A Story of Betrayal: CSIRO’s War On TS | microkerneldude

source link: https://microkerneldude.org/2022/02/17/a-story-of-betrayal-csiros-war-on-ts/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

A Story of Betrayal: CSIRO’s War On TS

It’s now almost 9 months since CSIRO’s Data61 announced it was abandoning the Trustworthy Systems (TS) group. In previous blogs I have fact-checked the CSIRO CEO’s Senate Estimates evidence as well as CSIRO’s public statements about this, and pointed out how these statements omitted important facts or were outright dishonest.

Before I leave this chapter behind for good, I feel a responsibility for shedding a bit more light onto the machinations inside the organisation that is funded by my (and your) tax dollars. I’ll show that the abandoning of TS didn’t come out of the blue, but was the culmination of years of undermining what was arguably the most successful group in Data61. I’ll skip over the outright lies I encountered (of which there were plenty), as I have better things to do than defend a defamation case where I’d have to rely on the memories of other people (even though it would be fun to table all that material in court and watch people being cross-examined). There’s plenty of other appalling stuff to talk about.

Specifically, I’ll demonstrate that the abandonment of TS wasn’t just the result of a change of strategy (which in itself would be highly inconsistent). To the contrary, I’ll show that the dismantling of TS was going on for years.

Everything factual I write below (except where clearly expressed as suspicion or speculation) is witnessed and documented. In fact, I think this information should all be FoI-able (and I herewith explicitly wave my privacy rights in respect to any documents relevant to this blog). Should you succeed in accessing any of them through FoI then feel free to shoot me a copy, I’ll happily put it up here.

Pre-History

How did we end up in CSIRO’s Data61? Not voluntarily.

TS (under the previous names ERTOS and SSRG) came to fame in NICTA, the research organisation set up by the Australian government around 2003. After some false starts it became a great organisation, committed to excellence, and encouraging risk-taking and a long-term view. It was an environment where TS prospered, and achieved things no-one else could (and few thought even possible), becoming famous around the world for our work on creating and verifying the seL4 microkernel, and related activities. Core to that success was our ambition, aiming high and working hard to achieve our goals. This was enabled by a critical mass of excellent people, and the strong integration of complementary skills, especially operating system (OS) design and implementation with formal methods (FM). The team was worldwide unique in this, and made the best of it.

The federal government in its wisdom de-funded NICTA, and it was merged with the ICT parts of CSIRO to form Data61 in July 2016.

Early CSIRO Years

Money was tight after the merger, and there were budget cuts right from the beginning. Despite management assurance that cuts would be vertical, the opposite was true, cuts were horizontal, across the board. Despite our track record, we were probably hit hardest.

Why? Because we were so successful.

We had a large amount of external revenue, resulting in many people hired on fixed-term positions (while the rest of Data61 staff were mostly continuing positions). This made it easiest to cut TS, by not extending positions.

Sounds more than a bit like penalising success, doesn’t it?

The “justification” given by management was the impending “funding cliff” for TS. We had at the time a number of projects nearing the end of their funding period. Among them was the DARPA HACMS program, by any definition a huge success, which demonstrated that “this formal methods stuff” was useful in the real world, leading to a massive re-think in US defence circles. HACMS came to an end in early 2017 (although there were some subsequent transition projects that provided further funding), other projects winding up at a similar time. While we notionally had no follow-up funding lined up, we knew it would come within a year or so (as it did), and had set aside significant reserves to bridge that period. As soon as we became part of CSIRO, management took away all of our reserves.

To add insult to injury, a middle manager told us “you should have planned better” – that manager was well aware of our reserves having been taken! Rarely in my whole life was I as angry as at that moment, and I really had to constrain myself from turning violent. Just mind-boggling.

It should be obvious to everyone that grant money and other external revenue for a research group are inevitably lumpy, and you need to smooth it out, by creating a financial buffer. The highly-qualified people we need for our work in TS don’t grow on trees, you can’t just fire them and then expect to re-hire a year later. Besides, such hire-and-fire attitudes are obviously poison to team culture (and TS always prided itself of a positive, supportive culture). Plus our people have highly sought-after skills, so you hold on to them as long as you can. In contrast, the attitude among CSIRO management seems to be that people are fungible, you can simply shift them from one job to another. (I have seen that attitude at work many times in different contexts, hard as it seems to believe.)

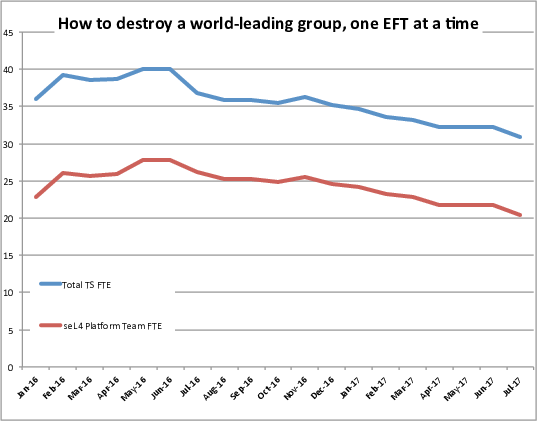

The result is shown in the chart on the right: The core seL4 team lost more than a quarter of its staff in the course of a year – a terminal decline unless reverted. Amazingly, in April’17 the DARPA I2O Director (one step down from DARPA’s boss) wrote a letter to Data61 management pleading not to defund us. Didn’t have much effect.

The consequences were predictable: The TS team, which always prided itself for under-promising and over-delivering, ran massively overtime on a key project – a direct consequence of the management-forced staff attrition, done despite plenty of warning. Did the responsible manager get sacked? Of course not, despite the detrimental effect this had on team morale as well as our reputation.

Working on Plan B

We clearly needed a way out of this situation, and I was working on a Plan B from late 2016. The big challenge was, of course, the lack of a financial buffer, which meant it wasn’t possible to just move the team across to UNSW or a commercial entity. For years I had brought in millions a year of external funding for the group, and brought it all to NICTA (and then Data61), nothing of significance went to UNSW. Consequently I had very limited reserves I could control at UNSW, and they were quickly used up to rescue a small number of most important people Data61 refused to keep on. So, not much could happen until at least one big externally-funded project would come in.

This happened throughout 2017. We knew from Q2’17 that we would be getting several large projects – demonstrating that the “funding cliff” was non-existent.

When, towards the end of the year, I had a big project lined up that I was going to take to UNSW, Data61 management’s attitudes changed dramatically: They now agreed to conditions that allowed us to operate as we needed to.

Right of First Refusal and Staffing Flexibility

In exchange, I had to agree that any external funding I generated that could be taken to CSIRO had to be offered to them (right of first refusal).

This means Plan B was off (for the time being).

But I did at around the same time attract funding that could not be taken to CSIRO, as some funding sources aren’t accessible to them (eg the Australian Research Council, ARC). This means that I had to hire staff at UNSW to work on those projects. Which creates a new challenge: For a tightly integrated group such as TS it doesn’t make sense to have all staff allocated to one particular project (or group of projects) permanently. The needs of many projects change over time, and we had always moved people between projects. In fact, we considered this part of skills development: Giving junior staff exposure to multiple projects and tasks.

To make this work in practice, an agreement was put in place that allowed us to move staff between UNSW and CSIRO projects, and true up salary expenses quarterly. This worked very well while it lasted.

The special agreement with UNSW even helped Data61 get around internal limitations of staffing numbers. We ended up hiring all new TS staff through UNSW, even when they were to work primarily on CSIRO projects – to help Data61 manage their head-count limit, all with the explicit blessing and support of Data61 management.

But Data61 management rewarded our (and UNSW’s) helpfulness by screwing us, details below.

Back to the Bad Old Days

Things worked well as long as we attracted plenty of money. I don’t have the numbers to prove it, but I’m fairly confident that TS was by far Data61’s biggest source of revenue that was not Australian tax dollars.

However, as soon as a bunch of projects neared completion, without a seamless transition to new funding, things changed again. Our agreements were simply abandoned, without even the promised consultation. I had adhered to our agreements to the dot, Data61 management didn’t.

But it got worse.

Things went back to where they were in 2016: TS was being dismantled, by not extending expiring fixed-term positions, and not replacing any voluntary departures. Except that it was actually worse than that.

Outsourcing Redundancies to “Partners”

There were government funding cuts at the time, and CSIRO announced proudly that they would manage them without sacking people. Which is technically correct, because they outsourced the sackings.

In Sep’20, Data61 management told UNSW that they were revoking funding for all the positions we had hired at UNSW for Data61 projects (and on Data61 money), and hat UNSW would have to let go of the staff or find other funding sources for them. Some of them had been hired on multi-year positions, with the explicit approval of Data61 management! There is no other way of putting it: CSIRO outsourced their redundancies to their “partner” UNSW – without any negotiation! UNSW was forced to make people redundant, with the reputational risk resulting from that, so CSIRO could claim that they were weathering the government funding cuts without redundancies. Way to treat your partners, who were doing you a favour!

I’m not a lawyer, but it seems to me that UNSW would have an excellent case of suing CSIRO for the money, given there were written commitments to fund those UNSW positions. UNSW probably decided the amount at stake wasn’t worth an expensive and high-profile court case, and in the end the loyal TS people were thrown under the bus. I can’t blame UNSW too much for that decision, which was really forced by Data61 management’s actions. But I’ve rarely seen the level of unethical behaviour as displayed by Data61 management in this issue, and it’s something for which I will never forgive those individuals.

Cancelling a US Air Force Grant

Our high-profile, multi-award-winning Time Protection project is funded through a grant from the ARC. As CSIRO is not eligible to apply for ARC funding, this had to be a UNSW project (in collaboration with the University of Melbourne), without violating the first-right-of-refusal agreement.

In 2019 the US Air Force’s Asian Office of Aerospace Research and Development (AOARD) also offered funding for the project. AOARD were aware of the ARC funding, the awarded amount of which was about 2/3 of what we had applied for, so it was great that AOARD offered to cover part of the shortfall. AOARD had been funding a number of our projects for many years, going back to the NICTA days, and were generally highly supportive of us.

It would have been easiest to send the AOARD money through UNSW, given that existing project activities were all at UNSW and Melbourne Uni. However, in line with the right-of-first-refusal agreement, we offered the money to CSIRO, which accepted it. This was a one-year grant with two annual extension options (at AOARD’s discretion).

In October 2020, AOARD exercised the first extension option and gave us a second year of funding, which was accepted by Data61 management immediately, was invoiced and the money received by CSIRO soon after.

Then a few weeks later, completely out of the blue, Data61 management decided to return the funding to AOARD. I was livid – I had never seen anything like this happen before! I told them that if they didn’t want the money, they should simply hand it to UNSW and let them be responsible for the project. (There was a precedent for that, where a TS-affiliated colleague from another university got money from Intel, which went to CSIRO under right-of-first-refusal, and CSIRO unceremoniously handed it to the respective university.) CSIRO refused to do this, and just offered to have the CSIRO bizdev person in charge put me in contact with AOARD. (As if I needed the help of some nobody to talk to the organisation that had been funding our work for years, because they knew and trusted us! Of course I had been talking to them immediately, but their hands were tied as long as CSIRO didn’t cooperate, which they did not.)

In the end I was powerless to stop the destructive move, and the money was lost irrecoverably. This could not have happened had I taken it through UNSW in the first place, but I honoured the right-of-first-refusal deal. CSIRO’s way of saying “thanks” was to screw me and the other people on the project.

On 1 December 2020 I made a formal complaint against Data61 management, alleging

- lack of due process

- lack of transparency, in clear violation of CSIRO Values

- lack of honesty in the justification

- discriminatory treatment (given the Intel precedent)

- reckless and unjustified action that undermines my reputation.

Nothing happened, despite multiple reminders. Finally after two months, and another reminder, I got a response within less than a day. The complaint was dismissed on 4 March 2021, without any attempt to address any of the specific issues I had raised, and simply claiming (falsely) that my failure to take up the offer to put me in touch with AOARD had undermined my case. (I replied that I had been talking to them, but got no response.)

Unfortunately, this episode is completely in line with my experience of how CSIRO management operates. No more than lip service is paid to processes, consultation and “CSIRO values”. Of course, after all I’ve seen I expected nothing else, but went through the process to have things documented. I repeat that I explicitly wave my right to privacy in this matter, in case someone wants to FoI the paper trail.

Bad Old Days – in More Ways that One

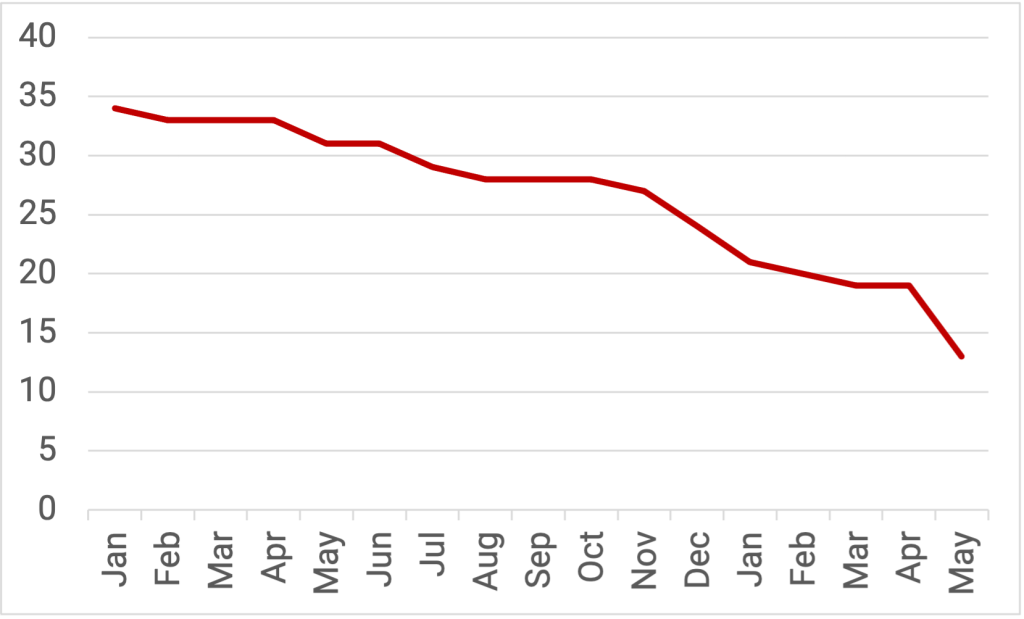

2020–21 really was déja-vue. They ran down our staffing levels, as shown in the chart below. And they didn’t care about consequences, including how critical a particular person was to the externally-funded projects. I kept warning about not being able to deliver; management didn’t care. The result was that, for the second time, and again squarely due to the actions of Data61 management, we were horribly late on an externally-funded project. In fact, the late project was part of the very contract I wanted to take to UNSW in 2017–18 but Data61 was keen to get. The project was abandoned by the funders when Data61 kicked TS out.

The chart on the right shows our declining staffing levels during the period. The big dip from Nov’20 to Jan’21 were the outsourced redundancies; the dip in April’21 is when our verification stars left to set up Proofcraft, and my long-standing brother-in-arms Peter Chubb left in disgust. (Fortunately I had enough money left to hire Peter at UNSW, where he continues to be the backbone of systems work in TS.) But it’s also clear that the assault on TS started well before that, and continued to the May’21 announcement of shutting the group down completely. By that time, we had already lost half of our staff.

The End

This was the situation when in May’21, Data61 management announced that the TS group would be wound up. While it came as a shock to most staff, the above shows that the writing was on the wall, and I fully expected it. Needless to say, morale had been low for a while. Nevertheless, the awesome TS team kept delivering, albeit at (temporarily) reduced efficiency.

TS survived the betrayal, as you all know. How this happened, and how it got us into a much stronger position than we had been in a long time, will be the subject of the final blog in this series. I want to keep the way forward well separated from the depressing past, and simply stop thinking about CSIRO and the dishonesties and betrayals that are associated with it.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK