a creative engine. It does not promote nor does it activate creativity. If anything it limits it, based on the confines of its particular system structures. Everyone’s posted image appears at the same size, in the same proportions, in the same grid. Everyone’s posted text is formatted to the system, so that the insight of a visionary Nobel prize winning scientist will appear exactly the same as a post from a conspiracy theory believer. These might be the most pernicious effects from a technology favouring the management of its users’ content over the promotion of creativity. “Look at modern social media: it manages to allow you to feel that you are totally yourself expressing yourself online, typing it angrily, or beautifully, or whatever you want to do, out into the internet about what you feel all of the time. Yet at the same time, what you are is a component in a series of very complex circuits that is looking at you doing that and saying, ‘Hold on — if he is doing that, then he’s very much like these people over here which we’ve categorized like that.’ And we can say back to that person in the circuit, ‘Oh, if you’re doing that, would you like this as well?’ And you go, ‘Oh, all right!’ Because it’s a bit like you’ve just done, and it makes you sort of feel secure within your individuality. So what they’ve managed to do increasingly in modern systems of management is to accept your individualism and your expressiveness, allow you to feel that you are being more and more expressive, while at the same time managing you quietly and happily so you become part of a very large group that you don’t see because you’re just a little component in the circuit. But the computers look at you and go, ‘Oh there’s about 300 million of those sort of types — we’ll put them in that group.’ It’s not a conspiracy. It’s not a group of people saying ‘Oh, we’ll do this…’. It’s a system that can see from the information that it’s reading from you and lots of other people, the patterns that you are part of and saying, ‘Well, we’ll fit them into that pattern.’ […] If you talk to the tech utopians from Silicon Valley, they will tell you that this is incredibly efficient, and they’re right. It’s an incredibly efficient way of managing the problem that politicians can’t manage, which is our individuality, and our desire to be self-expressive. Its problem is that it is fundamentally conservative, because it’s feeding back to you more of what you like.” [10]

Book spread featuring Drawings №5 and №6

The technology around which social media functions is clearly more adroit at delivering feedback to companies than ever before. Never was it certain regarding how many automobile drivers had read the headline on a billboard strategically placed next to a freeway. It was much more difficult to gauge the success of magazine adverts, television spots, or marketing ephemera placed through mail slots into homes to deliver custom tailored messages. With today’s social media, click rates provide instant feedback on audience interest and response. Logged is the time spent reading an article to how many times an audience member returned to a web page. Everything is recorded, regardless the type of interaction. This information to business is gold. The engineering model is based on feedback, and what loops around gives insight into what is successfully landing. The model integrated into social media works on the same basis. What worked before should work again. ‘If you liked that, you’ll love this.’ If previous actions determine what future choices are presented to us, I wonder at our abilities to make better future versions of ourselves in a world where the range of choices continues to thin out based on precedent. Or beyond that, what the chances are for our current political and economic forms of organization. Democracy has been stressed with the advent of social media. Markets that have functioned in conditions with relative stability are now acting sporadically. “If we consider not just infotech but food production, birth control or global health, the past twenty-five years have probably seen the greatest upsurge in human capability ever. But the technologies we’ve created are not compatible with capitalism — not in its present form and maybe not in any form. Once capitalism can no longer adapt to technological change, post-capitalism becomes necessary. When behaviours and organizations adapted to exploiting technological change appear spontaneously, post-capitalism becomes possible.” [11]

“Everything comes down to the struggle between the network and the hierarchy, between old forms of society moulded around capitalism and new forms of society that prefigure what comes next.” [12] — Paul Mason

Book spread featuring Drawing №7

In the machine

We have all read the recent LaMDA article, published by The Washington Post, leaked from a Google engineer convinced that the tech company’s artificially intelligent chatbot project had become sentient. [13] Perhaps these technologies reflect the extent to which our acceptance of management systems in current and future landscapes of commerce are permissible. To my mind, the concept of AI in all of its farcically-unnatural dimensions not only explicitly lays bare its fake-ness through its description (it is artificial after all), but candidly it leverages the exchanges of everyday human beings online as its feeding ground to copy, obtain ownership, plagiarize, and regurgitate back in the form of responsive ‘language’ within specific computer-to-human contexts. Where power had once strived to hide the computer and machine tech that was organizing and powering the decisions of people, AI does the exact opposite. In fact, it does it in such a way as to skin the software in an ever-so-close human skin. Familiar, but fake. And now it is no longer constrained to particular industries: these systems of management are opening up to our 24-hour personal, professional, and social lives. The aim, as with all neoliberal capitalist initiatives, is to obtain market dominance. Capitalism was built around competition and multiplicity, leading to the Neoliberal monopolies we see surrounding us: think search engine developers, social media empires, personal computer software manufacturers — all complete or near monopolies. The hesitation and distrust expressed towards these technologies is warranted. Similar to the high tech infrastructures that were manufactured silently by financial and social media industries, the plans for AI-enabled tech seem familiarly hushed and blurred out. Criticality and skepticism is good — being unsettled by this stuff is not paranoia. Literacy focused on the physical tech and its usage can only empower audiences into creating healthy relationships with these products and their adoption.

There is a reason why undergrad students are encouraged to obtain a masters degree at a different institution than their undergrad, and why PhD hopefuls are encouraged to look elsewhere as well. This model of putting oneself into situations where different ideas circulate, where different processes of making are encouraged, and where new social connections can be found all aid in building a wider intellectual arena for exploration. The realm of knowledge production has long maintained this model of provoking curiosity and experimentation. I’m not convinced that social media is doing any of that. A vision whereby individuals are strengthened through the layering on of new ideas for challenging perspectives, reflecting upon life, and responding to the world in new ways feels healthy. Daunting. A lot of hard work. But in the long run, a healthy sense of exploration reinforced through a variegated series of challenges will support the intellectually-curious to endure and succeed.

Book spread featuring Drawing №8 and close-up of Drawing №9

In order to respond in healthy ways to toxic influences that would seek to manipulate us, it seems to me that media literacy, criticality, and creativity are crucial abilities to possess in our current atmosphere of media, political, social, and environmental breakdown. Hidden forces have surely always existed, operating the levers of power for agendas and outcomes determined by those who seek control. In today’s world that seems so strange, the tools that are being created are more powerful than ever. My vision is to use them wisely.

Postscript

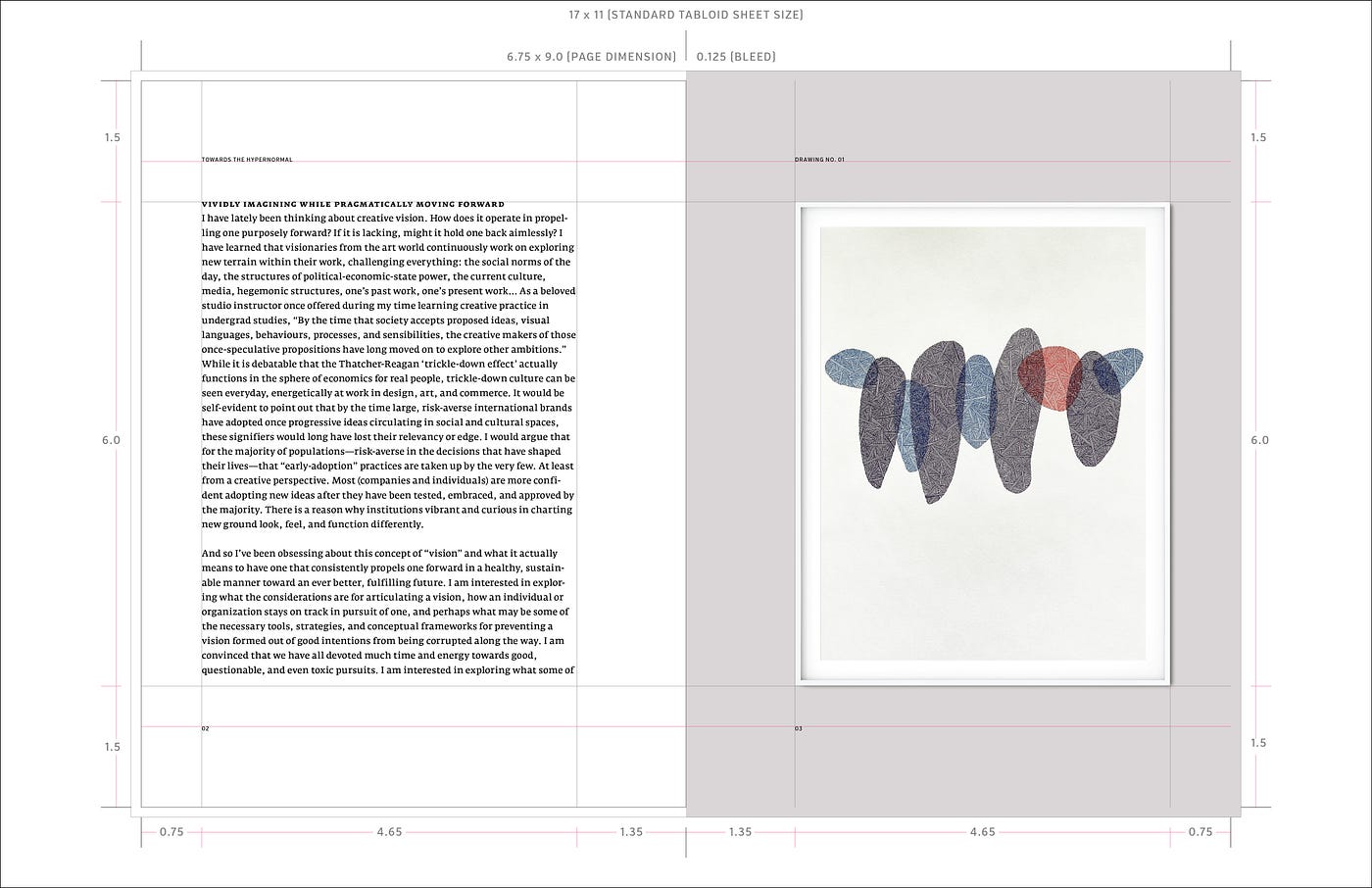

Much of this body of work and essay developed after odd experiments were made on each component. I’ve been interested in making visual work in conjunction with a written text due to the intriguing things that happen when these types of output respond to each other. The dialectic response between visual work and written text constantly propagates new exploration. Regarding the ideas around fake-ness and the hyper normal, the notion of using Photoshop files of bound book and artwork frame mock-up files was intriguing. I loved the idea of immersing the real drawings into fake, digital images. This dichotomous combination of both real and fake also presented interesting possibilities with the design of the book. The page layout was designed around the proportions of the artwork frame in the fake Photoshop images—the geometry of the fake image dictating the overall proportion of the real book—a ridiculous design approach which I am very happy with!

Book page layout determined by the dimensions of the fake Photoshop mock-up images

The drawings, text, and Photoshop mock-up images were eventually designed into production files for a printed book which has been produced for my online portfolio and current body of work.

Printed and bound book cover

Jayson designs, draws, writes, and documents his world at jaysonzaleski.com. He can be reached at [email protected].

References

1. Curtis, Adam. HyperNormalisation, 2:46, March 23 2016, https://thoughtmaybe.com/hypernormalisation/

2. Ibid.

3. Achbar, Mark & Wintonick, Peter. Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media, (Necessary Illusions / The National Film Board of Canada, 1992), DVD.

4. Gonczy, Anne Marie L.. Modern Money Mechanics: A Workbook on Bank Reserves and Deposit Expansion, (Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 1992), p.16.

5. Curtis, Adam. HyperNormalisation, 2:46, March 23 2016, https://thoughtmaybe.com/hypernormalisation/

6. Ibid.

7. Mason, Paul. Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future, (Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2016).

8. Achbar, Mark & Abbott, Jennifer. The Corporation, (Big Picture Media Corporation, 2004), DVD.

9. Russell Brand. Interview with Shoshana Zuboff, Under The Skin with Russell Brand, podcast audio, January 29, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VPVi1K7P9Ck

10. Russell Brand. Interview with Adam Curtis, Under The Skin with Russell Brand, podcast audio, March, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xBy08P7tHPQ

11. Mason, Paul. Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future, (Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2016).

12. Ibid.

13. Tiku, Natasha. The Google engineer who thinks the company’s AI has come to life. The Washington Post, 11 June 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/06/11/google-ai-lamda-blake-lemoine/. Accessed 19 June 2022.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK