The Media Is Biased, But Not in the Way You Think

source link: https://gen.medium.com/the-real-media-bias-7a91d35e70fa

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

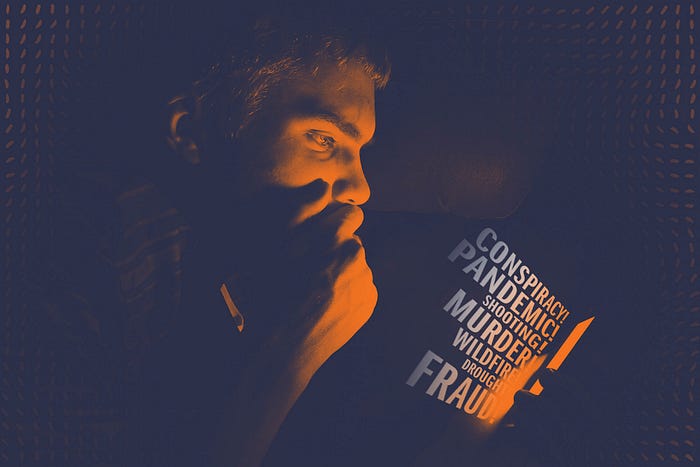

The Media Is Biased, But Not in the Way You Think

News outlets fixate on the negative

The critics are right. The mainstream media is biased. It is not a political bias, though, no liberal or conservative slant, but something even more insidious: a bad-news bias.

During my decades as a daily journalist, at The New York Times and NPR, I knew that reporting on happy people and places wasn’t going to advance my career. No one told me this. They didn’t need to. The bad-news bias is simply understood.

“If it bleeds, it leads,” goes the cynical newsroom slogan. A quick scan of media sites bears this out. A ceaseless parade of disasters, human and natural, current and forecast, and all framed in the most negative light.

A case in point is a recent article that ran in Axios. (I don’t mean to pick on Axios; this happened to catch my eye.) The headline read: “Rapid nasal COVID tests feared to be returning false negatives.” That sounds bad, alarming even. But read on and you discover the basis for the story is a “small preprint study” of thirty people, four of whom received a false negative. It suddenly doesn’t sound so catastrophic. Then we learn that there is emerging evidence that “saliva swabs may be better for detecting Omicron than nasal swabs.” That sounds like, well, good news, or at least not as bad as the headline suggests.

The story isn’t factually inaccurate, but it is framed in an unnecessarily negative way. A news story can be 100 percent factually accurate yet not fully truthful. The truth is more than a collection of facts, and journalists are more than underpaid, underappreciated conveyors of facts. They are underpaid, underappreciated conveyors of truth, or at least small truths which, together, make up the larger whole that drives public policy and shapes our lives.

The bad-news bias is a global phenomenon but it is most pronounced in the U.S. One study found that in their pandemic coverage, media outlets in the U.S. struck a far more negative tone than their counterparts abroad: 91 percent of the U.S. stories were negative versus 54 percent overseas. The mainstream US media is even more negative in their coverage of COVID-19 than scientific journals, the study found.

By focusing relentlessly and almost exclusively on bad news, media outlets are endorsing a worldview that doesn’t jibe with what legendary reporter Carl Bernstein considers journalism’s prime objective: relaying “the best obtainable version of the truth.”

There is a psychological basis for the emphasis on bad news. It’s called the “negativity bias,” and it is deeply rooted in our psyches. Negative events make deeper impressions than positive ones as several studies have found. From an evolutionary perspective, this propensity makes sense. In order to survive, it was more important that early humans recalled the location of the lion den, rather than that beautiful rock formation. One might inspire, but the other might kill you. The problem: we have moved past the days when lions threatened us yet we’re still saddled with brains that light up when confronted with perceived threats.

The constant drumbeat of negative news has real-world consequences. Exposure to coverage of mass violence events, such a terrorist attacks, “may render some individuals more vulnerable to mental health consequences” such as flashbacks and intrusive memories, one study found. Another study tracked more than 4,000 adults nationwide in the weeks following the 2013 Boston marathon bombings and found that many suffered from “high acute stress.” Those who consumed a lot of new coverage — six or more hours daily — were nine times more likely to report high acute stress than those who consumed less news. If news organizations are concerned about “audience impact,” as they should be, then what is more impactful than the audience’s collective mental health?

I know, journalists aren’t in the mental health business, or the sugar-coating business. And, yes, if you want to live in a place where the newspapers are filled with nothing but good news, move to North Korea. I’ve heard all the excuses for maintaining the bad-news bias. They don’t wash. The fact is: reflexively negative journalism is just as lazy and unsatisfying as reflexively positive journalism.

Much of journalism these days falls into the category of informed speculation, which is fine, but more often than not those speculations latch onto worst-case scenarios. That’s because such grim predictions are cost-free, for the journalist at least. The reporter who predicts the sky is falling is deemed a clear-eyed realist while the one who suggests the sky may not, in fact, be falling is dismissed as naive, the profession’s harshest smack-down.

A friend, a senior editor at a major newspaper, balked when I suggested his organization infuse its coverage with solutions as well as problems. “We can’t be seen as endorsing any particular solution,” he said. Fair enough, but news organizations are already in the endorsement business. By focusing relentlessly and almost exclusively on bad news, they are de facto endorsing a worldview that doesn’t jibe with what legendary reporter Carl Bernstein considers journalism’s prime objective: relaying “the best obtainable version of the truth.” I like that. Not “the best available version of the truth that paints the bleakest possible picture,” but the best available version of the truth in its entirety — the bad, yes, but also the good.

To be clear: I’m not suggesting journalists ignore bad news or in any way whitewash it. What I am suggesting is that journalists place bad news in perspective and give credible solutions the coverage they deserve. What I am suggesting is a regular dose, not the occasional booster, of intelligent optimism, a worldview grounded in facts and subjected to the same rigors as any other work of journalism, but without the reflexive negativity.

I’m not talking about “feel-good” stories but, rather, something more substantive: rigorous solutions journalism. The difference between a feel-good story and a serious work of solutions journalism is that the former shines a fleeting beam of light on the exception to the rule while the latter shines a bright and steady spotlight on an emerging new rule.

There are glimmers of hope. The Washington Post publishes“The Optimist,” a weeklynewsletter that highlights what went right in the past seven days. At The New York Times, David Leonhardt regularly calls out the media’s bad-news bias in its pandemic coverage.

It’s a start but it is not enough. For now, these efforts are a sideshow, an afterthought that, like a chocolate mint after an atrocious dinner, is supposed to remind us that it’s not all bad. Too often, positive(or at least less negative) coverage is dismissed as “feel-good stories.” The moniker is slung as an insult, synonymous with lazy journalism. But why? What is wrong with a story that makes you feel good? Why is it okay for a news report to send you spiraling into a dark place of despair but not okay for it to make your heart sing? Not necessarily an entire song, but a refrain or two.

Besides, if news is defined as events out of the ordinary — man bites dog — then in a world of suffering and despair, surely the hopeful story qualifies as news.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK