When Worlds Collide

source link: https://authoraimeeliu.medium.com/when-worlds-collide-1f821460dcc

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

When Worlds Collide

Wit, irony, and the imperial minister’s poignant gesture that helped forge my family

My grandfather Liu Chengyu was a scholar revolutionary bent on overthrowing China’s Qing (aka Ch’ing) Dynasty in the early 1900s. He was also a poet and author. Alas, in keeping with the custom of humility in Chinese culture, he wrote little directly about himself. His anecdotes instead relate to little-known twists in Chinese history and tales of his many friends, who ranged from notorious warlords to the leaders of the Chinese Revolution led by Dr. Sun Yatsen. Occasionally, though, he dropped personal details that have provided me with extraordinary insights into the history of my biracial family.

My grandfather published his anecdotes in the mid-1940s in books that I found in the East Asian collection of UCLA. I had to hire a scholar of classical Chinese to translate them for me, but once I could finally read his work, I understood the sense of kinship I’d long felt for this grandfather, who died in China the same year I was born in Connecticut.

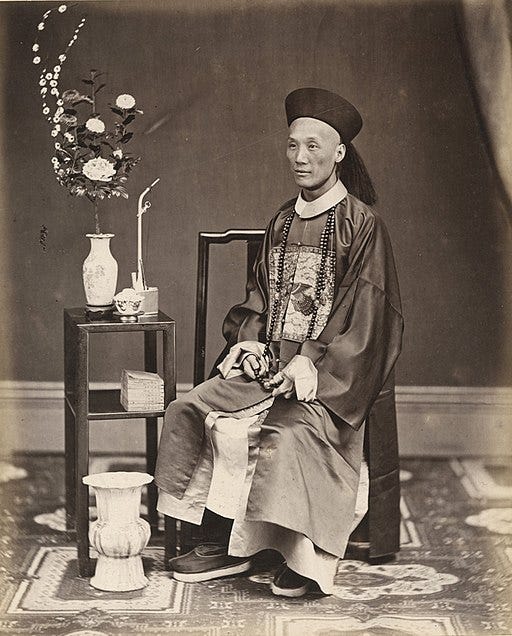

Called Papa in our family, my dad’s father was the only other writer in our family. His poetry is gorgeous, filled with meandering paths and mountain spirits, bridges beyond bridges, and mysterious gates into a world that seems to me as remote and inaccessible as the Middle Ages. He wrote with immediacy of this realm of emperors and palanquins, viceroys and concubines, because it was the world he knew best. His father, my great-grandfather, was an imperial magistrate. Yet Papa Liu Chengyu was determined to upend his known world to bring democracy to the Middle Kingdom.

The revolutionaries pull some strings

America must have seemed as alien to Papa as Imperial China seems to me, but he approached it as a fan. That’s what drew him to the man known as the Father of Modern China, Dr. Sun Yatsen. Papa wrote, “We believed the time had come to bring down China’s Ch’ing dynasty and replace it with a modern republic.” Like the United States.

Sun Yatsen appointed my grandfather to edit San Francisco Chinatown’s revolutionary newspaper, Ta Tung Daily. The paper’s agenda was to raise funds for rebel action from overseas Chinese — including the journeymen who had come to seek their fortune on “Gold Mountain” and wound up doing laundry and building railroads — in North and South America.

But The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was still in full effect, so the only way for Papa to enter the U.S. in 1903 was on a student visa. Dr. Sun arranged for his protégé to enroll at UC Berkeley. And Papa used his late father’s guanxi, or connections, to hoodwink the very regime he meant to overthrow — into paying his tuition:

I had a scholarship from the provincial government of Hupei to study at the University of California at Berkeley, which permitted me to stay in the United States.

Just as Papa straddled the line between China and America, he also straddled the line between his magistrate father’s official legacy and his own revolutionary ambitions. He played the gap, in other words, navigating the distance between worlds and historical moments, counting on that distance for protection.

There was a moment in 1905, however, when that distance collapsed on my grandfather, and his worlds collided. As he explained it, “five high-ranking officials from the Ch’ing court came to examine the West. One was Minister Tuan, who had been my teacher in Hupei.” Although Papa’s account makes no explicit mention of our family, I’ve come to realize that I might not be here today if Minister Tuan hadn’t made this visit.

Introducing my family’s secret godfather, Minister Tuan Fang

To my grandfather’s mortification, the chancellor at U.C. Berkeley invited his former teacher Tuan and his senior minister Tai to give a speech on campus during their stay in San Francisco. Of course, Papa was bound to attend.

Try to picture the dank and creaky university hall, rows of gawking American students stuffed into starched shirts and woolen waistcoats. The mutton-chopped chancellor drones a polite introduction, as if these foreign “dignitaries” have nothing to do with the “Celestials” that the majority of racist San Franciscans were then hell bent on exterminating. And when the chancellor finally finishes his remarks, he invites his guests to approach the lectern. They bid each other forward, one more resplendent than the other in turquoise and magenta silk gowns, their backward hats trailing bright red tassels and peacock feathers. “Like costumes in a Pingju opera,” according to my grandfather.

Then, for my grandfather, the fun begins:

Tuan said to Tai: “As senior, you please speak.”

Then Tai said to Tuan: “You have had experience with Westerners and know their etiquette, you please speak.”

So Tuan spoke a line, but after it was translated, Tuan asked Tai: “Is that correct?” And Tai said: “Yes, yes.”

Then Tuan spoke another line, and asked Tai again: “Is that correct?” And Tai again said: “Yes, yes.”

In the entire speech there were several hundred lines. Tuan asked Tai the same question several hundred times, and Tai replied the same.

An American classmate said to me: “When we give a speech in Europe and America, only one person talks. When you Chinese give a speech, two people speak. Can you tell me the reason?”

I composed a reply: “This is China’s ancient code of respect. In cases of important ceremonies, the junior speaks and the elder supervises. These two were showing the utmost reverence to the university, in accord with China’s most ancient etiquette.”

The classmate relayed my fabrication to the chancellor, and in a long letter afterward the chancellor thanked the two ministers.

It’s the humor that impresses me. Papa’s timing reminds me of Abbott and Costello. But as he well knew, the ministers’ paralyzing insecurity reflected the paralysis gripping the dynasty they represented. And that my grandfather would help to topple just six years later.

Several days after this performance, Papa was working at his Chinatown newspaper office when an emissary from the Chinese consulate appeared.

Panting and sweaty from the climb up four flights of rickety stairs, this fat man told Papa:

“Mr. Tuan said that you are his student. All his other students from Hupei came to see him. He sent me to bring you over.”

I said: “I am busy with the newspaper, please allow me to come in a few days.”

He said: “There is a carriage waiting at the door. I cannot return empty-handed.”

I still needed to arrange the copy for the next edition. So the consular official sat. Two hours later I finished and we rode together.

At the consulate Tuan introduced me to Tai, saying: “This is my student Liu Chengyu.”

Tai asked, “On what ancient text was your explanation to the chancellor based?”

I answered with utmost seriousness: “This is what is called diplomatic rhetoric.”

This would be relayed around Chinatown as most marvelous words. Both ministers smiled.

Then Minister Tuan came to the point: “Before I came to San Francisco, I read your articles in the TaTung Daily. Let me say to you, after today don’t say those things anymore.”

I replied: “I don’t know what things you mean.”

He said: “Those things you say.”

I said: “I didn’t say anything.”

He said: “I mean the things that you say every day.”

I said: “I don’t say anything every day.”

Tuan said: “You don’t know yourself? Those things that come out of your own mouth. You know. I know. After today, don’t say them. We are all Chinese, and should deal with foreigners in concert.”

I did not reply. It was plain to see that I had chosen foreign dress over imperial robes. Minister Tuan was my teacher, but he served my enemy.

He said, “When we return from this trip, there will be a big advantage for you. Brother, don’t say those things.”

I stood to leave. Then Tuan begged: “I am your teacher. You are my student. Give me some face. Don’t say those things anymore.”

The way Papa dances verbal circles around these two, no wonder imperial China was in decline! And yet, my grandfather doesn’t gloat. His wit is threaded taut with compassion.

Humanity blooms amid tragedy and change

Papa still had a toe in the old world, whether he liked it or not, and he was decent enough to acknowledge that connection in his tale of Minister Tuan. My grandfather honored his teacher. He owed him. But how could he promise not to champion the cause he was now dedicating his life to? He managed to demur, but that is far from the end of this story:

Tuan and Tai left for Europe, and a few months later the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire destroyed the Ta Tung newspaper offices along with the rest of Chinatown.

Tuan, who was still traveling in Europe, sent me five hundred dollars of his own money along with a telegram that he had received from Hupei. The telegram said: “As for Liu’s scholarship fund, it has been cut off because he belongs to the rebel party.”

Poor Tuan. His travels ultimately converted him. When he returned to Peking from his inspections in Europe and America, he spoke out: “The constitutional system of Europe and America really makes ruler and people one body without any separation. Whether ruler or president, when reporters interview them, they can take photographs any time they want. This is the spirit of rule by law. China should learn from it.”

Tuan’s constitutional spirit brought him a charge of “gross disrespect” and impeachment from the court. I might have suggested some more diplomatic rhetoric to save his face. Alas, he did not consult me.

Minister Tuan’s kindness to his radicalized student is all the more remarkable for his own perilous political position. As a palace official, he was not allowed to display the slightest disloyalty to China’s imperial rulers. A gift of $500, equivalent to $16,000 today, paid to a young rebel like my grandfather could have cost Tuan his head. But whether out of personal empathy, a sense of duty, or his own premonition that the Qing Dynasty was destined to fall, the gentle minister sent that extraordinary gift , and it changed my family’s destiny.

A $500 wedding?

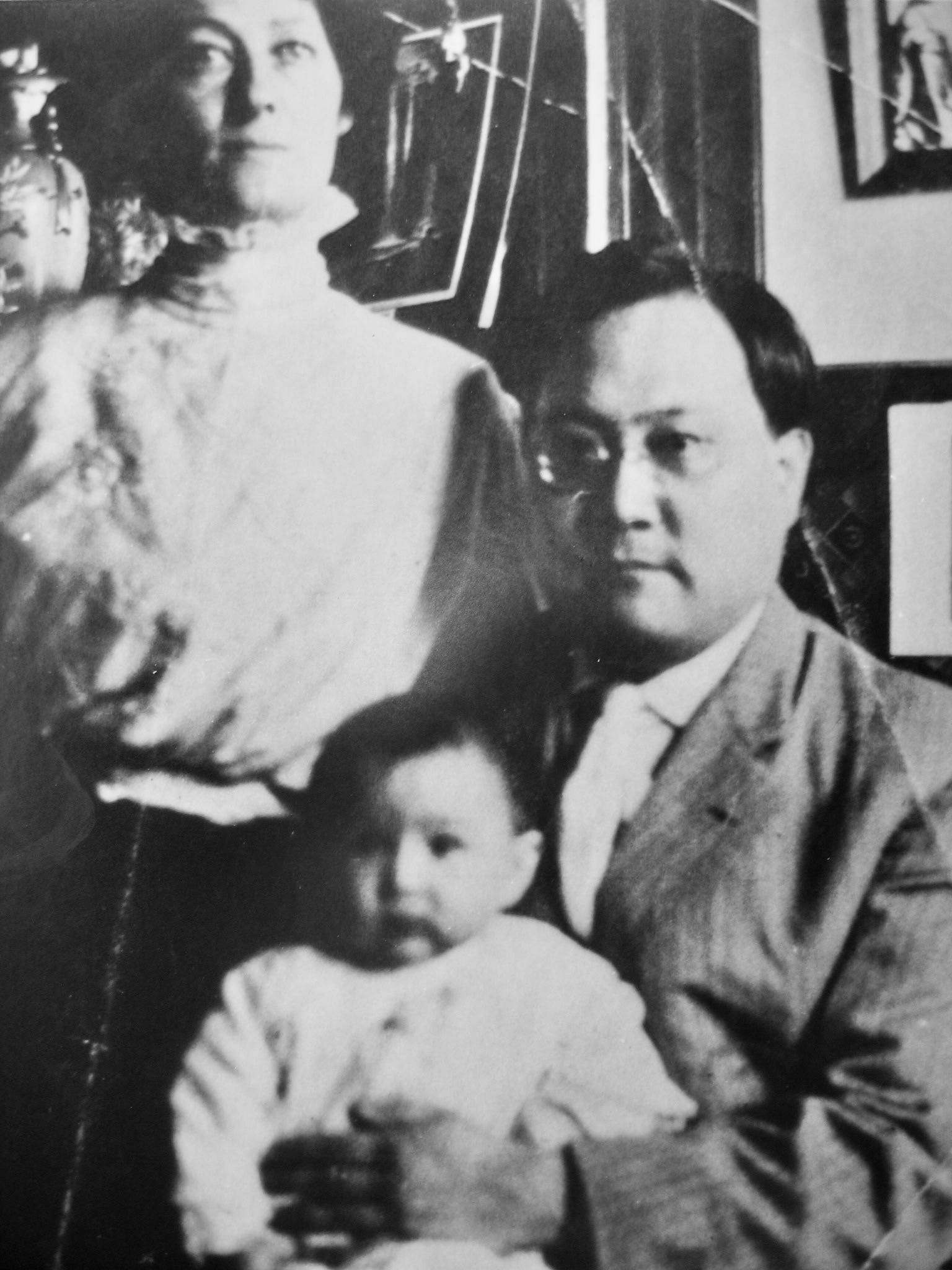

For the Great San Francisco Earthquake and Fire had destroyed not only my grandfather’s office but his home and, for several months, his livelihood. Stripped of his scholarship funds, he’d have been penniless if not for his former teacher’s charity. Moreover, he’d have been useless to his English tutor, the single young American woman who would become my grandmother.

No one in my family knows if romance was brewing between my grandparents before the catastrophe, but lore has it that my grandmother’s boarding house on the edge of Chinatown went up in flames after the quake, and my grandfather came to her rescue. He continued to protect her in the tent city that was erected for quake refugees in the Presidio.

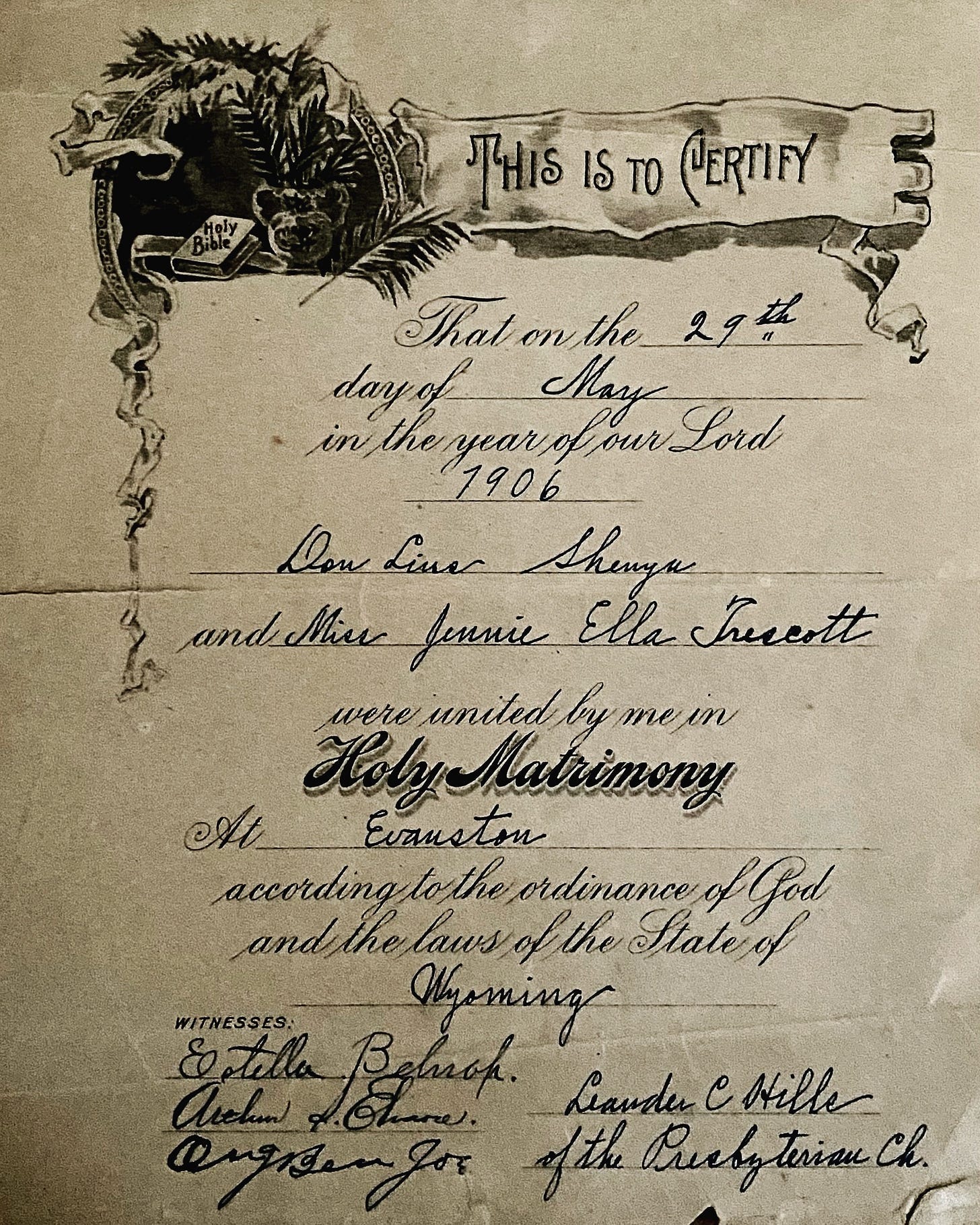

Unfortunately, there’s no specific mention of their marriage in Papa’s memoir, but the calendar tells its own story. The Great Quake occurred on April 18, 1906. My Chinese grandfather married my American grandmother just six weeks later, on May 29: less than a month after Minister Tuan sent his generous telegram with $500.

It seems clear to me that without the minister’s intended earthquake relief and consolation gift, my grandparents never would have been able to marry. On top of everything else they faced, anti-miscegenation laws throughout the west prohibited their biracial union, so they had to travel across three states to Wyoming before they could find a minister willing to certify their marriage. By unwittingly funding this long journey, Minister Tuan helped lay the foundation for our family.

That train trip, a whole other saga, formed the basis for my grandparents’ 30 years together in America and China and inspired my novel Cloud Mountain. You can read more recently discovered tidbits about my grandparents’ “sensational” wedding odyssey here:

Aimee Liu is the author of four novels, six nonfiction titles, and too many ghostwritten bestsellers to reveal. Her latest novel is Glorious Boy.

Visit her website at aimeeliu.net. And if you’re interested in family history and memoir writing, check out her new Substack newsletter, Legacy & Lore.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK