Five Mildly Anti-Buddhist Essays

source link: https://sashachapin.substack.com/p/five-mildly-anti-buddhist-essays

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Five Mildly Anti-Buddhist Essays

some grunts at a meme cloud

Buddhism is often treated with special regard, as if it is a superior philosophy that correctly identifies the source of all human misery, and correctly lays out the path to its elimination.

I disagree with this characterization. Buddhism definitely has a lot going for it. Its tradition contains significant innovations in contemplative practice, beautiful poetry, wonderful art, and a lot of insight about the human condition. I have benefited much from its fruits, and so have many. But it also contains some real duds. I believe that Buddhism should be used as a source of inspiration and challenge, but that it has significant flaws that are under-discussed.

Sasha's 'Newsletter' is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Be Your Own Buddha

Here’s why we should respect Buddhist tradition over other religious traditions, and regard it as uniquely compatible with modernity. The Buddha, unlike other religious prophets, was an empirically-minded, rational human being—a scientist of the mind, who was just trying to figure out how everyone could be happy.

Just kidding. That’s a modern revision of history, sometimes called Buddhist Modernism. In truth, Buddhism is an ancient religion with mythology and symbolism that is not at all science-y, from a cultural context that is highly non-Western, with elements that do not gel with modern sensibilities. For example, a major element of the original Buddhist scriptures is life-denying, anti-emotional asceticism.

Does that not sound Buddhist to you? Did you think Buddhism was the religion of flourishing and positivity? Well, here is the Buddha, excoriating a monk who broke his vow of celibacy: “Worthless man, it would be better that your penis be stuck into the mouth of a poisonous snake than into a woman’s vagina.” And here is the Buddha on whether you should be resentful if you’re being dismembered: “Monks, even if bandits were to savagely sever you, limb by limb, with a double-handled saw, even then, whoever of you harbors ill will at heart would not be upholding my Teaching.”

Moreover, the Buddha of scripture was a fantastical and bizarre character, as you would expect from ancient mythology. Some sources have the Buddha being born from his mother’s side after she was stabbed by the tusk of a white elephant in a dream. Some traditions have him being born with special physical attributes, like a cranial protuberance and unusual tufts of hair. And, outside of such legends, there is no secular history of Buddha the person—very little is known about the “historical” Siddhartha Gautama. It is possible that he didn’t exist.

Also, the modern focus on meditation is, well, modern—a result of Buddhism finding purchase in the psychology-loving West as a sort of innovative lifestyle choice. Most lay Buddhists of history did not engage in meditation.

But, okay. Let’s go ahead and decide that the Buddha was a scientist of the mind, and that psychological intervention is the point. If we interpret his life story in that way and ignore the stuff we find weird, here is what we find. The Buddha was a disagreeable maniac. He left a rich household and a beautiful wife so that he could find the answer to human suffering. To do this, he studied all the best psychotechnologies of his day, and found none of them satisfactory, eventually settling on his own blend, which he taught far and wide.

If the conclusion you take from this story is that you should be Buddhist, you are absolutely missing the point. The point is that we should experiment with everything and pick what best fits our situation, reverence be damned. There is no reason to believe that traditional Buddhist psychological theory and practice should be given ultimate preference, unless you believe that there have been no new psychological insights or useful tools created in the last millennium. Moreover, though any reader of Ecclesiastes can tell you that the human condition is, in some ways, strikingly unchanged, we also certainly have modern neuroses—bugs in our cultural programming that bear no resemblance to those of the nobility of the Himalayas of yore. Maybe we need some different tools for those.

This is where the informed observer might pipe up and mention that Buddhist tradition makes similar noises. There is the wonderful Zen saying by the wonderful teacher Linji: “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.” And the Kalama Sutra, in which the Buddha says: “Come, Kalamas. Do not go upon what has been acquired by repeated hearing; nor upon tradition; nor upon rumor; nor upon what is in a scripture; nor upon surmise; nor upon an axiom; nor upon specious reasoning; nor upon a bias towards a notion that has been pondered over; nor upon another's seeming ability; nor upon the consideration, 'The monk is our teacher.’"

This is a creditable sentiment. But you usually hear it as part of an introduction to yet another Buddhist book explaining why Buddhism is the greatest. If Buddhists engage in some facsimile of self-skepticism and emerge with the conclusion that Buddhism is essentially correct, and don’t mention that Buddhism has some rather large limitations, I will be skeptical of the fierceness of their self-skepticism.

Don’t Grasp at Grasping

Let us try to steelman the Buddhist psychology of suffering, and see where it can take us.

The translation of the basic Buddhist doctrine that most people hear is something like this. “Life is basically mostly suffering, the cause of suffering is desire, lower your amount of desire by doing Buddhist-approved activities.” This is obviously false. Luckily, it’s probably not an accurate translation—it would be weird if such a storied tradition were that stupid. Another potential translation is something like this: “A lot of life is a bummer because of this gross dissatisfaction we feel. The cause of this is a mental tendency we could call grasping or fixation or resistance. Or tanha, if we’re sticking to the original Sanskrit—which means “thirst,” referring, metaphorically, to the desperate thirst of human clinginess. The answer to this is Buddhist-approved activities, like refraining from being an asshole, having a non-harmful livelihood, and meditation.”

I think this is true to a profound degree, and that this is a crown jewel of Buddhism as a psychological teaching. Grasping really is responsible for a lot of our misery.

Grasping is one of those mental activities that is so universal that it’s hard to spot unless it’s pointed out to us. It is the mind’s habit of clamping down forcefully and ineffectively on reality in the insane hope that this will make things different. Rather than being an emotion or thought unto itself, it is a sort of distortionary style that is overlaid on emotions or thoughts.

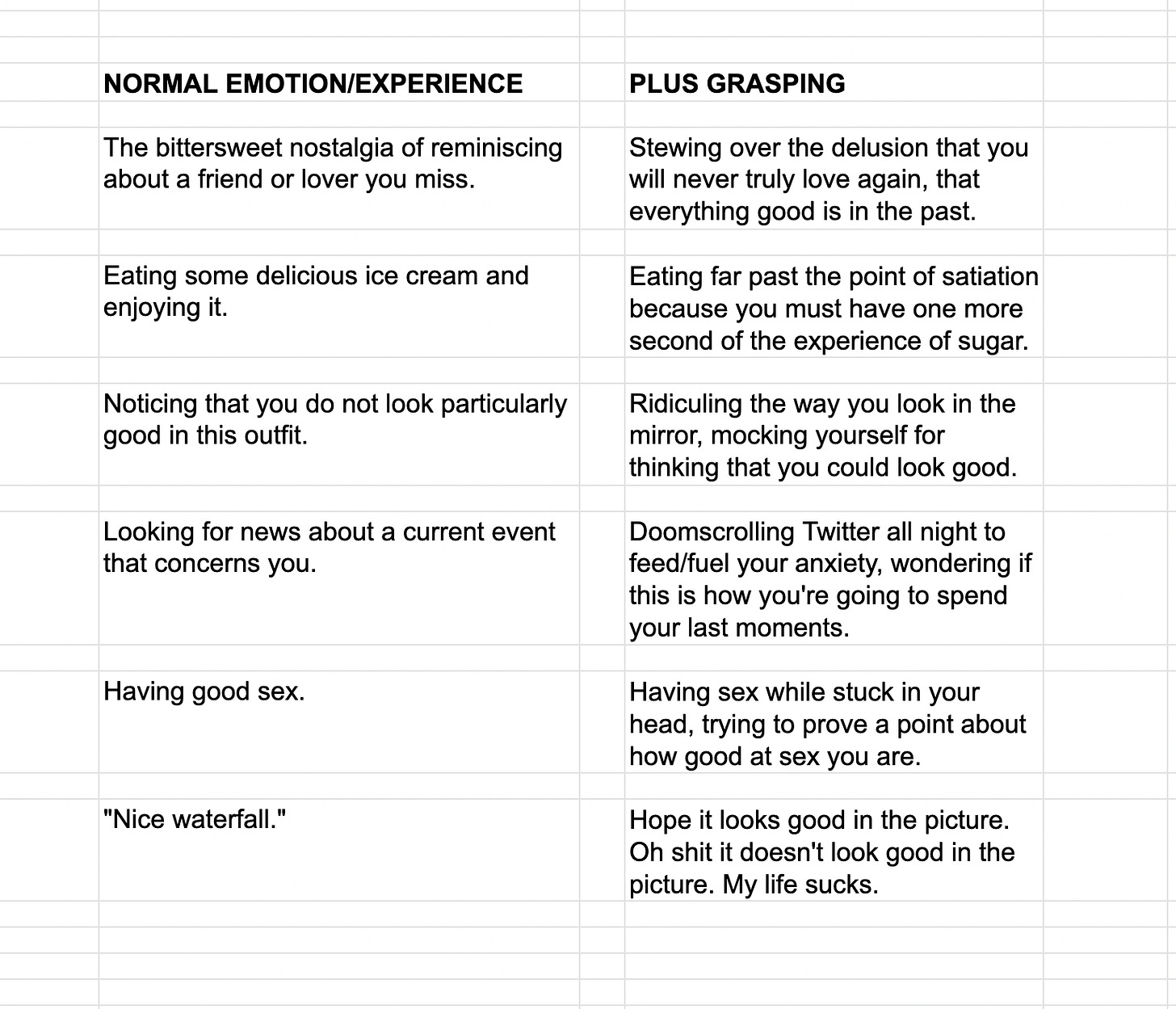

The easiest way to define grasping, probably, is to list a series of experiential states that are nice or tolerable, and show how much worse they become when grasping is added.

So grasping is bad. It’s what makes bad things feel like forever, and good things feel like not enough. It’s what makes everyday, tolerable life seem like an intolerable problem, even when things are going well.

And, as Buddhism promises, meditation—along with leading a reasonably non-destructive lifestyle—can ease grasping by huge amounts. With a little mindfulness practice, you can often learn to disempower the squirmy thoughts that are grasping’s hallmark. This is pretty cool. With more meditation practice, something even cooler can happen—you can learn to perceive the infinitesimal mental motions that compose grasping, and, in the process, gain the ability to stop a large amount of mental grasping before it starts. This is really cool, and it’s a mental experience I’m glad to have enjoyed—here is a fumbling attempt at describing it.

When you do that, does it end all of your suffering? Does life become perfect? Is this what we should spend all of our time on?

Frustratingly, the answer to these questions turns out to be “yes and no.”

Personally, after years of going down the meditative path, life is enormously nicer, but the problems of existence are far from over. I am still capable of making bad decisions that hurt myself and others. I am still capable of wasting my potential and making myself miserable.

And this is not just true of me. There is a dirty secret that basically everyone who spends time with meditation communities finds out. Which is this: people who let go of grasping as completely as you can—like, famous meditation teachers, or practitioners who have been at it for decades—still have problems. They are still neurotic and prideful. They still stress out about their social media accounts. They still engage in immoral behavior. While they might not report as much subjective suffering, they still act out in ways that objectively belie insecurity and dissatisfaction.

In fact, some seem more neurotic than average people. You would not believe the internet flamewars some purported gurus will get into over who is really enlightened and who is teaching correctly. And this might have something to do with the inherently problematic aspects of identifying with a certain set of mental states. You will obviously run into trouble if you brand yourself as Mentally Perfect in some way. Like, if you’ve become highly invested in the idea that you’re not supposed to experience mental turbulence anymore, this will naturally cause you to avoid stress and conflict, which could, in turn, cause you to avoid growth, accountability, and humility.

Now, that doesn’t have to be a big deal—it’s fine to still be neurotic. Two things, though. First, some meditators claim that meditation is the cure for human psychology, in so many words, and this is obviously incorrect. Second, it’s worth keeping in mind that, reducing your personal suffering, if treated as the primary goal of life, can just become another individualist cul de sac. You can end up in Athletic Buddhism, where the point is to be the most spacey/intense person in your area code. A nice corrective is Ken Wilber’s formulation, Grow Up, Clean Up, Wake Up, and Show Up—look at your darkness, live responsibly, touch the numinous with practice, do good shit in the world. Spiritual practice is the “wake up” part, and it is integral, but only one quarter of the program.

(Hilariously enough, Buddhist tradition is filled with admonitions about the potential peril of identifying with certain mental states, and then some Buddhists will turn around and go into detail about the superheroic mental qualities that an Enlightened Person has, or how you should worship your teacher as a perfect being, etcetera.)

Spiritual practice can make us much happier and somewhat less fucked up, but we are all, always, somewhat fucked up. Everyone has a shadow side. The best we can do is place ourselves in circumstances that channel our less savory impulses towards the least destructive ends possible. It is always a trap to believe that you’ve perfected your psychology.

We go to meditation for relief, consolation, and wonder. But then what comes after? I would suggest that if your long-term contemplative life does not demonstrably cash out in some degree of increased behavioral nobility, then what you have is a talent for mental masturbation. And that’s ultimately not so bad! Some people spend their whole lives fucking other people over. Sitting quietly in private rapture is significantly better than that. But I believe there is more to aspire to.

Buddhism Has No Essential Self

In the first section, I mentioned that the psychological, secular view of Buddhism is a modern invention and that the Buddhist tradition began with a life-hating asceticism. Now, in this section, I will admit that this was unfair—there are traditions that are not quite so renunciative. In fact, Buddhism has a million different traditions, many of which completely disagree with each other. Buddhism makes Christianity look positively homogenous.

This tweet, seemingly hyperbolic, appears to be literally true.

Do you think Buddhism is about finding virtue in this life, or escaping resurrection by meditating away your karma? Then you will be surprised that perhaps the most popular form of Buddhism in East Asia is, essentially, about praying and going to a kind of Buddhist heaven, the Pure Land. It’s actually a kind of pre-heaven: in the Pure Land, you can study with Amitābha Buddha and get enlightened. (He’s a different Buddha. Did you think there was just one Buddha?)

Do you think Buddhism is about charity and goodwill? I can see why you’d think that—Buddhists do seem nice. Well, hilariously enough, most Buddhist alms were just indulgences, merit bought by giving money to monastics; traditionally, Buddhism is not the religion of widespread social justice. Except for some modern traditions!

Do you think Buddhism is about using the intricacies of thicc meditation manuals to get yourself enlightened, combined with the original teachings of the Pali canon? Well, then spend some time with Zen teachers, whose instructions consist of extremely simple meditation, brain-melting riddles, and the sayings of their own lineage.

Do you think Buddhism is about being tranquil and sweet? You will be surprised by Tantric practices that involve stomping and yelling and channeling your wrath. Do you think Buddhism is about dissolving the illusory nature of self and sitting in a unitive state of Big Mind forever? My favorite Buddhist meditation teacher of the last century ended up advocating a practice of living through self-generated mythology, as much Jungian as Buddhist.

And it’s great that Buddhist tradition is so varied! There’s a lot to draw from. But also: when you praise Buddhism, just which one do you mean? And do you really understand that tradition? I think I’m a fan of the version of Vajrayana Buddhism David Chapman extols. If I had a Vajrayana teacher, there’s a small possibility I’d be writing an essay about how it’s superior to all of the other Buddhisms, instead of this essay. But I don’t have a Vajrayana teacher, so I’m not really sure I understand it or practice it, in any real sense. I guess I’m a David Chapmanist.

I think most Western people who say they’re Buddhist are following the Salad Bar tradition. They are choosing the bits of whatever tradition seems appealing to them, or they’ve read a Pema Chödrön book. This is ultimately fine, of course, and I highly recommend Pema Chödrön books. But that makes Buddhism kind of a meaningless label. You’re just saying “as the Buddha said,” or “it’s sort of a Buddhist thing,” and then saying truisms. Do you need to go looking for an ancient Asian stamp of authority to put on what you already believe anyway?

However. My friend Jake, reading this section, correctly pointed out that I am engaging in Salad Bar Criticism. People who like Buddhism point at some areas of the giant Buddhist meme cloud—the giant mass of traditions, observations, and modern derivations—and nod approvingly. I am pointing at other areas of the giant Buddhist meme cloud and making grunting noises. I can only hope that some of us are learning something along the way.

The Giant Hole in the Middle of Buddhist Teaching

There is a giant hole in the middle of Buddhist contemplative teachings. This is the disinclination to engage with mental content. Much of the time, modern meditators are taught to disregard their thoughts and emotions during meditation, to see them as stories without consequence that come and go1.

This can be a really nice practice. It yields important insights: that often your thoughts are insane, and that you don’t have to believe them. It is a solid correction to the default of treating all your self-criticism and worry as gospel.

However, as a default meditative stance, it is an overcorrection. First of all, it can lead to, essentially, a scolding relationship with the mind, in which you dismiss all of your desires and fantasies as undesirable “ego mind.” (I have been there. It is horrible.) Secondly, it can promote a self-effacing agenda in meditation, in which the goal is to erase your personality—and those who hang around in meditation circles will know that this is a common failure mode. Thirdly, it overlooks a powerful option: engage with your stories.

Treating your thoughts as unreliable doesn’t mean you have to disregard them. You could, instead, treat them as partial reports from different segments of your personality, which might not hold the whole truth, but might have valid concerns and intuitions. For example: instead of ignoring your inner shit-talking about an acquaintance who is a status symbol, you could compassionately take this as a signal that part of you has status anxiety, and then address that anxiety actively.

This is the view taken by modern meditation-influenced therapies like Internal Family Systems. And it is an extremely powerful way of interfacing with yourself, which can lead to psychological clarity, well-being, and even the type of mystical experiences told of by meditation specialists.

In my case, I meditated intensely for years in my twenties, along Buddhist guidelines, and it had a neutral or negative effect on my mental health. I ignored my shameful thoughts, but they just came back, or grew more powerful when I let them mutate in darkness. Then, a few years ago, I started using introspective techniques and engaged with my self-hatred directly. This lead to an incredible increase in my mental clarity and overall well-being, which, funnily enough, made gainful meditation practice possible for me for the first time.

This appears to be a widespread phenomenon. Since I began writing about this in public, I’ve heard the same story from many other meditators—that emotional processing techniques like Internal Family Systems, sometimes in combination with psychedelic medicine, lead to the improvements in inner life that meditation had promised them, and made contemplative practice come alive for the first time.

To their credit, some Buddhist teachers have definitely noticed this deficit. Hence the Big Mind Process, which is a self-dialogue technique with Zen aesthetics, or Feeding Demons, which is a therapeutic visualization technique based on ancient Tibetan practices, in which you confront your challenging emotions in the form of imaginary monsters. While we’re at it, Already Free is a great book advocating for using experiential psychotherapy techniques and Buddhist-influenced awareness practices as complementary opposites.

But the standard frontline meditation advice is still to ignore your thoughts and leave it at that. I think it’s tragically incomplete advice. I think an intro to Internal Family Systems would do a lot more, for most people, than standard vipassana instruction or a Goenka retreat.

Yay, Desire

Even though a lot of modern Western Buddhism isn’t quite as renunciative as what we find in the sutras, it is still kind of… bland2.The overall mood is still one of quietude, simplicity, and withdrawal. The classic imported Buddhist teacher style is to speak slowly and deliberately. The chanting is slow and even. Most meditation is stationary. Mindfulness is the focus, rather than, say, the raucous celebration. And a lot of the instruction is about what not to do, what desires not to have, what words not to say—it is a negative project, in the sense of being more about removing badness than adding something else. This is probably due to it being an attempt to turn an old conservative religion into a darling of the most vaguely stated kind of modern liberalism.

Aesthetics matter. The aesthetic of modern Buddhism gives you the impression that being nice, quiet, and simple is the way to be, that this is Buddhist-ish living. And, sure, some simplicity can be a nice recipe to the “frenzied pace of modern life.” But I dislike it as a binding ideal.

In our society, most of us have vast powers of individual agency. We can all do weird, wonderful, and terrible things in this technologically-enabled, interconnected, freely navigable time. And, on average, we squander that agency. Instead of doing the most with our gifts, we naturally fall into a kind of quiescence—the harried, cheap quiescence of a million notifications and an infinite supply of gossip. Somewhere in us, we crave striving. But we watch others strive instead.

Withdrawal and indifference don’t need to be encouraged in a post-digital consumer world. That is what is supplied to us by default. Intensity and difference need to be encouraged—genuine striving and passion. The courage to love fragile transient things, to form deep attachments and let them sculpt and wound you. Desire for stasis and placation is the default. Desire for something more meaningful is the relatively unsung alternative.

Spiritual practice can reduce your normal boring suffering. One great thing you can do with that is replace it with suffering of a more vibrant flavor.

This piece was much improved by notes from Cate Hall and Jake Orthwein. Jake does not necessarily endorse this piece.

Sasha's 'Newsletter' is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I am aware that analytical meditation exists in some Buddhist traditions, as well as meditating on emotion. For every Buddhism there is an equal and opposite &c

For an alternative, shout-out to Ikkyu’s poetry, and this kind of thing.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK