A Decision Tree for Picking the Right Type of Survey Question

source link: https://measuringu.com/survey-question-decision-tree/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

A Decision Tree for Picking the Right Type of Survey Question

Crafting survey questions involves thinking first about the content and then about the format (form follows function). Earlier, we categorized survey questions into four content types (attribute, behavior, ability, or sentiment) and four format classes (open-ended, closed-ended static, closed-ended dynamic, or task-based).

As with any taxonomy, there are several ways to categorize response options (e.g., open- vs. closed-ended). We prefer and recommend starting with the goal of the question and then picking the response option that best achieves that goal while minimizing the burden on the respondent.

Often more than one response option will meet a goal, but we’ve put together a decision tree that should help narrow your choices.

As shown in Figure 1, the tree shows the flow from Goal to the recommended type of question. The rest of this article describes the decision points in the tree and provides guidance for each decision.

Figure 1: Decision tree for picking the right type of survey question.

Discovery or Measurement?

The first decision you need to make is whether the goal of the question is to discover something or to measure something.

Discovery

Discovery is a key aspect of qualitative inquiry. Open-ended questions are well suited for discovering things with minimal response bias. For example, Figure 2 shows an open-ended question designed to discover the kinds of problems respondents experienced on their last visit to a website. The resulting data require significant effort to categorize and count, but they aren’t constrained by a specific set of options.

Figure 2: Open-ended questions to explore self-reported tasks and associated usability problems (created with MUIQ).

Measurement

In contrast, Figure 3 shows a closed-ended question that lists problems that have been hypothesized to happen, either through team discussion or previous research. Presenting options with this format makes them easier to count reliably.

Figure 3: Sample problem list (created with MUIQ).

Measurement makes up the bulk of the decision tree and accounts for most of the question types in UX/CX surveys.

As a practical note, when designing questions whose primary purpose is measurement, you can design hybrids that allow for some discovery by making one of the responses an open-ended “Other” option (see Figure 4). Also, any primarily measurement-focused question can be dynamically followed by an open-ended question designed to get at the why behind the measurement. Take care not to do this too much because it can fatigue respondents. A key driver of survey dropout is excessive survey length.

Figure 4: Sample problem list with open-ended “Other” option (created with MUIQ).

Categorical or Not?

When focusing on measurement, the next question to consider is whether the closed-ended responses contain categories. For example, many attribute questions tend to be categorical (gender, education, age, location). Some categorical questions have a natural order (e.g., age, income), while others do not (e.g., gender, problem lists).

With categorical data identified, your next decision is whether participants can select only one response (mutually exclusive) or multiple responses (not mutually exclusive).

Not mutually exclusive

When the categorical question doesn’t have a natural order and respondents could reasonably select more than one response option, the appropriate question type is Multiple Choice with Multiple Selection, also known as “Select all that apply” questions. Examples of categories that aren’t mutually exclusive include

- Universities attended

- Places lived

- Food delivery services used in the last six months

- Activities performed in a job

- List of problems encountered (e.g., Figure 3)

Mutually exclusive

When a set of categories has a natural order and the options are mutually exclusive, it isn’t reasonable to select more than one. (Some unordered options, such as choosing a preferred design from a set of designs, may also be mutually exclusive.) For example, mutually exclusive categorical options would be appropriate for

- Highest degree obtained

- Current geographic location

- Income

- Number of children

- Frequency of use

One of the most common mistakes we see in surveys is response options presented as mutually exclusive when they really aren’t—a mistake that prevents respondents from giving accurate answers. Other common mistakes that happen with ordered categories are incomplete lists of options and overlapping ranges (e.g., Age: 10–20; 20–30; 30–40; 40–50; 60+. Which option would you select if you were 20? Which would you select if you were 55?).

Frequency

Frequency items are special types of mutually exclusive questions. Figure 5 shows two examples. We generally recommend using specific response options (e.g., more than once a day) rather than nonspecific (vague) options (e.g., rarely).

Figure 5: Two examples of frequency questions (created with MUIQ).

Not Categorical: Ranking, Allocation, or Rating?

The remaining (and the majority of) question types in the decision tree are not primarily categorical. One consequence of collecting categorical data is that the appropriate descriptive and inferential statistical analyses are limited to counts and proportions. It’s possible (and sometimes advisable) to analyze noncategorical data with counts and proportions, but these data aren’t limited to those methods. By assigning numbers to response options, either explicitly or after data collection, you can use sophisticated univariate and multivariate methods to analyze data collected with ranking, allocation, and rating questions.

Ranking

It’s common to ask participants to rank features or content that may appear in a product or website. The primary benefit of ranking is that it forces participants to make tradeoffs and identify what’s important. This helps prevent the “everything is important” problem when having participants rate features (see below on rating).

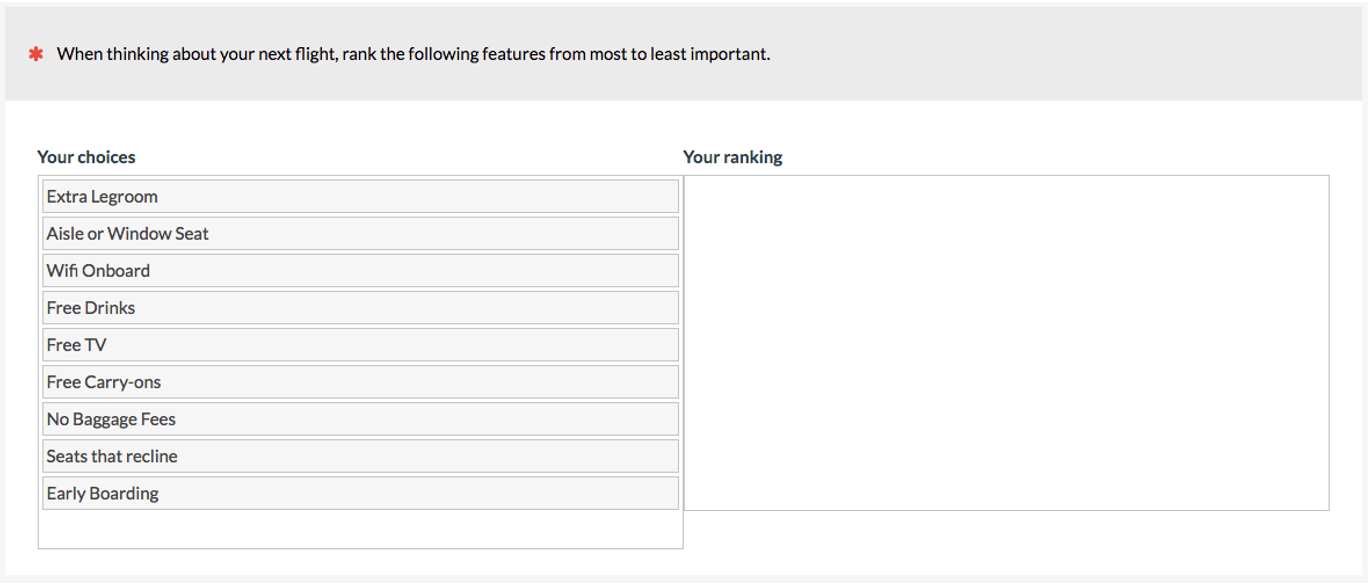

Forced ranking. If you have only a few items for participants to rank (fewer than ten or so), then requiring participants to rank each item is probably not too much of a burden (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Example of forced ranking question (created with MUIQ).

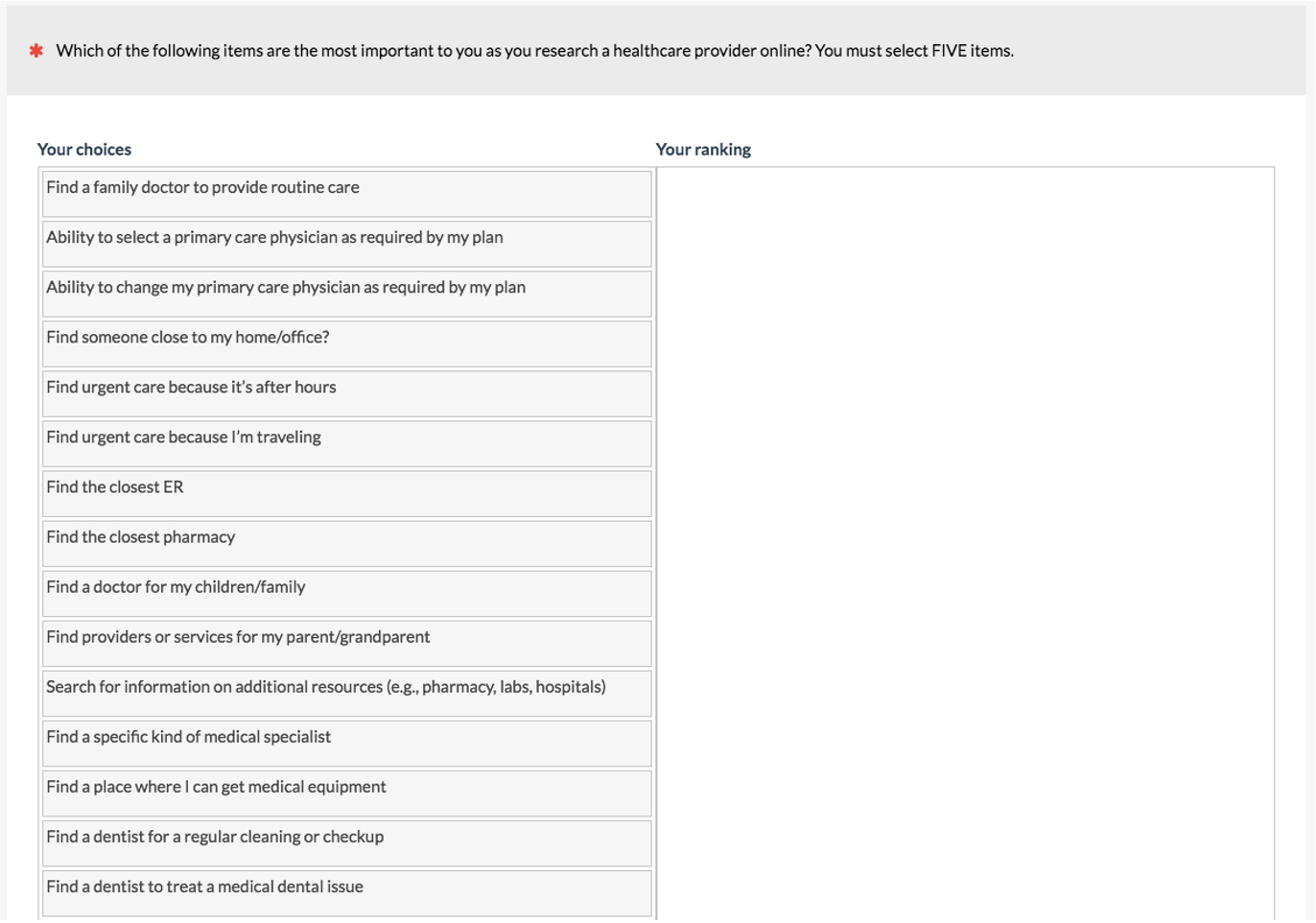

Pick some. If you have a lot of items (more than twenty or so), you’ll want to minimize the burden on the participants by using a pick-some option. We use this option in top-task studies where we often present 50–100 pieces of content or features and ask participants to select their top five (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Example of pick-some ranking question (created with MUIQ).

MaxDiff. When you have many features, an alternative to pick-some is a MaxDiff question type that iteratively presents a subset of the features. This presentation allows participants to select the options that are most and least important. MaxDiff requires specialized software such as our MUIQ platform to present the combinations and calculate ranks and scores (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Example of MaxDiff question (created with MUIQ).

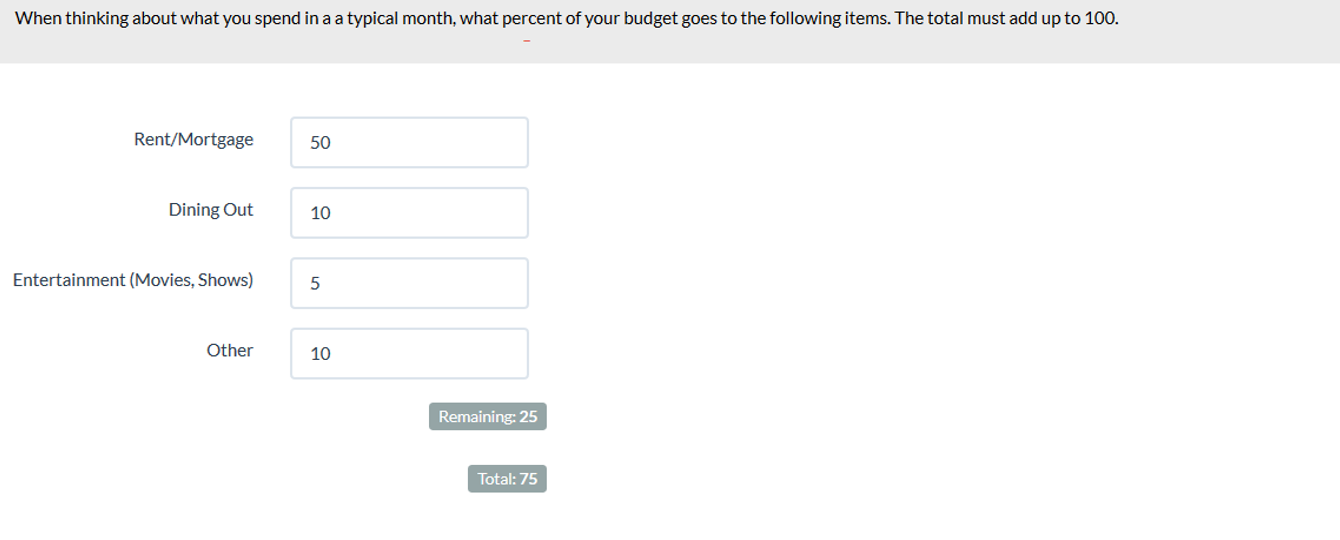

Allocation

A specialized type of forced-choice method has participants allocate points, dollars, percentages, or other amounts to indicate relative importance. Ideally, the software will sum the number to minimize mental math for participants! Figure 9 shows an example.

Figure 9: Example of a fixed-sum question for allocation of a budget (created with MUIQ).

Rating

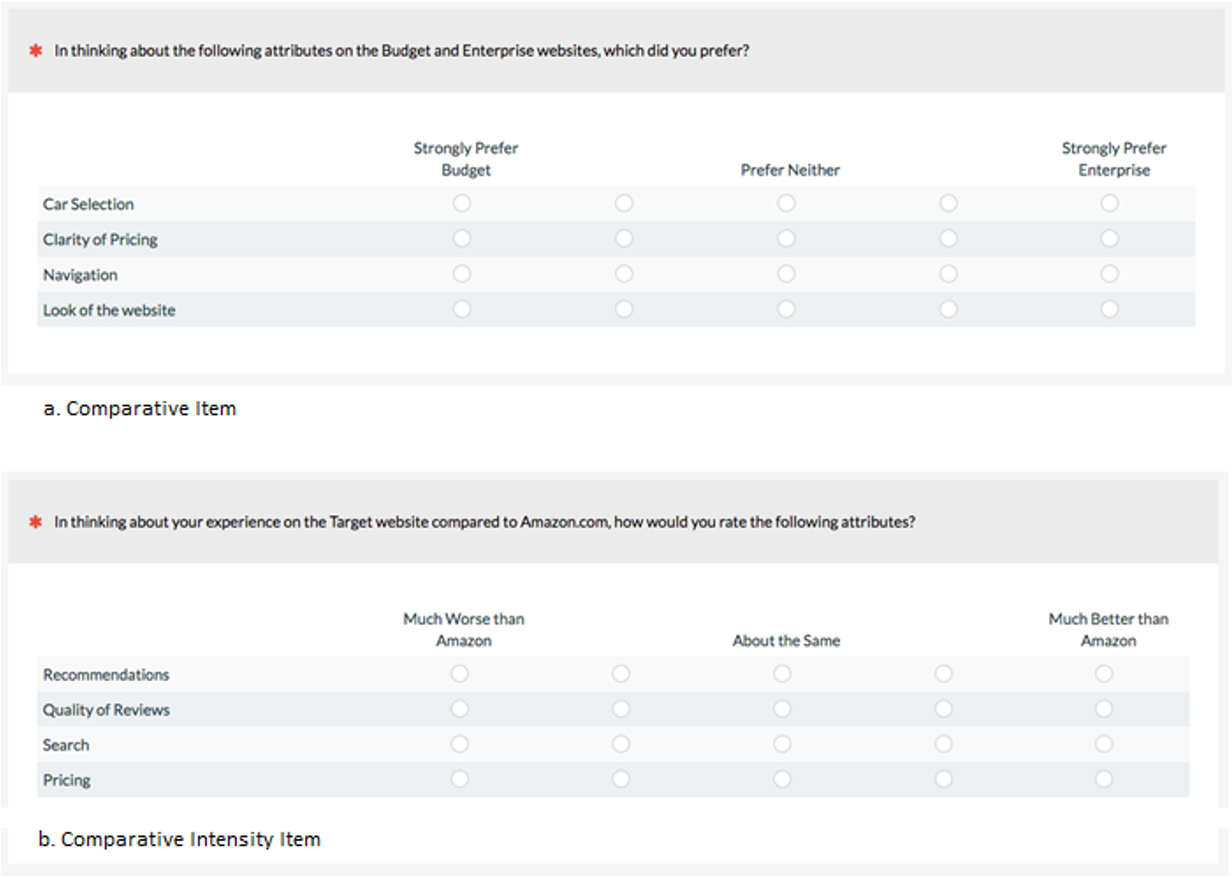

This category encompasses the remainder and bulk of question types. We have divided rating scales into three categories: Comparative, Semantic, and Other General Rating scales.

Comparative questions. Rating scales that ask participants to compare items or compare to a benchmark have a distinct format. Figure 10 shows examples of comparative and comparative intensity questions.

Figure 10: Examples of comparative questions (created with MUIQ).

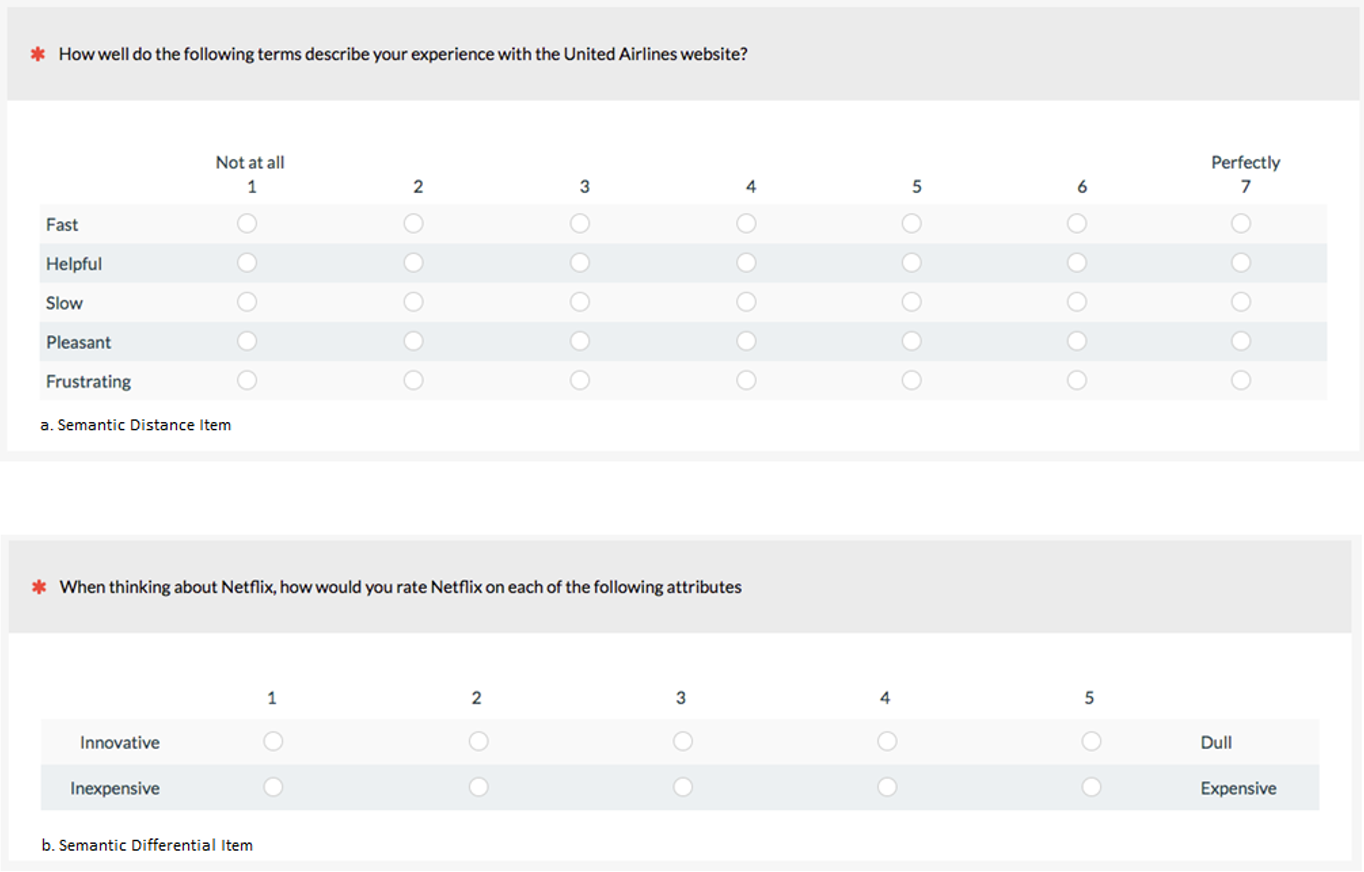

Semantic adjective scales. Semantic adjective scales have participants rate either one (unipolar semantic distance) or two putatively opposite (bipolar semantic differential) adjectives such as “easy” and “difficult.” See Figure 11 for examples.

Figure 11: Examples of semantic scales (created with MUIQ).

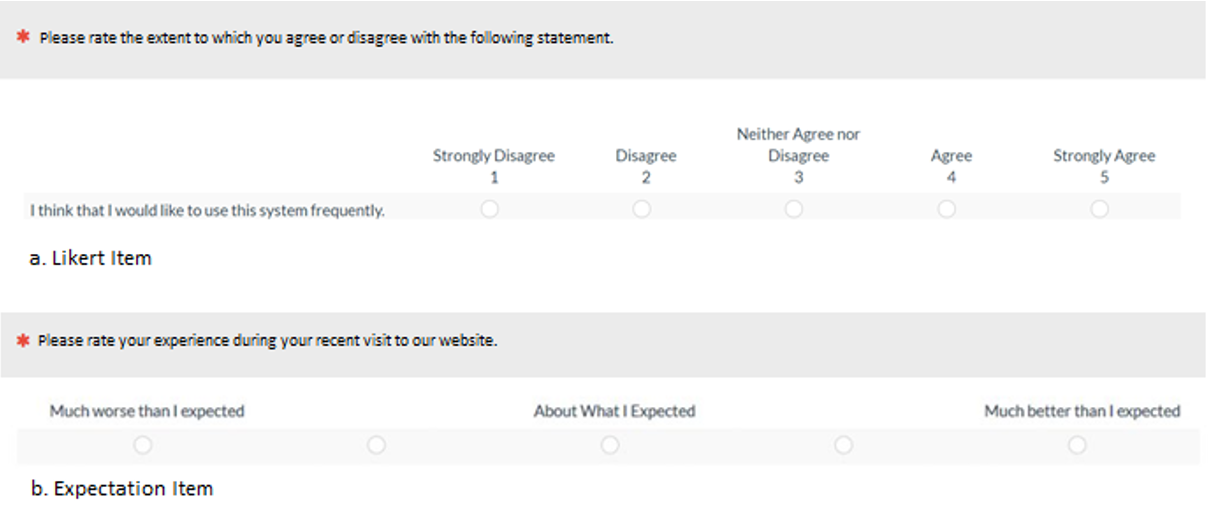

Other rating scales. Other rating scales are those most commonly used in UX and CX research, especially agreement (Likert-type) and expectation (disconfirmation) scales. For examples, see Figure 12.

Figure 12: Examples of Likert and expectation (disconfirmation) rating scales (created with MUIQ).

Using the Decision Tree

Table 1 shows some example goals, which question types achieve the goal, and the path through the decision tree (Figure 1).

GoalQuestion TypePath Through Decision Tree Discover potential uses of a new featureOpen-Ended ItemDiscovery Assess the extent to which the experience of attempting a task matched participants' expectationsDisconfirmation ItemMeasurement > Not Categorical > Rating > Meeting Expectation Determine the relative importance of five product featuresForced Rank ItemMeasurement > Not Categorical > Ranking Assess the extent to which respondents agree or disagree that they are confident in having completed a task successfullyLikert ItemMeasurement > Not Categorical > Agreement Find out which of five video content streaming services respondents have used in the past yearMultiple Choice Item (Multiple Selection)Measurement > Categorical > Unordered > Not Mutually Exclusive

Table 1: Examples of using the decision tree to match goals with question types.

Summary

The number of question types that are available for use in surveys can seem overwhelming. Having a decision tree as a guide to the decisions you need to make can simplify selecting appropriate question types.

These decisions include

- Discovery: When discovery is the primary goal, use open-ended items.

- Measurement: The key decision when collecting measurements is to determine whether the required data is or isn’t categorical.

- Categorical: Categorical data can be ordered or unordered and can be collected with multiple-choice items. You can allow participants to select multiple items when choices are not mutually exclusive, or you can restrict selection to one item when choices are mutually exclusive.

- Not categorical: Noncategorical question types can be classified as ranking, allocation, or rating. Of these types, rating scales are the ones most commonly used in UX and CX research.

UX and CX researchers can use this decision tree when planning surveys to help connect research goals to appropriate types of survey questions.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK