To the moon: defining and detecting cryptocurrency pump-and-dumps

source link: https://crimesciencejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40163-018-0093-5

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Introduction

Cryptocurrencies have been increasingly gaining the attention of the public, and their use as an investment platform has been on the rise. These digital currencies facilitate payments in the online sector without the need for a central authority (e.g., a bank). The market for cryptocurrencies is rapidly expanding, and at the time of writing currently had a market capitalisation of around 300 billion US dollars (CoinMarketCap 2018) making it comparable to the GDP of Denmark (Cryptocurrency Prices 2018). Despite the vast amounts of money being invested and traded into cryptocurrencies, they are uncharted territory and are for a large part unregulated. The lack of regulation, combined with their technical complexity, makes them an attractive target for scammers who would seek to prey on the misinformed. One such scam is known as a pump-and-dump (P&D), where bad actors attempt to make a profit by spreading misinformation about a commodity (i.e., a specific cryptocurrency coin) to artificially raise the price (Kramer 2004). This scam has a long history in traditional economic settings, going as far back as London’s South Sea Company in the 1700s (Brooker 1998), then found a natural home in penny stocks and on the Internet (Kramer 2004; Temple 2000), and has now recently appeared in cryptocurrency markets (Khan 2018; Mac and Lytvynenko 2018; Martineau 2018).

The academic literature on cryptocurrency (crypto) P&D schemes is scarce (for an exception, see the recent working paper of Li, Shin, & Wang, 2018). Thus, this paper will give an overview of what is currently known about the topic from blogs and news sites. To provide a theoretical angle, economic literature related to the topic is examined, and this information synthesised with cryptocurrencies by highlighting the similarities and potential differences. As these patterns are a type of anomaly, literature on anomaly detection algorithms is also discussed. The goal is to propose some defining criteria for what a crypto P&D is and to subsequently use this information to detect points in exchange data that match these criteria, forming a foundation for further research.

What is a pump-and-dump scheme?

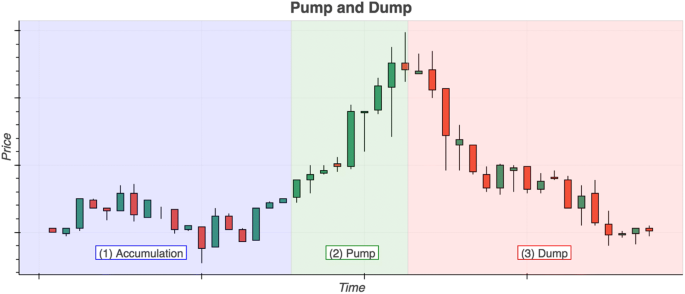

A pump-and-dump scheme is a type of fraud in which the offenders accumulate a commodity over a period, then artificially inflate the price through means of spreading misinformation (pumping), before selling off what they bought to unsuspecting buyers at the higher price (dumping). Since the price was inflated artificially, the price usually drops, leaving buyers who bought on the strength of the false information at a loss. While we do not provide a rigorous crime script analysis (see Borrion 2013; Keatley 2018; Warren et al. 2017) here, Fig. 1 can be viewed as a script abstraction of three main stages—accumulation, pump, and dump. The accumulation phase usually occurs incrementally over a more extended period of time, in order to avoid raising the price before the pump.

What are cryptocurrencies?

Cryptocurrencies are a digital medium of exchange, and they usually rely on cryptography instead of a central institution to prevent problems like counterfeiting. For example, the most popular cryptocurrency is Bitcoin (BTC), and some of its benefits are that it allows for trustless and de-centralised transactions since it is impossible to reverse a payment, and there are no third parties (e.g., banks) involved (Nakamoto 2008). In traditional financial systems, a customer trusts the third-party (e.g., a bank) to update their ledger to reflect the customer’s accounts balance. To the contrary, with Bitcoin, this ledger is distributed across a network, and everyone on the network possesses a copy and can—in principle—verify its contents. That public ledger is known as the blockchain and is the core technology upon which Bitcoin and many other cryptocurrencies rest. There are now many different types of cryptocurrencies, with less widely known ones referred to as ‘altcoins’, and they all run on slightly different technical principles, with different utilities and benefits (Bitcoin Magazine 2017). Besides Bitcoin, some of the other currently more popular cryptocurrencies include Ethereum (https://ethereum.org/), Ripple (https://litecoin.org/), and Litecoin (https://litecoin.org/).

Aims of this paper

In this paper, we set out to achieve three primary goals. First, absent a body of academic research on cryptocurrency pump-and-dump schemes, we provided an initial working formalisation of crypto P&Ds identifying criteria that might help in locating and ideally preventing this emerging fraud problem. Second, we utilise these indicators and propose an automated anomaly detection approach for locating suspicious transactions patterns. Third, to better understand the crypto P&D phenomenon, we zoom in on the exchange level and on the cryptocurrency pairings level. The overarching aim of this paper is to spark academic interest in the topic and to introduce P&Ds as an emerging problem.

Pump-and-dump schemes in the traditional economic context

In the early eighteenth century, con artists who owned stock in the South Sea Company began to make false claims about the company and its profits. The goal was to artificially raise the price of the stock, and then sell it off to misinformed buyers who were led to believe that they were buying a promising commodity. This was referred to as the South Sea Bubble and serves as an early documented example of a P&D scheme (Bartels 2000; Brooker 1998).

In modern times, P&D schemes have predominantly been Internet-based focusing on so-called “penny” or “microcap” stocks, which are smaller companies that do not meet the requirements to be listed on the larger exchanges such as the NASDAQ (Dugan 2002; Temple 2000). Microcap stock exchanges are not held to the same standard of regulation, which implies that there is usually not as much information about the companies that are listed making them easier to manipulate. For example, in the US, large public companies file publicly available reports with the Security Exchange Commission (SEC) which are often analysed by professionals (US Securities and Exchange Commission 2017). Access to and the verification of information is typically more difficult with microcap companies. Misinformation about the stocks is often spread through email spam which has been found to have a net positive effect on the stock price (i.e., the spam is effective in increasing the price, see Bouraoui 2009). In the United States, it is illegal to run a P&D operation on penny stocks, and there are multiple cases of people having charges pressed against them for their participation in a P&D scam (“Developments in Banking and Financial Law: 2013,” 2014; Yang and Worden 2015).

Pump-and-dump schemes in the cryptocurrency context

There is currently a lack of academic literature on cryptocurrency pump-and-dump schemes, so this section seeks to give an overview of the current landscape of cryptocurrency P&D schemes as they have been realised in various blog posts and news articles. In the cryptocurrency context there is an overall slightly different modus operandi than in the traditional context of penny stocks; specifically, this has been seen in the rise of dedicated public P&D groups. These groups have emerged in online chat rooms such as Discord (https://discordapp.com) and Telegram (https://telegram.org) with the sole purpose of organising pump-and-dump scams on select cryptocurrencies (Fig. 2). The number of members in some of these groups is reported to have been as high as 200,000, with smaller groups still running about 2000 (Martineau 2018). Price increases of up to 950% have been witnessed, demonstrating the extent of manipulation these groups are capable of (Thompson 2018). For these P&D groups to achieve the best results, several reports of activity show that they almost exclusively target less popular coins, specifically those with a low market cap and low circulation, since they are deemed easier to manipulate (Khan 2018; Mac and Lytvynenko 2018; Town 2018). Estimating the full scope of the damages caused by cryptocurrency pump-and-dumps is difficult; yet there is some evidence to show that such schemes are generating millions of dollars of trading activity. The Wall Street Journal published an investigative article that looked at public pump-and-dump groups and 6 months of trading activity. They found $825 million linked to pump-and-dump schemes, with one group alone accounting for $222 million in trades (Shifflett 2018). This gives a glimpse of how much monetary activity is generated by these groups, the impact of which could be even greater as many groups presumably operate in private or invite-only groups.

Example of a pump-and-dump chat group with over 40,000 members. Left: Telegram group ‘Rocket dump’. Right: Corresponding exchange data (Binance) of the targeted coin (Yoyo) showing the effect of the pump. The yellow, purple, and maroon lines represent the moving average for the last 7, 25, and 99 days respectively

The pump-and-dump procedure usually consists of the group leaders declaring that a pump will take place at a particular time on a particular exchange, and only after the specified time will the coin be announced (see Fig. 2). After the coin is announced members of the group chat try to be amongst the first to buy the coin, in order to secure more profits. Indeed, if they are too slow, they may end up buying at the peak and be unable to sell for a profit. The ‘hype’ around buying the coin once the pump is announced is due to the short timescale of these schemes: Martineau (2018) reported on two pumps that reached their peaks within 5–10 min. During the pumping phase, users are often encouraged to spread misinformation about the coin, in an attempt to trick others into buying it, allowing them to sell easier. The misinformation varies, but some common tactics include false news stories, non-existent projects, fake partnerships, or fake celebrity endorsements (Martineau 2018; Town 2018). Consider the example where a group of offenders impersonated Internet entrepreneur John Mcafee’s twitter account @OfficialMcafee by including an extra ‘ l ’ in the username (Mac and Lytvynenko 2018). The fake account sent a positive tweet about a particular altcoin and all the users in the P&D group were told to retweet it. Within 5 min. The price of the coin had gone from $30,- to $45,-, collapsing back down to $30,- after about 20 min. Anything which creates a general air of positivity is fair game because the goal is to dump their coins on unwitting investors who have not done their due diligence, by preying on their fear of missing out on the next big crypto investment.

In a move to secure profit for themselves, many pump-and-dump group leaders will often use their insider information to their advantage: because they know which coin will be pumped, they can pre-purchase the coin for a lower price before they announce it. This guarantees them profit while leaving other users to essentially gamble on whether or not they can predict the peak. The fear of missing out and the potential to beat the odds might drive prospective cryptocurrency investors into joining a pump. Group leaders can also guarantee profits by offering access to the pump notification at an earlier stage prior to the group-wide announcement, in exchange for payment. Even a few seconds of temporal advantage are sufficient to potentially place buy orders before others, and thereby obtain cheaper coins, hence increasing the buyer’s benefit from the of the pump-and-dump operation (Martineau 2018).

Due to the fact that the technology behind cryptocurrencies is relatively new, and that most exchanges are unregulated, pump-and-dump manipulation is currently not always illegal; and even where it is, it cannot always be easily enforced. However, governing bodies are beginning to realise the problem, and in the United States the Commodity Futures Trading Commission has issued guidelines on how to avoid P&D scams, as well as offering a whistle blower program (U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission 2018).

Defining a cryptocurrency pump-and-dump

Mitigating and preventing pump-and-dump schemes will require knowledge about their operation, and thus the detection of these pump-and-dump schemes is a step towards the goal of mitigation. To begin searching for and identifying potential P&D type patterns in exchange data, a working definition for what constitutes a P&D is needed. A proposal for defining criteria will be given in this section by summarising the insights regarding traditional and crypto P&D schemes that have been outlined in the previous section. Table 1 summarises some of the key similarities and differences with the respect to the target, tactic, and timescale of traditional penny stock and crypto pump-and-dump schemes.

Table 1 indicates that a crypto P&D seems similar to a penny stock P&D in that assets that share the same properties are targeted. However, in general, it appears that as a result of different tactics the time scale has been narrowed and moved towards near real-time. Just as the digitisation of information via the Internet increased the rate of P&D scams on penny stocks, so too it seems the digitisation of currency itself has increased the rate and speed at which a P&D can take place.

Using the identified characteristics of crypto P&Ds allows us to formulate criteria that could be helpful in detecting P&D patterns in exchange data (Table 2). Specifically, we argue that indicators of P&Ds can be subdivided into breakout indicators which refer to the signals that will always be present during a pump-and-dump, and reinforcers which refer to indicators which may help increase the confidence that the observed data point is the result of manipulation. The volume and price are discussed with an estimation window, referring to a collection of previous data points, of some user-specified length. For example, a moving average over a previously defined time period could be used, which would allow for discussing spikes with regards to some local history. This is not to say that the proposed criteria are sufficient to encompass all crypto P&Ds. Instead, we chose to resort to conservative criteria that are necessary for a P&D and that appear to have emerged based on the information in the previous section.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK