Tools for Thought as Cultural Practices, not Computational Objects

source link: https://maggieappleton.com/tools-for-thought

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

budding

Tools for Thought as Cultural Practices, not Computational Objects

On seeing tools for thought through a historical and anthropological lens

Table of Contents

People familiar with the tools for thought, personal knowledge management, and "note-taking" space / twitterverse

If you prefer video, you can jump to a

of this essay from the May 2022 Tools for Thought Rocks meetupThe term tools for thought has become a new rallying point over the last few years. People who might otherwise gather around keywords like personal knowledge management (PKM), note-taking, networked thought, computer-supported collaborative work (CSCW), knowledge graphs, or human-computer interaction (HCI), are reframing their work.

There are

and research groups and thought leaders and

. But more than anything, people are using the term to describe a new class of software. Tools for thought is now a category tag in the databases of venture capital firms. The phrase appears on the landing page of every hot new knowledge management app:

Muse App

Anytype.io

Roam Research

Kosmik App

Even when it doesn't appear verbatim, we can see it in the subtext. These tools are here to help you “think better,” and “achieve more”.

Reflect App

Clover App

These software apps appear to have a clear vision of what a "tool for thought" is. It appears to involve writing notes, connecting them to one another, exploring dynamic views, and then experiencing a kind of emergent wisdom. An enchanting promise.

Yet there's something paradoxical here; the phrase itself and the way we're collectively using it feel misaligned. Taken at face value, the phrase tool for thought doesn't have the word 'computer' or 'digital' anywhere in it. It suggests nothing about software systems or interfaces. It's simply meant to refer to tools that help humans think thoughts; potentially new, different, and better kinds of thoughts than we currently think.

While this might seem like a dumb rhetorical question, what does any of this have to do with computers?

I think it's a question worth answering explicitly and comprehensively. If only to make clear to ourselves why we currently consider apps that allow you to link notes together the epitome of a tool for thought.

What is a tool for thought?

We're a bit too early in the establishment of this concept for anyone to have written a canonical definition yet. And like all significantly complex ideas, any proposed ones will be contested and controversial.

We can, however, get a rough estimation by looking at descriptions from some of the key texts we pass around the community. A tool for thought is...

“A context in which the user can have new kinds of thought, thoughts that were formerly impossible for them”

Andy Matuschak & Michael Neilson – How can we develop transformative tools for thought? (2019)

“A means of increasing the capability of a man to approach a complex problem situation, gain comprehension to suit his particular needs, and to derive solutions to problems.”

Douglas Englebart – Augmenting Human Intellect (1962)

“A truly new medium [where] the very use of it would change the thought patterns of an entire civilization”

Alan Kay – User Interface: A Personal View (1989)

Looking a these, it's easy to think of plenty of examples from human history of tools for thought that fit the bill. Here's a brief list:

Written language – 3200 BCE

Hard to overstate this one. Allows us to precisely record and communicate our ideas across vast amounts of time and areas of space. Both to ourselves and to others.

A cuneiform tablet – the earliest form of writing

Drawing – ~73,000 years ago

Drawing feels so fundamental it's hard to think about it as a tool people developed. But at some point, a person painted the first animal on a cave wall. Since then it's been one of the primary ways we represent thought and communicate meaning through spatial relationships and symbols. It did all the heavy lifting before written language emerged.

Bison paintings in the Cave of Altamira in Spain

Maps – 700 BCE

Visual maps showing routes through landscapes and layouts of cities enabled us to form mental models of physical spaces we had never been to or seen with our own eyes. They shift us from an “egocentric” view of the world to an “allocentric” bird's eye view. Take a look at Barbara Tversky's

for more on visual explanations and maps as tools for thought.Oldest known map of the world; carved into a Babylonian clay tablet

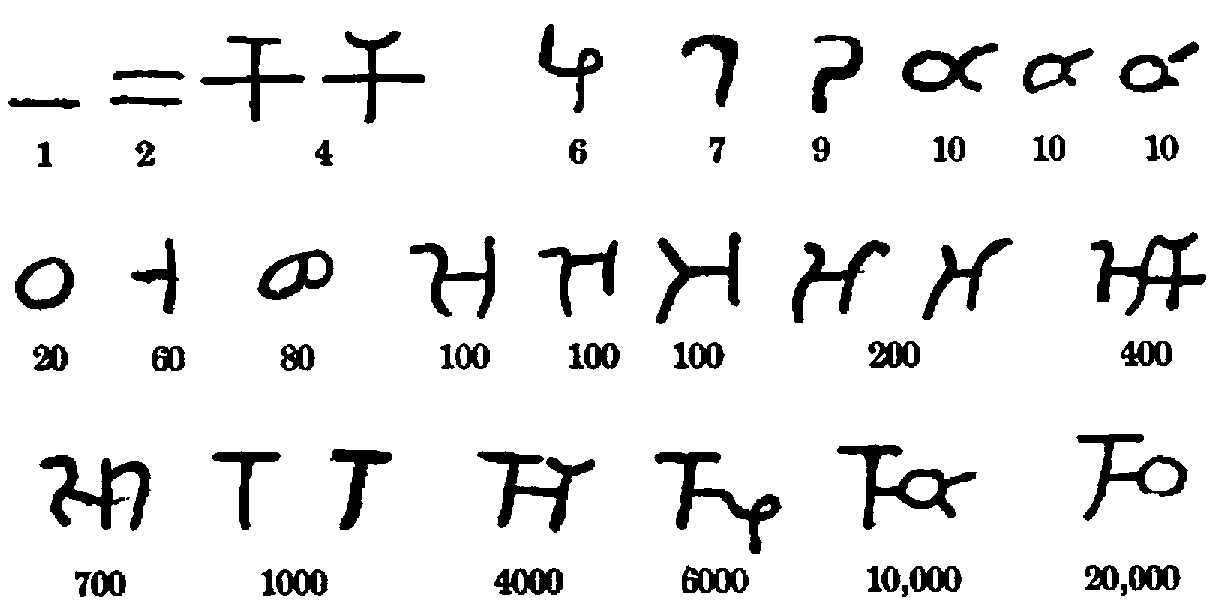

Hindu-arabic numerals – 400 BCE

The 0-9 numerals we use for all numerical notation. Allows us to switch to calculating on paper rather than using an abacus. Enabled us to store, share, reference, and calculate precise amounts. Great for record keeping and bureaucracy.

Early notational symbols found in southern India

Epic poetry as oral history – ~2000 BCE

Epic poetry used techniques of metrics and rhythm to commit long stories and myths to memory. Bards passed these to many people as they travelled through song. The most famous examples are the Epic of Gilgamesh and The Mahabharata which survived long enough to be written down.

Modern printed version of the Mahabharata epic

The socratic method – 500 BCE

Socrates' classical inquiry method of engaging in cooperative dialogue and responding to everything with a question. Enabled critical thinking and scepticism of every possible assumption and presupposition in an argument.

Monsiaux's painting; 'The Debate of Socrates and Aspasia'

The scientific method – 1000~1400 BCE

Another classic. Hypothesis, empirical observation, experiments, and shared cumulative facts fundamentally changed our ability to understand the physical world around us. Allowed us to harness that information in the service of disciplines like engineering and medicine.

Vermeer's 'The Astronomer'

Vermeer's 'The Astronomer'Cartesian coordinates – 1637

Rene Descartes' system of assigning numbers to points on an X - Y - Z axis. Allows us to model and map areas of 3D space using precise measurements. Enabled us to draw up plans for objects and structures that don't yet exist. Also enabled mapping latitude and longitude points on earth, and eventually GPS

The X, Y, Z axes of the cartesian mapping system

Zettelkastens – 1500s

An information management system based around linked index cards. Each card holds a single belief or succinct statement, a unique number or code, and links to its source references and any related cards. The system allows researchers to collect and organise large amounts of information, and create many flexible 'chains' of cards to synthesise into original arguments.

A single index card from Niklas Luhmann's Zettelkasten

Aboriginal songlines – ~60,000 years ago

Songlines are physical paths through the Australian landscape that Aboriginal people have used for tens of thousands of years as mnemonic devices. They have songs they sing that correlate to specific paths and encode information about the land, political and social rules, and cultural knowledge. Similar to

, but shown to be more effective in memorising vast quantities of information.

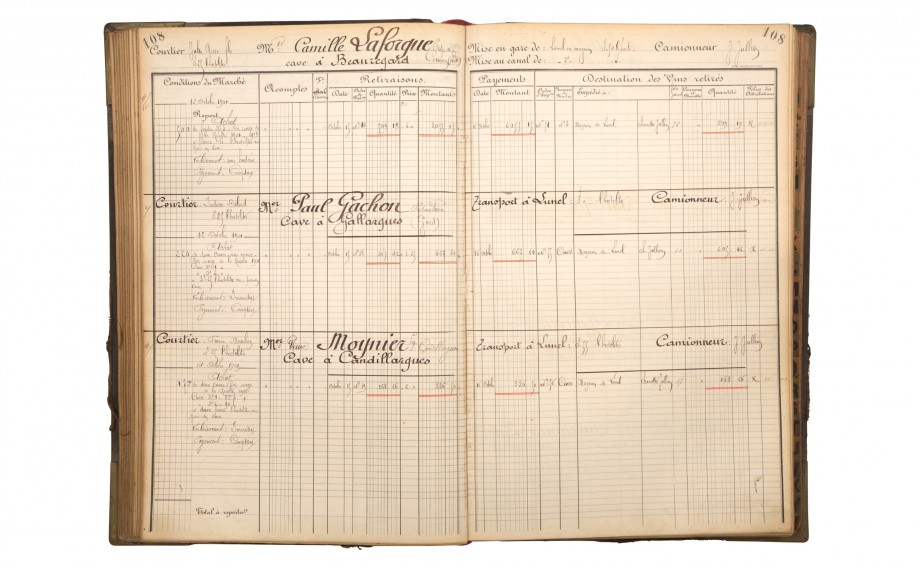

- Spreadsheets

Paper spreadsheets (also called ledgers) were used for accounting; the column and row format allowed bookkeepers to track and calculate large volumes of income, costs, taxes, etc. The power of spreadsheets undeniably exploded when they made the jump to digital mediums, but the base format has been around for hundreds of years.

Data visualisation – 1785

Visuals that map quantitative data onto shapes, lines, colour, and spatial relationships. Allows us to visually compare, contrast, and see patterns in a large amount of data.

The first data viz; William Playfair's map of the Bank of England's balance over time

Each of these examples profoundly transformed the kinds of thoughts humans can think. They expanded our cognitive abilities and allowed us to solve problems that would otherwise be unsolvable.

It might feel strange to call some of these things “tools”. The scientific and Socratic methods seem more like techniques for problem-solving. While drawing and writing are surely mediums or representations of ideas rather than “tools”?

Part of this discomfort is a limitation of language. “Tool” is a tricky category that we most often associate with physical objects. But we also use it to refer to less tangible techniques and mediums: fire, software development kits, slam poetry, democratic voting systems, design thinking, metaphors, and Google search filters are also called “tools.”

I do think there's a meaningful distinction between tools and mediums: Mediums are a means of communicating a thought or expressing an idea. Tools are a means of working in a medium. Tools enable specific tasks and workflows within a medium. Cameras are a tool that let people express ideas through photography. Blogs are a tool that lets people express ideas through written language. JavaScript is a tool that let people express ideas through programming. Tools and mediums require each other. This makes lines between them fuzzy. And I'm unconvinced there's much utility in sharpening them.

I'm going to proceed with a generous definition of “tool” for the rest of this piece. We could spend time splitting hairs and trying to hash out these categories. Or we could plough on by accepting any object, cultural practice, technique, or medium that expands human abilities as a tool.

This gives us a mental model that looks something like this:

Most of the examples I listed above are cultural practices and techniques. They are primary ways of doing; specific ways of thinking and acting that result in greater cognitive abilities. Ones that people pass down from generation to generation through culture.

Every one of these also pre-dates digital computers by at least a few hundred years, if not thousands or tens of thousands. Given that framing, it's time to return to the question of how computation, software objects, and note-taking apps fit into this narrative.

The Computational Roots of Tools for Thought

My simple interpretation of “tools for thought” up to this point takes the phrase at face value – devoid of any historical context. Any sincere and holistic exploration of the phrase has to consider who came up with the term, and what particular cultural and historical contexts they were part of.

If you look around at the commonly cited “major thinkers” in this space, you get a list of computer programmers: Kenneth Iverson, J.C.R. Licklider, Vannevar Bush, Alan Kay, Bob Taylor, Douglas Englebart, Seymour Papert, Bret Victor, and Howard Rheingold, among others.

I would be remiss not to point out all of these figures are male, white, from North America, and associated with various prestigious technical universities such as MIT, Caltech, Stanford, and UC Berkley. Most were hanging out in California from the 1960s up through the 1990s working on advances in networked computing, personal computing, and interface design. This demographic is so overwhelmingly consistent that they're sometimes called the “patriarchs” of tools for thought.

This is relevant because it means these men share a lot of the same beliefs, values, and context. They know the same sorts of people, learned the same historical stories in school and were taught to see the world in particular kinds of ways. Most of them worked together, or are at most 1 personal connection away from the next. Tools for thought is a community scene as much as it's a concept.

This gives tools for thought a distinctly computer-oriented, male, American, middle-class flavour. The term has always been used in relation to a dream that is deeply intertwined with digital machines, white-collar knowledge work, and bold American optimism.

A History of Computational TFT

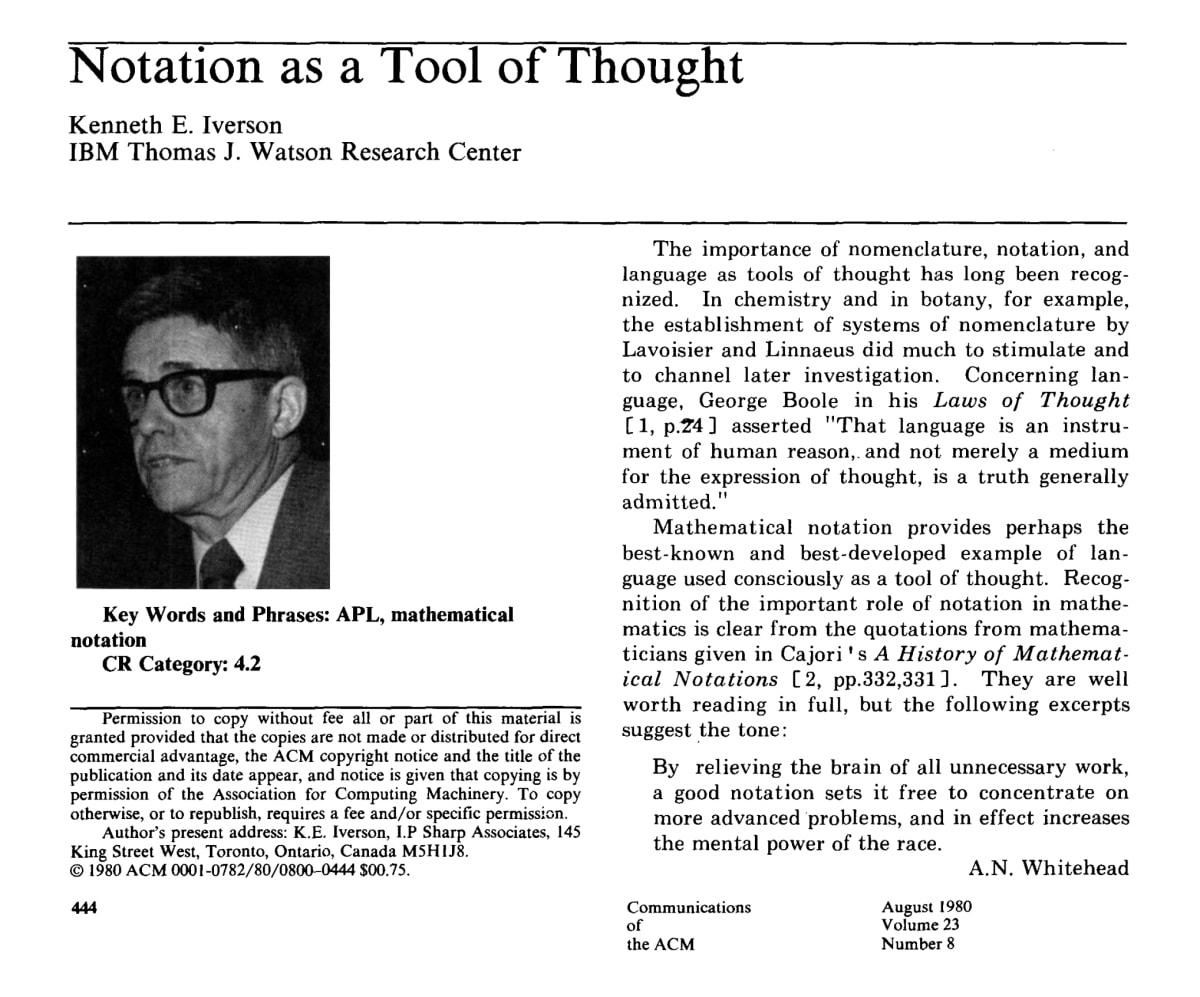

The phrase itself is not that old. It was first used by Kenneth Iverson in his research work on programming notation throughout the 1950s and '60s.. His first public paper mentioning it is

published by the ACM in 1979.

Iverson's 1979 paper on mathematical notation as a tool for thought

Iverson argued that establishing shared notation within a discipline – be it biological, mathematical, or programmatic – can relieve our working memory and compress complex meanings into concise forms.

Notation is only one small aspect of the larger tools for thought vision. While Iverson was the first to give this philosophy a distinct name, others were already exploring many of the same themes using different terms.

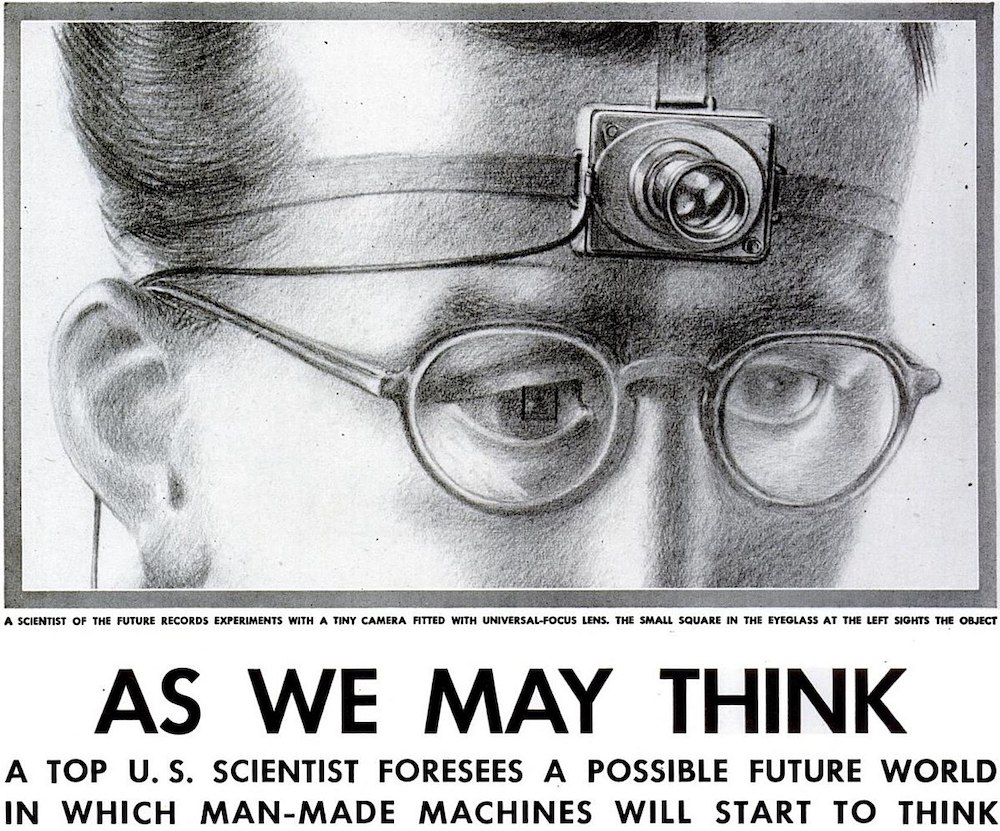

Back in 1945

published an essay titled

in both The Atlantic and Life Magazine – two publications with a wide readership. In it, he proposed the

, an imaginary “memory extension” machine that would help people explore information and craft their own hyperlinked research journeys through it. Many of the later thinkers in the tools for thought movement cite this article as a key influence.

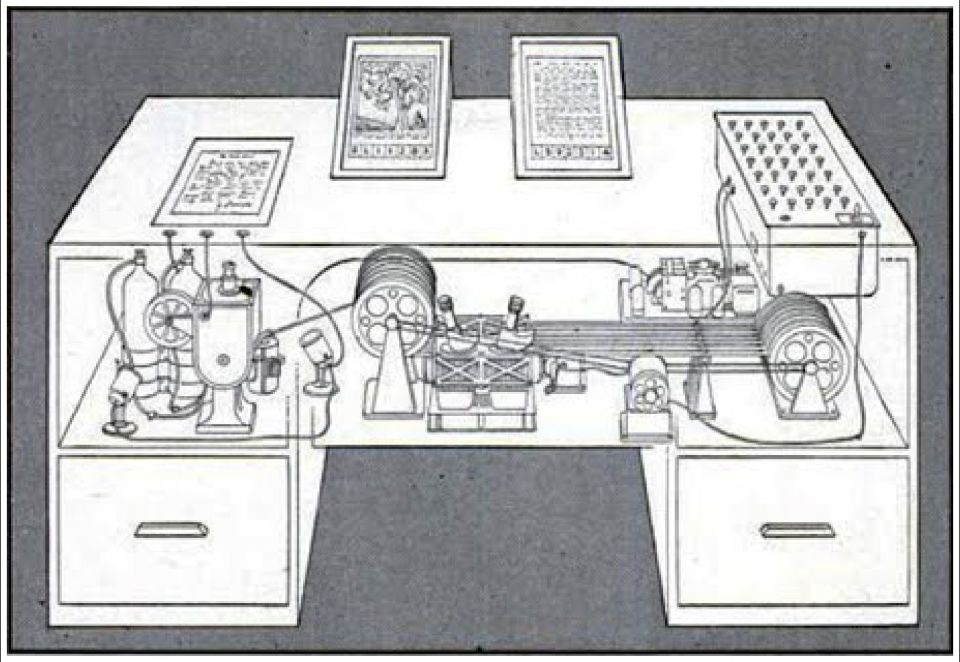

Vannevar's vision of a Memex machine – a desk with built-in microfilm displays

This is one of the earliest visions of how computers might be able to augment human cognitive capacities. Others soon took up the mantle.

built on Vannevar's ideas throughout the 1950s and '60s while teaching at MIT. His 1960 article

predicts a future where "men and computers cooperate in making decisions and controlling complex situations." Where we would have marvels like “computer-posted wall displays” for critical data, and “automatic human speech production and recognition.”

That all sound quite banal to us now. We have plenty of giant dashboards and voice assistants. Every decision made in complex situations like government, infrastructure engineering, medicine, or law involves extensive (hu)man-computer collaboration and augmentation. We have already achieved many of the wildest dreams of this generation. Computers are deeply integrated into every institution. And every individual life. They are affordable, easily accessible, and always available. Literally in our pockets.

But simply because we've drastically improved human-computer collaboration since 1960 doesn't mean we've peaked. It's still unclear how much our current status quo helps or hinders our capacity to deal with complex problems. The work of

helps shed some light on this. His extensive essay

(1962) has become a touchstone for the community. It proposes a more ambitious vision for using computers to extend our cognitive abilities.

Draft in Progress

The quality of writing below this point is haphazard, disjointed, and nonsensical. It's probably a good idea to come back later.

After Bush, Licklider, and Englebart's well-publicised presentations and writing made the rounds, many other thinkers became interested in the problem of expanding human reasoning with machines. Much of the relevant innovation happened at

where thinkers like and built the foundations of modern personal computing.Kay's team chose to talk about it in terms of giving people “personal dynamic media” to think with.

In his 1989 essay , Kay...Much of this history is outlined in Howard Rheingold's 1985 book

– an account of major innovations that led to the personal computer and the philosophical lineage of those building it. Michael Hiltzik's also recounts a lot of the work done at Xerox PARC.

Tools for Thought

Howard RheingoldRheingold tells the story of what he calls the patriarchs, pioneers, and infonauts of the computer, focusing in particular on such pioneers as J. C. R. Licklider, Doug Engelbart, Bob Taylor, and Alan Kay

Dealers of Lightning

Michael HiltzikA historical tale of Xerox PARC throughout the 1970s and '80s. Traces the development of the first personal computer, the laser printer, and the graphical interface. Based on interviews with the scientists, engineers, administrators, and executives who were part of the lab.

I'll refrain from recounting the entire history here. My point is that all of these thinkers exclusively focus on computers as essential to enabling new ways of thinking. They aren't exploring how meditation, architecture, complementary medicine, or music composition might enable new kinds of thoughts. The computer is essential.

Beyond Computers: Cognitive Scientists, Philosophers, and Tools for Thought

Plenty of people have used the phrase and explored many of the same topics outside of the context of computer science. There is a rich lineage of cognitive science researchers and philosophers who ask “how can we develop better tools for thinking?” without presuming computers are a critical part of the answer.

, a biologist and philosopher, published a book by the same name as Rheingold eight years earlier in 1977. In it, he explores the nature of complex systems and discusses philosophies and problem-solving tools for wicked problems. Computers are mentioned in passing but are never the focus.

Tools for Thought

C. H. WaddingtonWaddington presents a set of philosophies and problem-solving tools for dealing with complex systems. The book covers classical systems thinking topics like hierarchical dynamics, feedback loops, zero-sum games, and forecasting.

The philosopher Daniel Dennett published Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking in 2013

Tim Ingold is both an anthropologist and philosopher who has written numerous books about our relationship to and perception of our physical environment.

We'll return to these non-computational interpretations of “tools for thought” later on. They shouldn't be dismissed or cast as irrelevant to the narratives that computer nerds have written.

Computers as the Meta-medium

Is this particular focus on computers justified?

Alan Turing first called computers “universal reasoning machines” – machines capable of simulating many other kind of machines. General purpose machines expand what is possible. Computers as a meta-medium that can mimic all other kinds of mediums. They mimic paper and pencil, calculators, painting canvases...

Computers can dynamically simulate

"Computers are without a doubt the most potent thinking tools we have, not just because they take the drudgery out of many intellectual tasks, but also because many of the concepts computer scientists have invented are excellent thinking tools in their own right." - Dennett (2013)

It would be more accurate to rename tools for thought to computational mediums for thought. Or CMFT for short.

CMFT would actually be a subset of the larger field of tools for thought, since as we established earlier, the vast majority of historical tools for thought are not in the least bit computational.

[image of CMFT as a subset of TFT]

Which should make us pause to ask: Are CMFT's significantly different to other TFTs?

The Second Wave of Tools for Thought

A major narrative within the tools for thought community is the loss of historical progress. There's a lot of lamenting the historical break between the early pioneers of personal computing and the current state of computing. The nineties and early oughts are cast as the fallow times. While software “

,” millions came online, and Windows 95 graced every desktop, this period is seen as a turn away from the original vision.Bret Victor was the first to call attention to this historical gap in a series of talks between 2013 to 2015.

and 's 2019 essay on helped kick off the new popularity wave, as well as Andy's and writing advocating for TFT as a field.

Matuschak and Neilson's essay made a dent in the software development community.

Rise of the Note-takers

Around the end of 2019, as Matuschak and Neilson's essay is being passed around, we begin to see the rise of a few new "note-taking" apps. I put "note-taking" in quotations because the activity we're going to talk about here is only tangentially about taking notes, but we've all taken to using the idea of note-taking as a shorthand way to refer to it.

What we are talking about is software that allows people to enagage in a few key activities:

- Write in a linear text format

- Collect information

- Store information

- Search and find information

- Connect information

Before this moment, the major players in the market are tools like Evernote, OneNote, Notion, and Apple Notes. There are plenty of smaller apps serving niche use cases. But there's a clear inflection point in mid-2020 in this field where the number and diversity of “note-taking” applications drastically increases. [need evidence for this claim]

is one of the central software characters in this story. In late 2019 and early 2020 the beta version gains a slew of new usersObsidian comes out in xxxx. Logseq is released in xxxx. At this point it seems the floodgates are open.

In short order, we get Clover, Craft, Remnote, Mem.ai, Scrintal, Heptabase, Reflect, Muse, Thunknotes, Kosmik, Fermat, and XXX.

There's a scramble to make sense of all these new releases and the differences between them. YouTube and Medium explode with DIY guides, walkthrough tours, and comparison videos. The productivity and knowledge management influencer is born.

[ giant wall of productivity youtube nonsense ]

The strange thing is, many of these guides are only superficially about the application they're presented in. Most are teaching specific cultural techniques:

Zettelkasten, spaced repetition, critical thinking.

These techniques are only focused on a narrow band of human activity. Specifically, activity that white-collar knowledge workers engage in.

I previously suggested we should rename TFT to CMFT (computational mediums for thought), but that doesn't go far enough. If we're being honest about our current interpretation of TFT's, we should actually rename it to CMFWCKW – computational mediums for white-collar knowledge work.

Thinking Beyond Digital Note-taking

By now it should be clear that this question of developing better tools for thought can and should cover a much wider scope than developing novel note-taking tools.

- Forecasting and prediction markets

- Guesstimate

- Squiggle

- Better critical reasoning

- Socratic debate

- Audio and visual

- Photoshop

- MaxMSP

- Logic Pro

- Jacob Collier streams

- Game dev and dynamics

- Houdini

- Blueprint

- ML Assistants

- Elicit for rigorous research

- Spatial understanding

- Nothing that teaches the Alexander technique, movement, spatial awareness, dance

Recorded talk version

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK