A Hard Inheritance

source link: https://sarahstankorb.medium.com/a-hard-inheritance-2f24adb79247

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

A Hard Inheritance

Unpacking the baggage from my family home

“One day, all this will be yours.”

It was a promise my mother made years ago, wanting to assure me that I’d have some sort of inheritance. I scoffed. All I’d ever wanted was to escape my childhood home.

I also knew better. I knew how little they had saved. Whatever value resided in the walls of their century-old home was all they’d have in old age.

I’d inherit the obligation to clear out their decades’ of stashed garage sale goodies, the cobwebs, the memories.

Over a recent weekend, my husband and I wrapped what I hope will be the final stage in preparing a house I’ve always hated for sale. My parents have grown increasingly ill and weak over recent months and are now in a nursing facility near my home, all of us across the state from where I grew up, hours from that old house.

On prior trips, we salvaged the clothes and old family photos, not realizing even older photos — including one of my great-, great-grandfather from 1891 — were stored in boxes at the back of a closet. We’d been bleary-eyed, not believing that this stage had actually come. My forceful and at times terrifying father can now only creep a few feet across the room. His constant, anxious phone calls have become the background music of my life.

This time, we were more strategic with the house. All the furniture we’d moved in recent years to get my parents safely positioned on the ground level returned to its native location, a redistribution we hoped would better stage the home and help a buyer see themselves there.

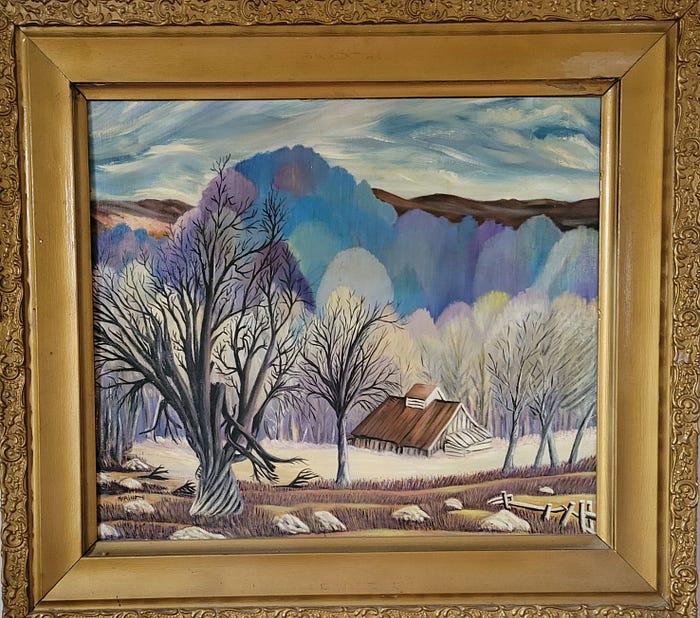

My eyes caught on one of the eerie portrait prints hanging around the house with oily shadows of black and brown. There’s the lonely girl in a barn hanging in my old bedroom; the woman sitting alone in shadows doing needlepoint; the woman sitting alone reading; the barren landscapes with grey, leafless trees; the despairing farm family in a fallow field; the impression of a sorrowful girl painted in reds and browns; the red-headed child with tears brimming her eyes.

As my brother carefully removed china from a full cabinet, this theme finally struck me, and I called, “Did you ever notice how dark all the art is here?”

He shrugged and laughed a little, more focused on the task at hand.

It’s funny how many years you can pass through a setting without seeing it in full, without observing how the mood of the family within had come to fuse with the surround.

I sat in the front hallway, dumping out the downstairs desk.

Here were phone books from the 1980s, letters to my father demanding child support he refused to pay for children from previous marriages. In contrast, there were the dog’s adoption papers and shot records, carefully filed in a special drawer. Throughout was the haphazard mingle of old greeting cards and W-2s.

I found an old photo: my dad, my brother and I at the bar where my father spent his days. The dank place doubled as childcare for me over summers while my mother worked. (I was not supposed to tell her.) My brother wore hammer pants, and he and my father held pool cues. My body was turned begrudgingly toward the camera. I smiled weakly but kept my hands on the pinball machine flipper buttons — I was careful not to lose my chance to play.

In the desk there was a note from the church from when it covered our electric bill one month. (It was the church my mother cleaned on Saturdays to supplement her income.) As I dug deeper into the drawers, I found further documentation of my childhood poverty and the choices my father made that kept us there no matter how hard my mother worked.

The desk was just a l’aperitif for what lay ahead.

Upstairs in my mother’s office, there were dressers and filing cabinets overflowing with more — drawers and drawers of papers transported over but never discarded years ago when my grandmother reached this perilous stage of life. Some files held paid bills, tucked back into their envelopes, dating back to the 1990s. I found manuals for my mother’s adaptive computer software, the advantage that made it possible for her to keep working as a transcriptionist despite tremors from the neurological disorder, dystonia, that impacted her entire life.

I saw recognition of her disability, her drawers of tapes and letterhead and medical dictionaries, a personal industry developed in an effort to labor past handicap to keep her family housed and fed. Just half an hour prior, I’d taken cathartic pleasure in ripping through my father’s old lotto books, also retrieved from the family desk. Upstairs, at my mother’s own desk, was evidence of so much work to bring money home. Downstairs I’d found just one of the ways it spilled back out.

My mother wasn’t diagnosed with the movement disorder dystonia until I was in my twenties, and she in her sixties, when I talked her into trusting one last doctor. After years of no answer, just quizzical looks from strangers upon hearing her voice and tolerating aching hips and arms from her body’s efforts to contort against her will, she’d given up on a diagnosis. She just tried to operate around it.

I remember how she’d let me play under the church pews while she cleaned on Saturdays — paid $50 per week or per month, I can’t recall. Now that I’m an adult with inherited dystonia, I know too well how her body must have ached as she bent and scrubbed.

“I have another can full up here,” I called down to my husband who was driving trash cans of paper downtown to the recycling center as I stuffed them. He’s there, always, lifting what I can’t, sliding into rooms as I see more evidence of the unfairness of my mother’s life.

I broke down crying.

In yet another drawer, I found a fat file, unlike the tidy others in my mother’s main filing cabinet. A maternity ward ID was clipped to the edge — and I smiled. It was from my mother’s visit when our son was born.

Inside the file was what looked like every byline I’d had in my young life. My poem in the newspaper Mini Page from fourth grade, my teenage letters to Youngstown’s Vindicator editor (I often had complaints ready to share), high school papers, my first essays published as a freelance writer. I had no idea she’d saved any of it.

When we’d packed Mom up months before for respite care at the local nursing home, we asked if she wanted to say goodbye to the home where she’d lived for over thirty years. She just shrugged and cruised out with her walker. I never knew her as sentimental.

But in other drawers, I found cards I’d written to her, a glass framed verse: “Mothers make little miracles sprout, and watch them while they grow. And when they’re grown and looking out, with love, she lets them go.”

I was in her office discarding can after can of a life’s detritus. Back, just briefly. It was the room where she labored for so many years, while she raised me. A notion struck me, that I had been the great work of my mother’s life, her pride tucked into corners in a house she was ever trying to earn enough to keep — and one I was so eager to flee.

A neighbor stopped by and sat in the office for a bit while my brother and I emptied more drawers. He observed how the feel of the place was starting to change. My husband was removing curtains, letting light in. I’d never noticed just how dark the house was. I guess after so many years, I learned to take for granted how my eyes would have to adjust as I walked out into the stark brightness outside the interior gloom.

“I have to ask, what’s up with the art here?” the neighbor queried, gazing at a painting that either depicts a man napping after reading a book or having died from boredom. (I’ve always assumed the latter.)

“I just noticed that!” I said in wonder. Although, it wasn’t actually that astonishing that we’d both been struck by this observation — with the clutter removed, the art’s ennui stood out.

With sunlight streaming in, the home’s habitual darkness only showed contrast. With my parents moved out, only now did I really start to see the contours of their lives.

Over Sunday dinner after another round of sorting, I fumed over how much of their meager funds my father had wasted over the years on drinking and gambling (and smoking and garage sales and, and, and…). My husband centered himself, looked me in the eye, and said with remarkable grace, “Your father’s depression destroyed his life, and it could have destroyed all the lives around him.” He was working to reach my empathy.

Happy people don’t live as my father did. I know that.

It’s hard to see, with a child’s eyes, beyond the rage of an alcoholic to the depression that he’d medicated.

My mental map of the family house is one that traces the lines where he’d chase me, screaming, up the stairs. I’d dart behind my bedroom door, where I listened to him pound. If he was distracted enough in his anger at me, that meant my mother was safe. Once he’d pass out, I’d stay on the inside of my locked door, staring up at the white tile ceiling at little stains I pretended were faces. I imagined stories for them, aliens from distant worlds, gods, goddesses. My imagination could open other doors for me, one day, get me out of that house.

And now in what may have been my last visit, I had to clear almost all of it away. I don’t know how to get an almost hundred-year-old house clean, really. I don’t know how to cleanse myself of the echoes of that place. Its shadows and fear cast way out into my adult life. My body is trained not to feel safe around raised voices. I still hate the smell of whiskey.

But my father is sober and so small now. I outweigh him and without me, he’d be without an advocate, trying finally, to get him help for moods that swell and still overtake him. My mother slips in and out of knowing. Memories slosh between now and a distant more cheerful past, before she was married, or snippets of when I was young, her little child full of potential and ambition she saw as enough for both of us.

When I left, finally, my car was filled with her favorite old country rose china, a recliner for her nursing home room, and boxes of old pictures from when she was young and fierce and beautiful. I ran errands to their bank, to a hospital supply place to drop off my dad’s equipment, to the courthouse to file papers on their behalf. As I wound through town, I passed the streets where childhood friends grew up, then our first neighborhood, and the house we lost when my father lost his job when I was six.

In truth, the old home I’d just packed up saved us then.

We’d been about to become homeless when my dad heard about a house trashed by the last renters. What would become my bedroom door had a drawn-on bullseye and bullet holes he’d have to fill. We could live in it, though, have a home under a roof, if my dad patched it back up. Eventually, the rental would turn into rent-to-own, and in between, my father accomplished years of maintenance. His labor in keeping that house has been one patch and project at a time. He loved the house, even when he didn’t know how to show that kind of love to the people in it.

With the curtains off the windows now, the house reminds me of that first visit. We could just peek in from the front, and my mom spotted the strange wallpaper on the walls of the room she’d insist on calling “the library.” Floor to ceiling and skirting the built-in bookshelves was wallpaper sporting a reproduction of old ads from the late 1800s. It featured women in bustles trying a hair treatment “for the badd & the grey,” a man in breeches riding a penny-farthing. It was a testament to farm ads, the glory of a good seamstress, and industry, all in deep greens, orange and brown. It was old-fashioned and strange.

But my mother’s eyes lit up that first time, seeing something she found beautiful inside. She could just picture it then, the life we might still have.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK