“How do I solve an ‘impossible’ problem?”

source link: https://uxdesign.cc/how-do-i-solve-an-impossible-problem-b2ddf93ee107

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

“How do I solve an ‘impossible’ problem?”

Have you ever felt incredibly overwhelmed when either tasked with or forced to deal with a problem in your life that seemed impossible to solve?

What if it meant the difference between life and death?

There’s a famous scene in the movie Apollo 13 that ends with Flight Director Gene Kranz saying to the team, “Failure is not an option.”

Based on a true story, it was supposed to be NASA’s third mission to land on the moon; however, just two days into the mission an explosion caused two oxygen tanks to fail in the service module. Cue Tom Hanks, playing astronaut Jim Lovell, reporting back to Mission Control in this famous scene, saying, “Houston, we have a problem”.

NASA very quickly needed to shift gears from trying to land the crew on the moon to getting them home safely.

Astronauts Lovell, John Swigert, and Fred Haise were forced to move to the lunar module in order to return to Earth — a use case it was not designed for. They would have a limited window to survive before they would be inundated with carbon dioxide, as the air scrubbers were only meant to filter enough of the gas to keep 2 astronauts alive in the module for a limited time.

Getting home safely was a problem that seemed impossible to solve.

As a product manager, I’ve worked almost predominately on moonshot types of projects — types of projects that have lofty goals, that no one has done before, and that involve a lot of unknowns. While not life-and-death scenarios for the most part, I’ve seen a lot of patterns emerge.

Here is an 8-step framework I have developed for how to approach solving problems that seem “impossible” to solve.

1) Find the problem

Maybe you’ve already been handed a really tough problem to solve. Maybe you’ve waded into one and it hasn’t been fully defined. In either case, it’s really important to start by asking really basic questions like:

- What is the problem?

- Why is it a problem?

- How big of a problem is it?

It sounds so simple yet so many teams don’t start here and when they end up with a solution that’s not great, when they look back often these questions were never answered.

There is a quote that I LOVE from Steve Jobs that has really stuck with me: “Everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you. And you can change it, you can influence it. Once you learn that, you’ll never be the same again.”

To address problem finding in a tangible way, I’ve put together:

2) Frame the problem

Albert Einstein once said, “If I were given one hour to save the planet, I would spend 59 minutes defining the problem and one minute resolving it.”

After a problem is found, too many teams make the mistake of jumping right in to trying to solve it vs. defining it first.

Problems can be defined by asking questions to understand and challenge constraints and to conduct pre-mortems to understand all the things that could possibly go wrong along the way so that a plan can be in place to prevent those things from happening. Questions like:

- What does solving this problem mean?

- Who are we solving this problem for, specifically?

- Why should WE solve this problem?

- What are the guardrails (knowns)?

- What are the unknowns?

- What are the biggest risks of solving this problem?

- What are all the things that could go wrong if we try to solve this problem?

- How can we plan to avoid these things?

3) Establish a unique, shared vision

Clearly articulate THE WHY of what you are trying to do in a narrative way: What is your North Star? Your purpose? What is the team’s why? What does the team believe in? What does the team do and why do they want to do it every day? What is the thing the team is trying to achieve and why is that a good thing to try to achieve? What problem is it solving? What is the value of achieving it?

Some examples from large well-known teams are:

- NASA: “To advance and communicate scientific knowledge and understanding of the Earth, the solar system, and the universe.”

- Google: “To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

- LinkedIn: “To connect the world’s professionals to make them more productive and successful.”

Each individual on a team should be able to repeat the team’s purpose verbatim, and the answer should be the same across the board — not just repeated but embodied. Everything that any individual on the team does should relate directly to this higher purpose.

4) Light the way

Outline a path by creating a tangible, realistic, and honest roadmap. Provide the team with guardrails to light the way and the steps needed to be taken along the journey will help to align all of the granular details of the team’s efforts.

As a leader, it is YOUR JOB to orchestrate and connect the dots — to set a clear goal and path to get there but NOT define the how for the team.

- What is the path?

- What will it take to get there?

- What are the key challenges the team needs to overcome?

- How can the team learn as quickly as possible to turn the unknowns into knowns?

- What is the bar for performance?

To me, I think of it a lot like planning for a trip. To be successful and work as a cohesive unit, leaders also need to arm a team with:

- A clearly defined goal — where are we going? What’s the destination

- Resources available — how much money do we have for this trip?

- Time frame — When will we be leaving and coming home? Why does this make sense for our trip?

It’s ok if you don’t know everything. Be honest and objective — identify what you don’t know and figure out what is required to help learn those things. Own the learning.

5) Create an environment where everyone can be themselves

5 years ago it was princess week at a dance school in North Carolina and all of the dancers dressed up like their favourite princesses. But Ainsley on the left decided to dress up as a hot dog. When asked why, she responded, “Because it’s my favourite costume”.

Be a hotdog if you need to be a hotdog.

Create the right environment for both individuals and the team as a whole to perform optimally and constantly improve — where team members feel safe physically, mentally, and emotionally. Lead with empathy and openness to create an environment where everyone feels like they can be the best versions of themselves.

Bring your authentic, weird self to the table to let others know that this is accepted.

What can help make those around you feel more comfortable to just be themselves?

- Ask questions instead of making assumptions

- Actively make team members feel included and recognize individual contributions

- Use language that is inclusive and approaches everyone on the same level

- Set up 1:1 meetings to better understand how team members are feeling and what their challenges are

- Listen while others are speaking

- Be open to having the tough conversations that need to be had in an objective way

6) Build a team that sees the world from many different perspectives

The best solutions come from cross-functional thinking and diverse perspectives. The goal of the team should be to move collectively as one vs. a handful of individuals.

- Prioritize recruiting for character over talent.

- Bring in broad level thinkers, deep experts, and stitchers — the people who connect the dots. Most teams are missing stitchers.

- Do regular, open assessments of the strengths and weaknesses of the team (like Debriefs and Retrospectives)

- Give team members guidance on a defined problem to solve but not HOW to solve it.

7) Have a clear and transparent decision-making framework

This helps to leverage the collective intelligence of the team, build trust, keep team members aligned to the greater objectives, and helps to foster better individual decision-making abilities that are in line with the team’s objectives.

When decisions are being made, context is key. The WHY and the WHAT should be thoroughly understood before approaching the HOW.

Avoid silos.

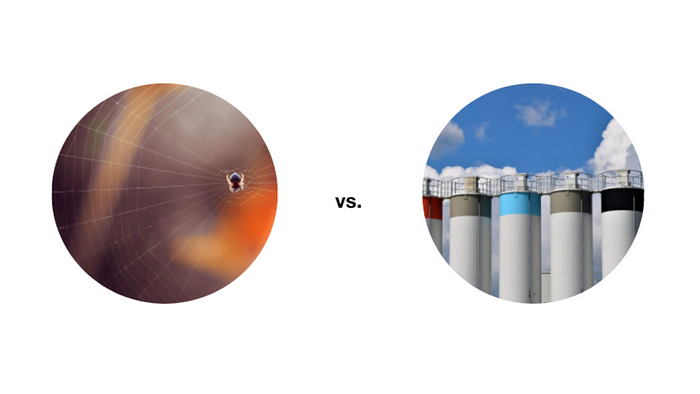

I like to think of the ideal structure to work together as a team like a web, with the deep experts building the web, leaders/decision makers in the middle with the broadest view of things who decide where the web should go, and stitchers being the go-between.

It is the responsibility of the deep experts building the web to do the absolute best job they can do to inform decision-makers, and it is the responsibility of decision-makers to leverage the information that exists within the broader team to make the best, holistic decisions.

8) Ignite a shared belief

Create emotional and data-driven sparks on an ongoing basis to ignite:

- Individual team members’ belief in themselves

- Team members’ shared belief in the abilities of the team as a whole

- The team’s belief in the possibility of achieving the goal

This can be done by making the WHY explicitly clear, using storytelling as a tool to spark emotional connections, being vulnerable and showing that you are also, in fact, human, and being transparent — using the facts to inspire, avoiding sugar coating and avoiding salesy-BS.

So how does this apply to the Apollo 13 mission?

Before Gene Kranz addresses the team after the oxygen tanks are damaged he has a thorough understanding of the root cause of the problem and a clear and transparent decision-making framework is in place.

He picks up a piece of chalk, walks up to the chalkboard, and both frames the problem and articulates the vision — Apollo 13 needs to circle the moon and slingshot back to Earth within a timeframe that allows the crew to survive. He clearly defines the goal and the timeframe the team has to achieve this goal, in probably the most tangible way I have ever seen.

The problem is framed very well — there is a scene where the engineering team is dumping what looks like random supplies onto a table. They are all of the resources the astronauts have on board with them to repair the damaged CO2 filter. This gives the team a tangible understanding of the constraints of the problem they are being asked to solve.

While there is major room for improvement on the diversity and inclusion front, Gene Kranz leans on his team, who are empowered to challenge constraints and focus on the basics — even if this means making a CO2 filter out of the cover of the flight plan and duct tape.

But the single most important factor in the mission being a success and the astronauts surviving?

The entire team had a shared, unshakeable belief that it was possible, even though it had never been done before.

I would love to hear your thoughts — drop a comment below or connect with me on Twitter👇

Lisa ✨

-Creator of Conscious Product Development

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK