The 19th-Century Philosopher Who Predicted Data Overload

source link: https://ericweiner.medium.com/the-19th-century-philosopher-who-predicted-data-overload-67eee2af7497

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

The 19th-Century Philosopher Who Predicted Data Overload

When it comes to information, more is not always better

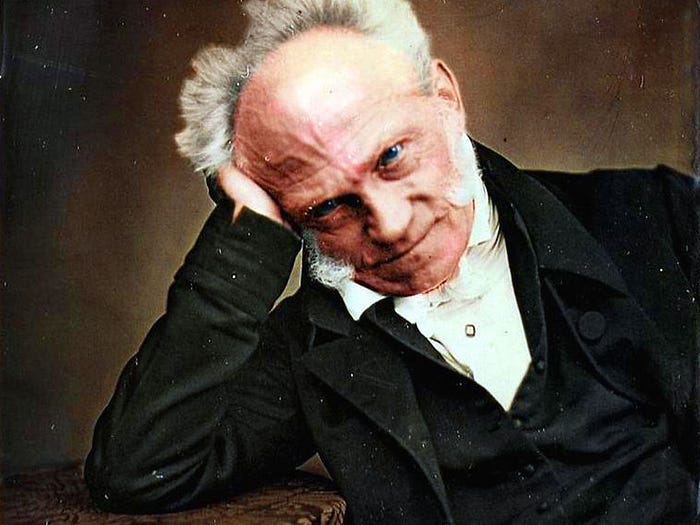

Photo: Pennsylvania State University

Ours is a noisy time, but it is not only acoustic noise that is worrisome. A more treacherous clamor is mental noise: the flood of images and information — some useful, most not — that bombards us incessantly. The decibel levels for mental noise are off the chart.

The magnitude of this problem may be larger than ever, but the problem is not new. Some 150 years ago, a grumpy German philosopher (redundant, I know) named Arthur Schopenhauer worried aloud about the proliferation of information, and with it mental noise.

Mental noise does more than disturb. It masks. In a noisy environment, we lose the signal, and our way. Some two centuries before email, the cluttered inbox worried Schopenhauer.

In his essay “On Authorship,” the philosopher foreshadows the mind-numbing racket that is social media, where the sound of the true is drowned out by the noise of the new. “No greater mistake can be made than to imagine that what has been written latest is always the more correct; that what is written later on is an improvement on what was written previously; and that every change means progress.”

We make this mistake — call it Schopenhauer’s Folly — every time we click mindlessly, like a lab rat pulling a lever, hoping for a reward. What form this reward will take we don’t know but that is beside the point. Like Schopenhauer’s hungry readers, we confuse the new with the good, the novel with the valuable.

We humans are not information-processing machines, any more than we are hunting-and-gathering machines. Just as we need time to digest our prey (or our kale salad), we need time to make sense of the information we’ve consumed.

I am guilty of falling for Schopenhauer’s Folly. I’m constantly checking and rechecking my digital vital signs. While writing this paragraph, I have checked my email (nothing), opened my Facebook page (Pauline’s birthday, must remember to send her a note), placed a bid for a nice waxed canvas backpack on eBay, checked my email again (still nothing), ordered a disturbingly large quantity of coffee, upped my bid for that backpack, and checked my email again (still nothing).

But, you say, you can’t afford to tune out, not now, with the cultural wars heating up and an actual war burning in Europe. I disagree. In fact, you can’t afford not to tune out. As I’ve written, monitoring events is not the same as doing something about them. You are not helping the people of Ukraine or a young woman seeking reproductive care by wringing your hands and drowning in the mental noise.

We humans are not information-processing machines, any more than we are hunting-and-gathering machines. Just as we need time to digest our prey (or our kale salad), we need time to make sense of the information we’ve consumed. Undigested information is worse than no information, and a surplus of data is more dangerous than a lack of it.

The excess data act like a dense fog, clouding our vision — or, to switch metaphors, making sense of excess information is like trying to have a deep conversation in an extremely noisy restaurant. The Internet has laid bare this fundamental problem, but it did not create it. Every age has its own Internet, its own seductive distractions.

In Schopenhauer’s day, it was the encyclopedia. First developed in France during the 18th-century, they were impressive for any age. Why puzzle over a problem when the solution is readily available in a book? Because, answers Schopenhauer, “it’s a hundred times more valuable if you have arrived at it by thinking for yourself.” Too often, he said, people jump to the book rather than stay with their thoughts. “You should read only when your own thoughts dry up.”

Substitute “click” for “read” and you have our predicament. We confuse data with information, information with knowledge, and knowledge with wisdom. This tendency worried Schopenhauer. Everywhere he saw people scrambling for information, mistaking it for insight. “It does not occur to them,” he wrote, “that information is merely a means toward insight and possesses little or no value in itself.”

I’d go a step further. This excess of data — noise, really — has negative value and diminishes the possibility of insight. Inundated with the voices of others, we’re unable to hear our own.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK