It’s Been 20 Years Since We Invaded Iraq. I Am Still in the Desert.

source link: https://humanparts.medium.com/its-been-20-years-since-we-invaded-iraq-i-am-still-in-the-desert-a10bd32d9b63

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

It’s Been 20 Years Since We Invaded Iraq. I Am Still in the Desert.

Even though many veterans came home physically from Iraq, we never fully returned home

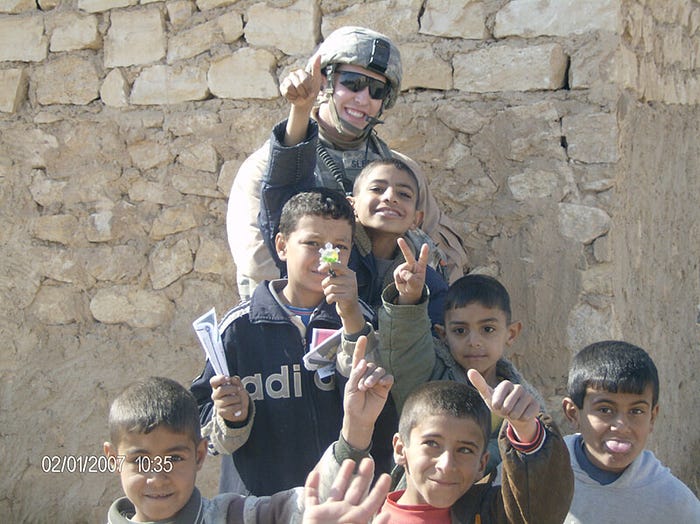

Photo of Author | Ramadi, Iraq 2006

“I have gone to war and now I can issue my complaint. I can sit on my porch and complain all day. And you must listen. Some of you will say to me: You signed the contract, you crying bitch, and you fought in a war because of your signature, no one held a gun to your head. This is true, but because I signed the contract and fulfilled my obligation to fight one of America’s wars, I am entitled to speak, to say, I belong to a fucked situation.”

— Anthony Swofford, Jarhead

Twenty years ago, I dug a hole at a fever pitch while on a beach in South Padre Island, Texas. It was a shallow hole, but enough to contain vomit full of beer and Lunchables that I’d deposited into the trench. After wiping my mouth and scooping sand over the puke, I stood triumphant and raised a fist to a chorus of cheers. I’d just beer-bonged three Miller Lites on a challenge.

For the uninitiated, beer bonging is when you pour beer into a funnel attached to a long piece of plastic tubing and then consume the alcohol as fast as possible. This process leaves you unbelievably drunk, but it’s a rite of passage among many college students. Granted, I couldn’t keep the liquid down, but the other college co-eds found the feat impressive.

A few months earlier, I’d returned from the military’s Defense Language Institute, where I’d picked up another language. In search of a break from college and military routine, I joined my brother and a group of friends for Spring Break. My brother was the first to greet me post vomit escapade and slapped my increasingly pink shoulder, then handed me an ice-cold beer. I gratefully accepted and rinsed my mouth with the cold liquid.

While swishing the beer around in my mouth, I observed a large rock wall in the distance with men and women strapped into harnesses, trying to climb it. Above the wall, an enormous flag bearing the words “U.S. Army” stretched taught due to the ocean breeze.

I gestured with my beer. “You think they actually get any recruits on spring break?”

Before my brother could answer, we watched a girl fall off the wall and swing midair in her harness. We laughed, but then noticed an eerie hush had fallen over the normally frenzied conversations on the beach.

“What’s going on?” I asked as whispers spread throughout the crowd. Ever since September 11, 2001, people had remained on high alert, thinking there might be another terrorist attack on U.S. soil. So my heart sank, fearing the worst once more.

“It’s Iraq!” someone yelled. “We’ve invaded Iraq!” Excited conversations broke out over the beach, and soon chants of “U-S-A!” roiled over the ocean breeze until they reached a crescendo. More beer was opened and fists raised defiantly in the air, as people remembered the fresh wound of the September 11 terrorist attacks.

I’d known since January 2003 we were invading Iraq. Half of my unit had received orders about the upcoming invasion, and the last time I’d been with them, the room had been electric with excitement. Standing on the beach and chugging beer while eying cute girls in bikinis made me feel ashamed. I was living it up, and they were on some convoy blitzkrieging their way through the desert.

I didn’t have to dwell on it for too long because three days later, I’d receive orders to head to war, too. Not Iraq, but Afghanistan. Iraq would happen three years after my beach escapes. I found it ironic that the sand on South Padre Island looked like sand in Iraq. The difference was everything buried within the sands of Iraq could kill you. Scorpions, chemical munitions leftover from the Iran-Iraq War, or never ending improvised explosive devices (IEDs) sought to claim soldier’s lives.

I’d spend fifteen months trying not to die within the city limits of Ramadi, Iraq, even getting shot at the day after Christmas 2006. When I came home, I swore to get on with my life. Turn the page. Never open the memory box of Iraq.

I wish that could have been true.

Mr. Ben?

As of this writing, the war in Iraq began two decades ago. As a man now in his forties with young children, my life differs from that of the grizzled sergeant who fought during the Surge and spent his youth in combat. I was a mere eighteen years old when I joined the Army and twenty-one the first time I went to war. By the time my 30th birthday approached, a horrifying epiphany hit that I’d known nothing but war throughout my twenties. I exited the Armed Forces after this revelation with no end in sight to the “Forever Wars.”

Not that the Iraq War is just some memory of a bygone time, however. On Sundays, I help teach Sunday School to fourth graders at my church. At the end, I pray for their requests, like doing well on a school test or healing for a broken arm. I try to relate to the kids, so I told the young girl who brought up the broken arm that I, too, had broken my arm.

“HOW!?” the fourth graders exclaimed in fascination. It was then I realized I’d made an egregious mistake, for I had to explain the wound came from an explosion overseas. Their interest peaked, the questions came in rapid fire succession. In these young children’s faces, I saw those of the Iraqi children. It is in these moments that you recall who you are and what you did to survive.

Photo courtesy of author

“SHOOT THE MOTHER FUCKER! DON’T LISTEN TO HIM!” I scream to the gunner in the turret. The argument raging inside our Humvee is whether we should kill the man holding a cell phone and peeking around a corner. Our lieutenant gives an order not to shoot, and a screaming match erupts. While I’m the senior ranking sergeant, he’s still in charge, but I’m worried about hitting an IED as the Battle of Ramadi rages. My other teammate is screaming too. “KILL HIM! KILL THAT FUCK!” There are Iraqi children playing in the ditches nearby as we shout at each other. I steal a glance at one of their faces while they laugh, oblivious to the surrounding war.

Then I’m back.

A fourth grader asks, “Mr. Ben?”

“You’ll learn about those wars in your history books,” I say, changing the subject. “Let’s get back to the lesson…”

I never wanted to be the veteran haunted by his past, but I suppose that’s what happens when you’re in the smallest minority in the United States. American Indian and Alaskan native make up 1.3% of the population, often considered the smallest US ethnic minority. LGBT identification is at 7.1%. By comparison, the Iraq and Afghan War veteran is only 0.86% of the US population. For twenty years, we held down the longest running wars in US history on back-to-back-to-back deployments. A bunch of old men and women who never served in the killing fields sent young men and women to die based on their political whims and foreign policy. Many got rich doing it while espousing platitudes about Iraqi freedom.

It’s a question I get asked often now. About the war, I mean. “Do you feel you fought for freedom?” Depending on what side of the aisle they lean politically, they’ll either ask with an air of smugness or concern. I don’t care how they lean, because the answer is the same for both: Yes. I do.

For nearly two decades, the American people were able to collectively ignore the horrors of war and bask in the blissful ignorance of never knowing death and destruction. There was no draft. The Bush and Obama administrations made sure the media didn’t air soldiers coming home in pine boxes. Everyone stateside got the freedom to be comfortable and indifferent, while less than 1% carried the embers. You can even say that you’re anti-war for all these reasons and more, but the veteran knows something you don’t — the government is not. If they need warm bodies for the meatgrinder, they will gladly take your sons and daughters should the situation become dire. Count your lucky stars that four different presidential administrations decided not to hand a rifle to your children and make them kill another human when they easily could have.

Please don’t misunderstand me. I am not mad or upset with the US population for these reasons. I believe most Americans recognize the harsh realities and what we did to our soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines. They grasp how the long years at war bruised our souls and have (for the most part) tried to be kind and supportive.

And yet, here I am, decades removed from Iraq, and still thinking about Iraq.

I am not some angry veteran, mad at the world around him because of the Iraq War. I’m happy. I have readjusted. But war carries consequences that many of us have permanently etched on our souls.

The most difficult truth to face when reflecting on the Iraq War is that a part of me will always remain in Iraq, even though I’m physically back home. It’s the part of me that was once a young, adrenaline-fueled soldier, exhilarated by the thrill of battle, gripping a rifle tightly, and scraping by just enough to survive another day. As an older man, I both cherish and detest this.

I suppose it’s why I can never escape the desert.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK