E-bike fires: Why low-quality lithium-ion batteries explode, and why NYC is stru...

source link: https://slate.com/business/2023/02/e-bike-fires-batteries-lithium-ion-explode-new-york-city-delivery-workers.html

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

What It Takes for an E-Bike Battery to Explode

And why the threat is so hard for cities to stop.

Feb 20, 20235:45 AM

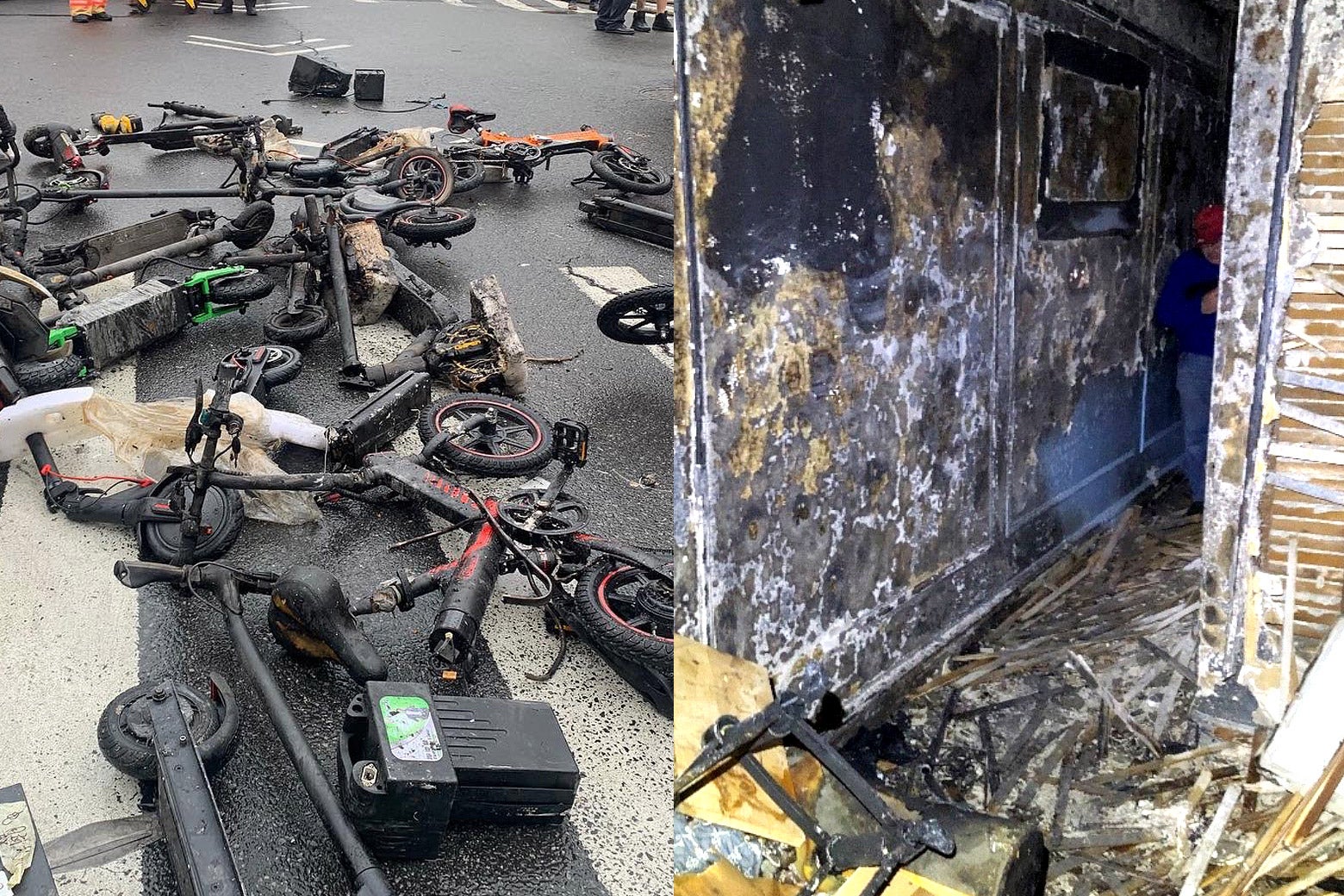

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos via FDNY/Twitter.

Every day, Manny Ramirez crisscrosses Manhattan, ferrying takeout food, toiletries, and a host of other things that people order on apps. Instead of driving a car, which would be too expensive and is too slow in traffic anyway, he racks up 90 to 100 miles a day on a bike. When he started as a full-time delivery worker, he used a regular one, powered by his legs. “It’s horrible,” he said. “I felt on the first days, my legs were horrible.”

So, like thousands of other delivery workers, Ramirez switched to an e-bike, powered by a lithium-ion battery. It turns an exhausting job into one Ramirez enjoys.

But using these batteries during the day means that Ramirez has to recharge them at home overnight. And certain lithium-ion batteries can be dangerous, depending on how they are handled and whether they’re built to industry safety standards. If they fail to keep the energy inside under control, they can erupt in a tremendous burst of flame and toxic gas.

New York City is seeing an alarming number of battery fires, spiking from 22 in 2020 to 104 in 2021 to 216 by the end of last year. They killed six people last year, up from four in 2021. With its high concentration of delivery workers and other people using bikes to get around, New York has had more of these fires than anywhere else in the country, but the fires are increasingly a problem in many other cities, too. A growing number of fire departments are warning of the risks of batteries that are damaged or modified, or that were not built to meet safety standards.

Only some lithium-ion batteries pose a danger. Undamaged, unmodified batteries that meet certification standards set by UL Solutions—such as the ones in Teslas and cellphones and those used by bike-share programs like Citi Bike in New York—are widely regarded as safe. Citi Bike has thousands of e-bikes, and the New York City Fire Department says it hasn’t had any fire issues with those bikes. If you bought an e-bike from a reputable retailer and your battery has the UL marking, you can breathe easy.

The problem is that as the popularity of e-bikes soars, more and more people are relying on batteries without protections. They’re doing it for good reason, many of them say. But those batteries can still lead to disaster.

One of New York’s battery deaths happened about a year ago in a public housing tower in Manhattan’s East Village. The fire started when a battery burst into flames in a bedroom a little after 7 a.m. on Dec. 16, 2021, killing one person in the room. Two teenagers in the apartment’s other bedroom later told investigators they heard an explosion, and the wall between the rooms collapsed. They tried to escape out the door, but the fire was already too intense. So they scrambled out their fourth-floor window as smoke billowed out over their heads.

Bystander videos showed what happened next. As neighbors yelled, “Don’t do it!” the teens clung to the windowsill, seemingly unsure of where to go. Then they reached for a pipe running along the building’s exterior, escaping just in time—moments later, flames shot out the window they had just been in. They shimmied down the four stories to the ground.

When lithium-ion batteries fail, they fail horrifically and without warning. “It’s almost like a blowtorch effect that results from the failure, where we see immediate flames in all directions,” FDNY’s chief fire marshal, Daniel Flynn, told me. The flames quickly reach temperatures above 1,000 degrees. Anything combustible nearby will catch fire. The battery cannot be extinguished with water or foam or any regular firefighting material. It just has to burn itself out.

With the number of fires rising so quickly, it’s clear there is a problem. But no one can agree on what to do about it. Ban e-bike batteries from apartment buildings? Restrict sales of certain kinds of batteries? Build a whole new network of recharging stations? There are competing ideas, and legislation from local politicians, making the rounds. But until one of them wins out, the fires will only continue.

Ramirez has never had a battery fire, and he doesn’t worry about one breaking out in the apartment he shares with his family, even though he brings his batteries inside and recharges them overnight. He gets batteries from a store he trusts and said he avoids the riskier types: those that are damaged, repaired, or modified. “I always make sure the batteries are new, new, new,” he said.

But he isn’t buying the ones most recreational e-bike riders have—because he said that would prevent him from doing his job. All the same, some lawmakers want to ban sales of noncertified batteries. A bill introduced in the New York City Council would make it illegal to sell batteries that have not been labeled by UL or a similar testing lab.

But the delivery workers say they can’t get by with only those batteries. The UL-certified batteries, they argue, just don’t have the power to carry them through their day. “They are smaller and they last less,” said Hildalyn Colón-Hernández, director of policy and strategic partnership at Los Deliveristas Unidos, an advocacy group for New York City’s delivery workers. The certified batteries last three hours, she said, which would require workers to lug around as many as four batteries per shift.

The certified batteries often have less energy because of a key difference in what’s inside. Lithium-ion battery packs are made up of dozens of cells, each roughly the size of a AA battery. The cells are packed closely together. But the electrodes in each cell have to be kept apart. If they come into contact with one another, they can short-circuit, said K.M. Abraham, an expert on lithium-ion batteries and a research professor at the Northeastern University Center for Renewable Energy Technologies. “And when that happens, all of the energy stored in the battery is released very quickly,” he said. The process is called a “thermal runaway”—the battery violently unleashing massive amounts of energy—and it’s the cause of New York’s deadly battery fires.

So it’s critical to keep the negative and positive electrodes in the cells from touching. For this, manufacturers include a material called a “separator” between the electrodes in each cell; batteries that satisfy UL standards have separators that meet certain thickness, stability, and performance requirements.

But some manufacturers, Abraham explained, “use very thin separators, much thinner than what UL recommends, because if very thin separators are used, more electrodes can be fit in the extra space to provide higher capacity.” With the thinner separators, “the cells have a much higher chance of having some safety hazards due to physical touching of electrodes,” he said. Thicker separators are less likely to develop holes or other defects that could lead to short circuits and thermal runaways. But thicker separators also take up more space, leaving less room in the battery for the electrodes, so the battery stores less energy.

Workers say they need that extra energy. To those riders, UL-certified batteries “are too weak for us because our bikes are heavy,” Ramirez said. The certified batteries are good for recreational use, when riders use their bikes for only a few hours and don’t push them very hard, he told me. “They’re not for work.”

And work is getting more demanding. Delivery workers say they have to push their bikes harder than ever before because the delivery apps keep giving them larger geographic areas to cover. We “have to run longer distances for the same or less money, so we have to be faster than before,” Ramirez said.

Years ago, most delivery workers would work for a restaurant and have to cover only that business’ delivery area. But now, with most working for delivery apps, they can find themselves going anywhere. Ramirez said he starts most days around 110th Street and Broadway in upper Manhattan but often ends up covering the whole island. Once a delivery takes him to one area, the next pickup may start there and take him somewhere else. With 30 to 35 deliveries each shift, he often reaches 100 miles.

Some city officials aren’t convinced that the workers’ jobs require higher-energy batteries. “Weighing the cause and effect of a longer-lasting battery versus a battery that will save lives, the choice is clear. You want a battery that will not combust,” said council member Joann Ariola, who is sponsoring the bill to ban sales of uncertified batteries.

Mike Monaco, a co-host of the Hazmat Guys podcast, is an expert on fires involving hazardous materials. He told me he understood the workers’ concerns about certified batteries running out of energy too quickly. But the uncertified batteries are risker. “I would be hesitant to want to bet my life on them,” he said. “And that’s what you’re asking people to do.”

Fires caused by these batteries get serious fast. With a normal fire, according to Flynn, the city’s chief fire marshal, the fire department will get a call about smoke in a building, arrive at the scene, and find a fire that is just starting to develop. But with battery fires, he said, “we go from no problem whatsoever to a fully involved fire. If there are any combustibles around that bike, they will be on fire in a second.” When firefighters arrive, “they encounter a fire that’s already in its advanced stages.”

At the fire in Manhattan that forced two teenagers to climb down the side of a building, the teens told investigators that the fire began so quickly, it sounded like an explosion. “They attempted to exit the room through the door, but due to fire and high heat they were forced to exit through the window,” an FDNY report stated. It said there were usually two e-bikes that were recharged in the bedroom next to the teens’ room.

In October, another lithium-ion battery fire in Manhattan led to a similarly daring escape, with a woman dangling from a 20-story window until firefighters could perform a rope rescue to bring her to safety. The fire injured dozens of people.

Once a battery goes into thermal runaway, there is essentially no way to stop it. “It’s not possible to put out one of these fires,” said Monaco, who has also worked in FDNY’s HazMat Company 1 for 18 years. Firefighters on the scene will focus on isolating the battery, often by putting it in a bathtub filled with water. “That’s not going to prevent thermal runaway. That’s going to prevent propagation. Most of the time, in the shower area, there are not a lot of other materials around,” Monaco said.

And the danger isn’t just from the flames—it also comes from gases the battery releases. “The toxic gases are pretty significant. They come on fast; they come on overwhelming. They can quickly overwhelm an apartment with toxic, flammable gases,” he said.

It is not clear how many of New York’s battery fires have been caused by batteries belonging to delivery workers rather than batteries belonging to other people who have e-bikes, mopeds, or scooters. The workers I spoke to said no one they knew had experienced a battery fire. A spokeswoman for the FDNY declined to give the profession of anyone associated with the battery fires.

Delivery workers are wary of being made into scapegoats. New York City did not legalize e-bikes until 2020, and the workers still have fresh memories of police confiscating bikes and arresting workers, preventing them from earning a living. Now restrictions on batteries could pose another threat to their livelihoods, and they worry that new rules will be imposed before the threat of battery fires is fully understood.

“There is a rush to judgment,” Colón-Hernández said, and “a rush to make bills about things we do not know about.” She pointed to a rule proposed last summer by the New York City Housing Authority that would have entirely banned storing or charging e-bikes in public housing. After an outcry, NYCHA quietly tabled the proposal. A NYCHA spokeswoman declined to answer questions about the proposal but provided a statement saying that “at this time, there is no new rule in place” and that NYCHA is “meeting with experts and stakeholders to determine the best course of action moving forward.”

Other proposals would avoid bans on batteries. Some advocates have floated the idea of a government subsidy to help workers pay for certified batteries, which, at about $900 each, are 50 percent more expensive than the batteries they typically buy. But the city government doesn’t have much appetite for the idea—“I don’t think the city is going to subsidize,” said council member Gale Brewer, who has been working with the Deliveristas and others to try to find solutions. Even if it did, helping workers to pay for the certified batteries would still mean workers have to carry around more batteries to do their jobs, adding weight and taking up space on their bikes.

One bill Brewer is sponsoring would ban the sale of “second-use” batteries, which are assembled from parts of used batteries.

Another idea would help the workers keep their current batteries but charge them in a safer way, outside their apartments. In October, lawmakers announced a program to convert abandoned newsstands to recharging stations across the city, starting with a large newsstand in lower Manhattan. Brewer said that with the initial $1 million in federal funding allocated to the project, she expects three stations will be built.

The charging station will also give workers a place to rest between deliveries. The idea for the site came from Gustavo Ajche, a delivery worker who helped found Los Deliveristas Unidos. “We have to bring solutions, not restrictions. We are doing essential work for the city. We are doing our best to help the city,” he said. “To me, this is part of the solution.”

Other parts of the solution include public education.

Any battery, whether certified or not, that has been damaged or modified is unsafe, Flynn said. “Any defect or damage to your battery, you need to get a new one,” he said. “It is not designed to be repaired.”

He also warned against using a charger that was not designed for the battery, or buying batteries from secondhand stores. “We’ve seen people actually making these batteries in their apartments,” he said.

Fires happen most often when the battery is recharging, so it is important not to recharge the device where it might block an escape, like next to the front door. In some of New York’s deadly fires, people were trapped in their apartments because of where the battery was placed. “I don’t recommend charging them inside,” Monaco, the hazmat expert, said, “but if you do, be really, really smart about how you do it”—don’t leave it next to a fire exit or in a bedroom.

Ajche and Ramirez said that experienced delivery workers know to avoid repaired or knockoff batteries. “We take care of our batteries because we know that getting something cheap, it’s not safe,” Ajche said.

“I never repair batteries,” Ramirez said. “If one is not working properly, I just buy another one.” With those precautions, he said, he feels comfortable using his noncertified batteries.

Newer workers, or those trying to make do on tighter budgets, might not realize the risks. “If you go on the marketplace on Facebook, you see people selling cheap stuff, cheap batteries. So that’s the problem,” Ajche said. “Sometimes they catch fire. It’s not good.”

Flynn said public education is critical to solving the problem. “We all know propane is dangerous, we all know torches are dangerous, so we treat them as such. But I don’t think people realize lithium-ion batteries are dangerous,” he said.

Just what to do about the more dangerous of the lithium-ion batteries, though, remains in dispute. With all the legislative proposals still only proposals, the Deliveristas have succeeded—for now—in avoiding bans on the noncertified batteries that workers use. The workers are excited about New York’s recharging stations, and say a network of stations around the city could make things safer for everyone. But it’s unclear whether a system like that would be enough to stop the fires, or if New York City is in for more tragedy.

</div

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK