China uses foreign firms to turbocharge its industry

source link: https://www.high-capacity.com/p/how-china-uses-foreign-firms-to-turbocharge

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

(This piece builds on part of another piece I wrote on India’s EV strategy.)

China uses foreign firms selectively to bring in technology and know-how, to build up its domestic suppliers, and to ultimately sow the seeds for homegrown Chinese companies to compete on the world stage.

There are two broad principles at work here. Let’s learn some Chinese.

1. “Market access in exchange for technology” (市场换技术)

China has long been very deliberate in using the allure of the lucrative “China market” to entice foreign firms to set up shop there.

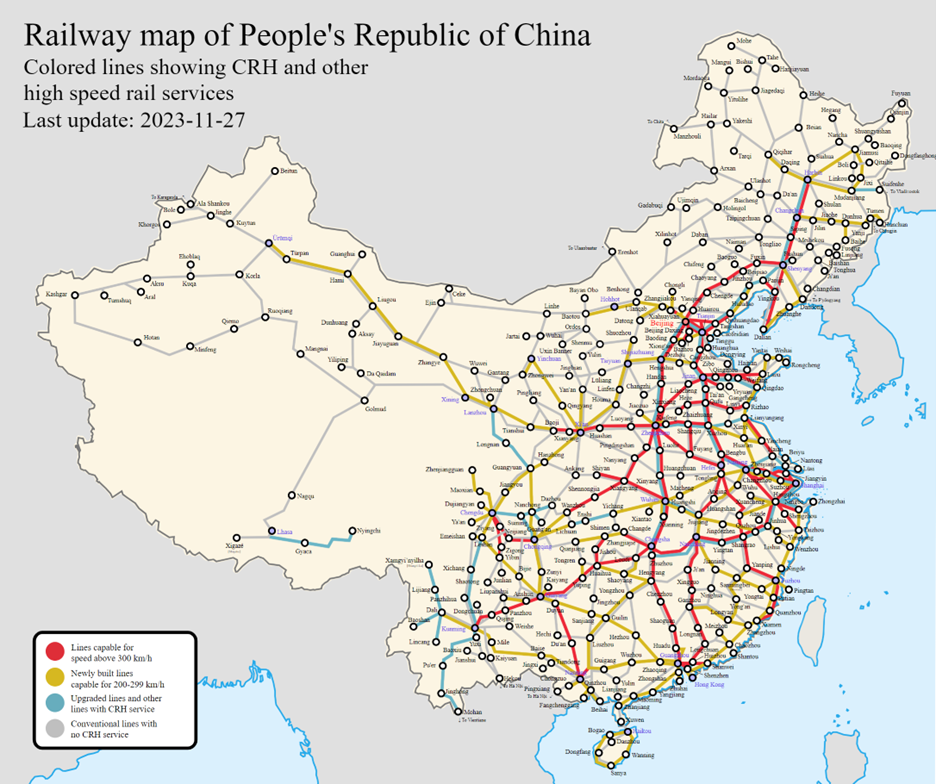

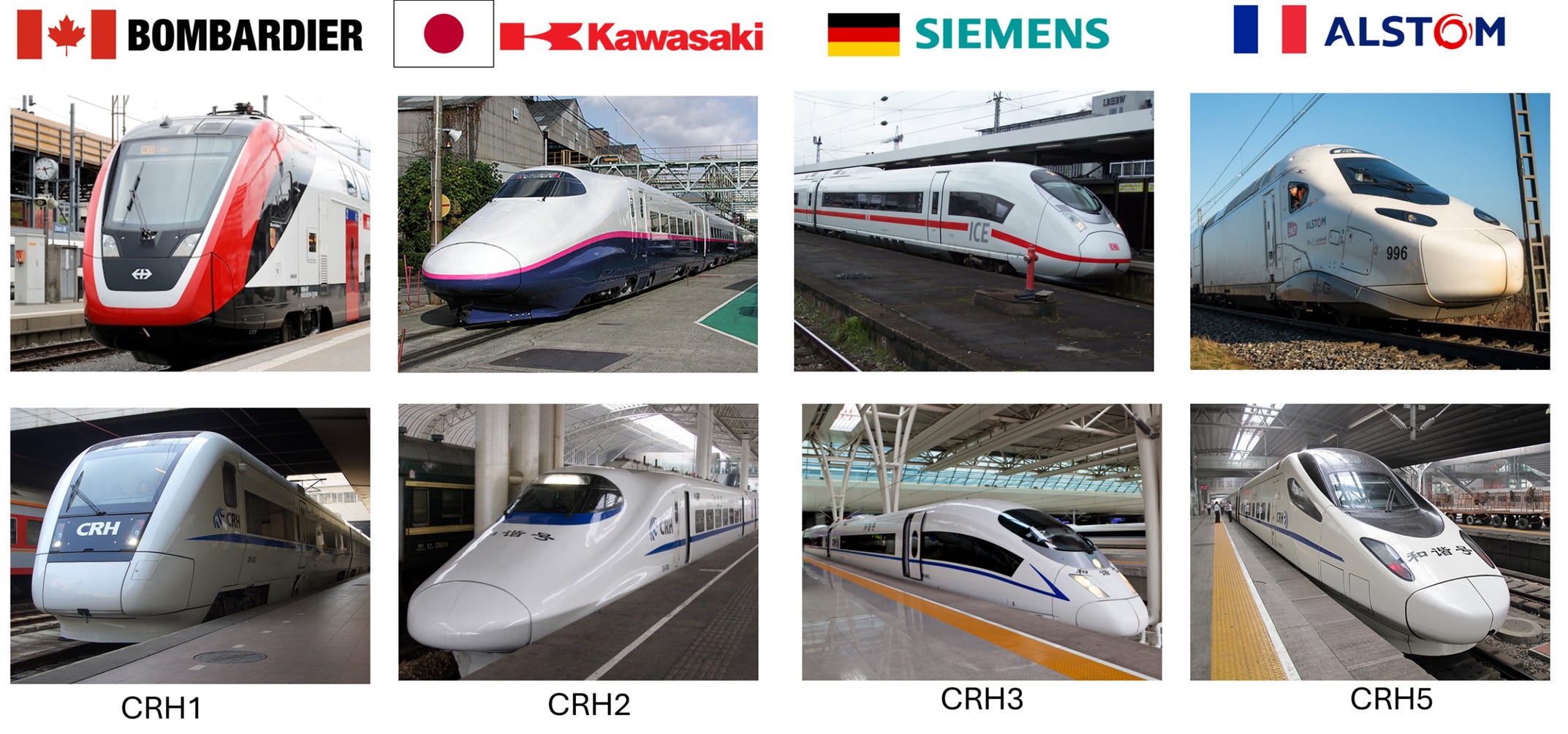

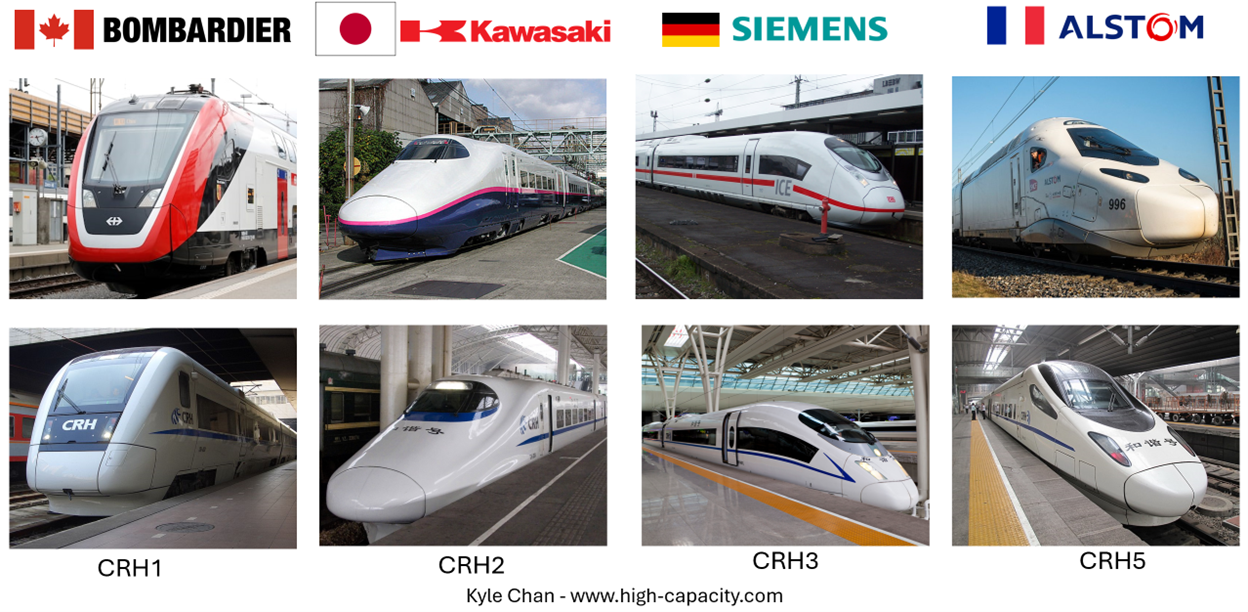

Take the case of high-speed trains, for example. When China was gearing up to build its first high-speed rail line from Beijing to Tianjin in 2004, China’s Ministry of Railways (now called China Railway) solicited bids from foreign train manufacturers, like Siemens and Alstom. These foreign trainmakers were facing mature markets at home with little potential for future growth. China’s pitch was simple: we’re about to pour unimaginable sums of money into building a national high-speed rail system—the foreign firms who help at this early stage will be well-positioned to get a piece of this potentially massive market.

The catch was that each foreign trainmaker had to form a joint venture with a Chinese firm and jointly produce trainsets in China. In the process, each foreign trainmaker agreed to transfer certain technology and manufacturing know-how to their Chinese partners. Of course, the Germans will say they never gave away their core technology, like the train control software. But it was the whole range of production-related knowledge that mattered, down to even the smallest technical skills like how to weld properly.

But does technology really get transferred in these kinds of partnerships? There’s strong evidence that it does. A recent study of China’s auto industry, where China also used this kind of “market access for technology” exchange, found that joint ventures with foreign automakers didn’t just improve Chinese-made cars. They improved each Chinese automaker’s cars in the areas where the foreign partner was strongest. Chinese automakers that partnered with Japanese brands tended to be more fuel-efficient. Chinese automakers that partnered with German brands tended to have stronger engine performance. Technology and know-how are a kind of DNA that gets passed down through these partnerships.

Going back to the high-speed trains, you can see the family resemblance in China’s early high-speed train models with their respective foreign JV partners in one of my all-time favorite slides I like to use in talks.

The puzzle for me is: why don’t all developing countries do this? China is unique in some important ways. Most countries don’t have such a giant domestic market to entice foreign firms with. Also, when the Chinese state says they’re going all-in on something as big as a national high-speed rail network, they really mean it—and foreign firms believe them. But there are some countries, like India, that might seem well-positioned to use this same strategy. Yet when I spoke with people familiar with India’s effort to build its first high-speed rail line, for example, they were frustrated that India didn’t do more to get technology and know-how from their Japanese partners.

2. “Bring in technology, absorb it, then re-innovate” (引进技术消化吸收再创新)

Getting the tech transfer process set up is one thing. But being able to truly understand the technology and build on top of it is another. This is where many countries run into trouble. They might lack the scientific and technical foundation—or the motivation—to really learn the technology at a deeper level.

In the case of China’s high-speed rail program, China didn’t just have existing domestic firms with experience in train manufacturing and railway construction. It also had research centers and national laboratories focused on the science and engineering of high-speed rail. During my fieldwork, I talked with researchers at Southwest Jiaotong University in Chengdu, which has several labs dedicated to research on core high-speed rail engineering problems like traction and suspension. These researchers often had expertise in related areas, such as aerodynamics and vibration control from the world of aerospace engineering.

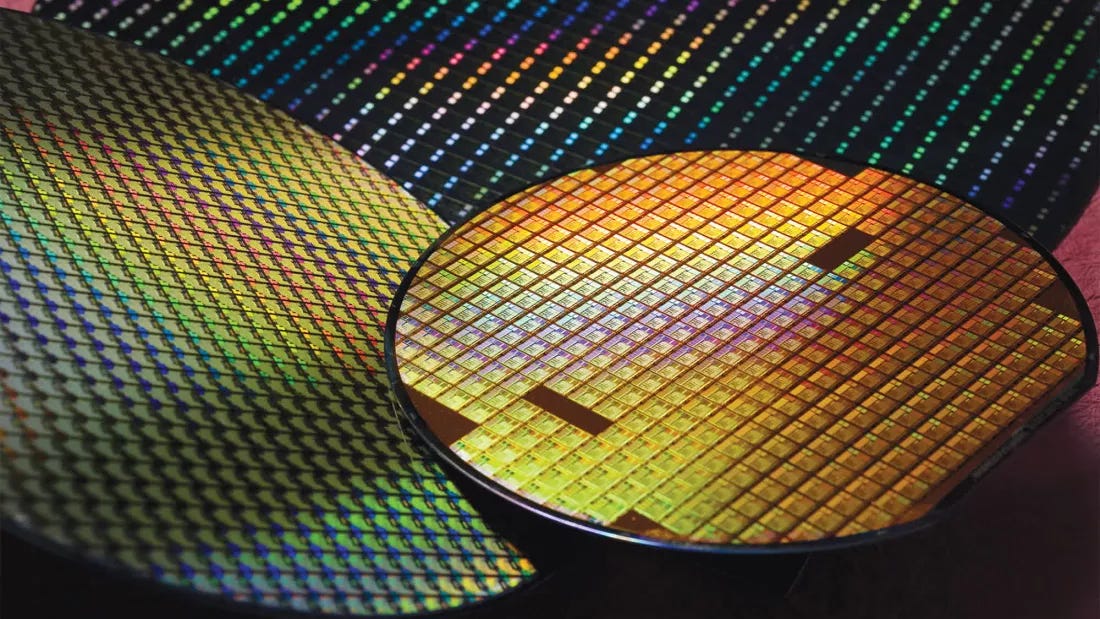

In the case of China’s solar industry, you have a long history of R&D on solar technology stretching back to the 1960s when Chinese researchers were trying to develop solar power for satellites at the Institute of Semiconductors, part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. When Chinese private firms started to enter the solar industry in force in the 2000s, they relied heavily on imported turnkey manufacturing equipment from countries like Germany. As they faced growing bottlenecks in the supply of polysilicon, the main ingredient for solar cells, China’s solar industry might’ve stalled. But instead, they were able to move up the value chain to more complex polysilicon production in part because China already had a scientific knowledge base in this area from trying to develop silicon wafers for semiconductor chips. Today, China dominates every stage of the solar manufacturing process.

Bring in global industry leaders. Use them to turbocharge your supply chain.

China has used this industrial playbook repeatedly. Bring in a foreign firm that’s an industry leader or pioneer, like Apple or Tesla. If you’re going to spread know-how to your own domestic firms, it might as well come from the best-in-class foreign firms. Give them generous inducements to come, like subsidies and land. Don’t be stingy—see this as a long-term investment in your broader economy. Do whatever it takes to make their Chinese factories a success, like helping to cut through red tape. Then push these foreign firms hard to develop your own domestic firms as suppliers.

This is what happened with Apple.

Zero corporate taxes and value-added taxes for 5 years

Creation of a special economic zone with special customs exemptions

Hundreds of millions of dollars to finance factory construction

Building housing for workers, then recruiting and training workers

Building infrastructure, like power generators, an airport expansion, and pipelines

Bonus payments for reaching export targets

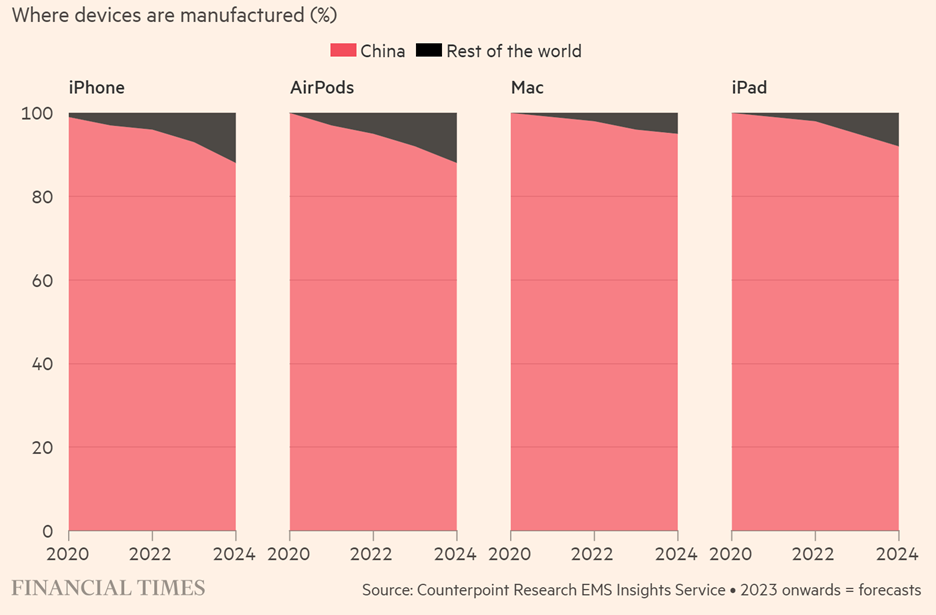

Today, over 90% of iPhones as well as most other Apple products are made in China. Apple executives work directly with Chinese suppliers, interrogating their CEOs and engineers to ensure sufficient technical capacity, then working with them to build specialized components at scale. Even when Apple sources from American, South Korean, and Japanese companies for their most valuable components, these are often manufactured by their factories in China. As one Apple executive put it:

“The entire supply chain is in China now. You need a thousand rubber gaskets? That’s the factory next door. You need a million screws? That factory is a block away. You need that screw made a little bit different? It will take three hours.”

Most importantly, this vast China-based smartphone manufacturing ecosystem enabled the rapid rise of homegrown Chinese smartphone brands, like Huawei, Xiaomi, Vivo, and Oppo, which now rank among the best-selling brands globally.

And this is what happened with Tesla.

China agreed to make special concessions to convince Tesla to build a plant in China. China changed its rules to allow the Shanghai Gigafactory to be a wholly foreign-owned subsidiary rather than a joint venture with a Chinese firm, as was previously required for all foreign automakers. China also changed its emissions regulations to allow Tesla to sell hundreds of millions of dollars of carbon credits to other automakers. Shanghai’s top leader at the time, Li Qiang, who is now China’s premier and number two leader, helped Tesla get over $1.5 billion in concessionary loans from Chinese state banks.

Local Shanghai officials fast-tracked the construction of the Shanghai Gigafactory, helping Tesla build the entire plant in under a year. To make it happen, they helped Tesla get land, environmental permits, and access to electricity. (Notice the combination of both national-level support and local government support in China.)

Tesla benefited enormously from its Shanghai Gigafactory, which now produces more than half of all Tesla vehicles and helped save the company from the verge of bankruptcy. But this deal also benefited China’s own domestic EV industry by building up Chinese suppliers, such as Chinese battery giant CATL.

The case of LK Group serves as a striking example. Tesla worked with LK Group, a Chinese maker of manufacturing equipment, to produce gigantic casting machines for what Tesla calls “gigacasting.” These casting machines allow Tesla to manufacture large auto components as a single continuous piece, which saves time, factory space, labor, and materials that would normally be needed to weld together many separate pieces. LK Group then went on to sell similar “gigacasting” machines to six Chinese firms, likely other automakers.

Today, 95% of the components used in Tesla’s Shanghai Gigafactory are from China, and Chinese firms make up almost 40% of Tesla’s global EV battery supply chain.

To be sure, the success of China’s EV industry today is due to a wide range of factors, including decades of supportive government policies and deep expertise in core battery technology. But Tesla’s plant in China helped to turbocharge its domestic industry, creating not only jobs for Chinese workers at the Shanghai Gigafactory but also an upgraded supplier ecosystem for China’s own homegrown EV brands. As reported in a recent New York Times piece:

“There’s Before Tesla and After Tesla,” said Michael Dunne, an auto consultant and a former General Motors executive in Asia, about the company’s effect on Chinese industry. “Tesla was the rainmaker.”

More reading:

“Quid Pro Quo, Knowledge Spillover, and Industrial Quality Upgrading: Evidence from the Chinese Auto Industry” by Jie Bai, Panle Jia Barwick, Shengmao Cao & Shanjun Li

This is the research study that looked at how Chinese automakers “inherited” the particular strengths of their foreign JV partners.

World Bank report on China’s High-Speed Rail Program

This is probably the single best overview of China’s high-speed rail program, which the World Bank played an instrumental role in.

“How China Built ‘iPhone City’ With Billions in Perks for Apple’s Partner” by David Barboza, New York Times

“In China, Tesla is a Catfish, and Turns Auto Companies into Sharks” by Li Yuan, New York Times

Thanks for reading High Capacity! Subscribe for free to receive new posts.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK