The mechanics of non-human personas

source link: https://uxdesign.cc/the-mechanics-of-non-human-personas-d5222b0c0753

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

The mechanics of non-human personas

How designers can capture the voices that represent non-human living beings.

This is the second part of a series of articles based on a recently published academic paper Non-Human Personas: Including Nature in the Participatory Design of Smart Cities, which I co-wrote with Joel Fredericks, Dan Vo and Jessica Frawley from the Sydney Design Lab and Marcus Foth from the More-than-Human Futures group.

In 1969, the United States Forest Services accepted a proposal from the Walt Disney Company to turn the Mineral King subalpine glacial valley into a ski resort. The development received strong criticism because of its commercial motivation and the devastating damage it would have brought upon the valley and its wildlife. To speak up on behalf of the environment, the Sierra Club stepped in and attempted to block the development arguing that it would cause irreparable harm to the public interest.

After years of court hearings, the project was ultimately deemed to be too costly and lost support from the U.S. government. But the case Sierra Club v. Morton received global attention as it led a justice to argue in his dissent that natural resources ought to have standing and the ability to sue in court [1].

Almost 50 years later, in March 2017, the Whanganui River in New Zealand was the first river to be granted personhood [2]. A landmark moment in law, the decision was made to help protect the environment and natural resources.

Having the status of a legal person enables the Whanganui River to sue in court. Two nominated guardians—a representative of the New Zealand Government and a representative of the local Māori tribe of Whanganui—defend the river’s rights and interests and promote and protect its health and wellbeing [2].

The Whanganui River in New Zealand is represented by two nominated guardians that speak on behalf of the river and its ecosystem / Photo by Tim Proffitt-White via Flickr

Considering non-human stakeholders in a design process

How to give natural resources a right to defend themselves has been a longstanding debate in law, gaining a global momentum with the publication of a book by Christopher D. Stone titled Should Trees Have Standing? [3]. Other nations have followed the New Zealand example and granted personhood to their rivers and ecosystems.

While cases like Sierra Club v. Morton feature in the modern curricula of law schools, design education usually doesn’t teach us how to represent nature as part of a design process.

Yes, there are important movements like sustainable design, eco design and circular design. And industrial designers would have likely had to study Victor Papanek’s influential 1972 book Design For The Real World, in which he famously wrote “There are professions more harmful than industrial design, but only a very few of them” [4].

Design For The Real World by Victor Papanek / Photo via Twitter

We can replace “industrial design” with “interaction design”, “UX design” or “service design” and the quote is still accurate. The impact of our digital interactions on the environment may be less visible compared to physical products but very real.

There are plenty of tools and frameworks to consider the environmental impact during a design process. But they, too, are mostly targeting the industrial design profession. They further largely treat natural systems as inanimate and passive.

Along with others [5, 6, 7], we have highlighted the ability of non-human personas to capture the concerns of all living beings and bringing their perspectives to the table when making design decisions.

Non-human personas are an extension of the original personas method [8, 9]. They allow designers to bring the perspectives of non-human beings into the design process and to consider them when making design decisions.

It is increasingly becoming clear that focusing solely on human needs and values has detrimental effects on the planet and humanity’s continued existence. Non-human personas address the limitations of human-centred methods by giving non-human stakeholders a voice in the design process [10].

Beans the possum

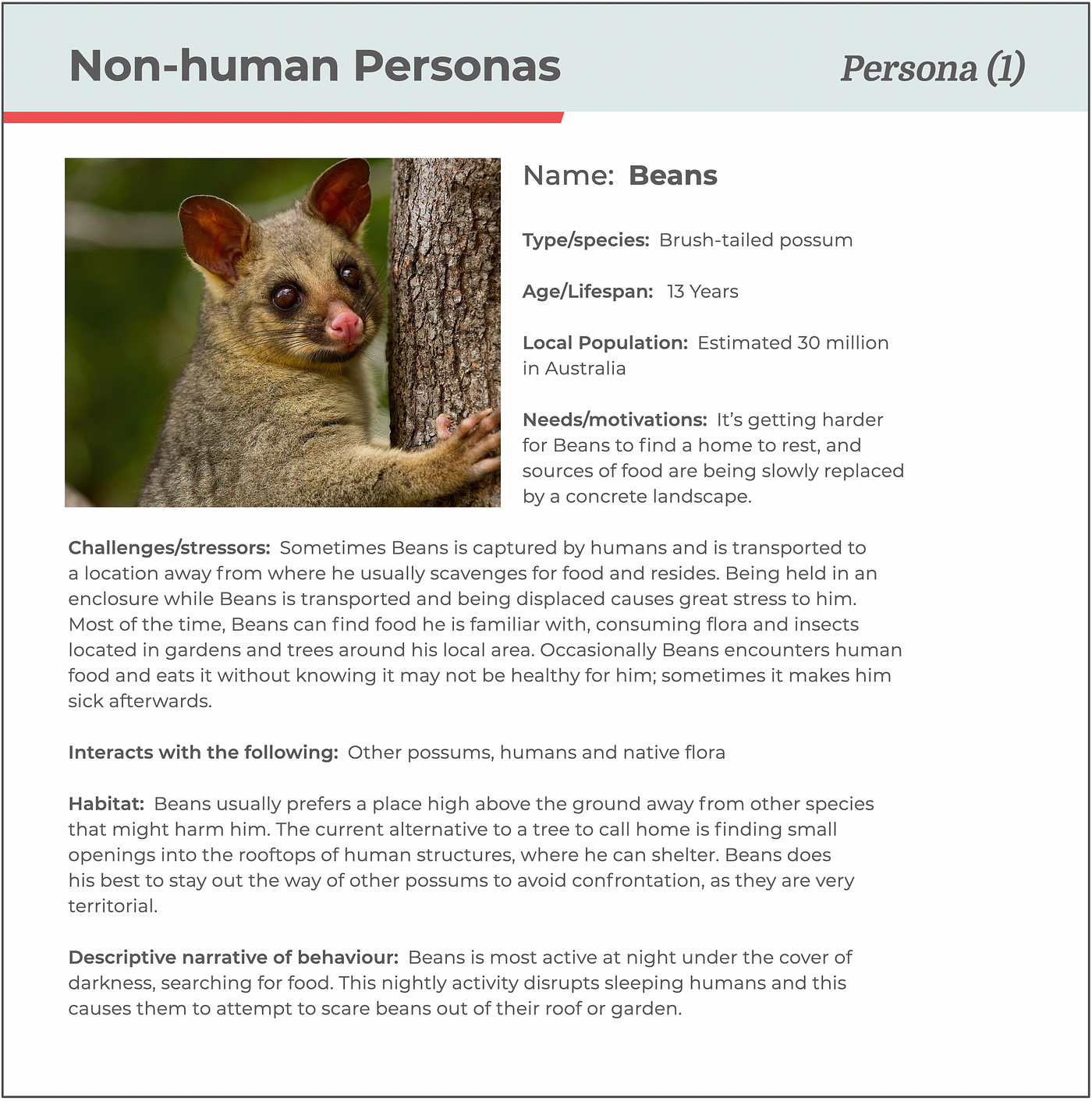

To better understand how non-human personas could be used in practice, we worked with Dan Vo—at the time a students in the Master of Interaction Design & Electronic Arts program—focusing on the design of a more-than-human parklet intervention. As non-human “users”, the study selected flora and fauna representatives that are native in the Sydney seaside suburb of Manly.

The emerging non-human personas were based on secondary data collated from relevant reports and followed a similar structure to the human personas — featuring needs/motivations, challenges/stressors, issues relating to habitat and food identified from the literature and a descriptive narrative of their behaviour. Details about ideal experience, goals, aspirations and feelings were excluded as it wasn’t possible to derive this information from secondary data.

The third-person form was adopted as this acts as a reminder “that the character remains grounded to a human perspective” [6].

The persona representation for Beans the possum based on secondary data collated from reports / Photo via Wikimedia

Throughout the design process, the personas then served as a representation to amplify the agency of the non-human stakeholders, who would not be able to make themselves heard in the participatory design process [11].

Going through the design process that prominently considered non-human stakeholders from the outset, allowed for addressing a new set of questions and gaining insights about the representation of non-human stakeholders.

The non-human personas proved successful at prompting and supporting expert participants with critiquing a design proposal through the lens of non-human stakeholders.

From the designer’s perspective, the non-human personas served as a reminder to keep the issues of non-human species in mind when making design decisions. To that end, they took on a similar function to human personas in interaction design projects, helping designers to “keep our users in mind every step of the way” [12].

It remained unclear, however, to what extent the non-human personas accurately encapsulated and represented the lifeworld of the respective species. Moreover, the project wasn’t able to capture their needs and desires in a holistic and reliable way.

Ideally, non-human personas — like traditional personas — should be based on primary data collected through field research [13]. However, this kind of primary data is more difficult to collect when it comes to non-human species.

As designers we could carry out contextual observations, but this can be difficult to achieve, for example, when dealing with nocturnal animals. Engaging in such observations further raises ethical questions, not covered through traditional ethics protocols, as the researcher might negatively interfere with the species and their ecosystem.

Capturing the voice of non-human stakeholders

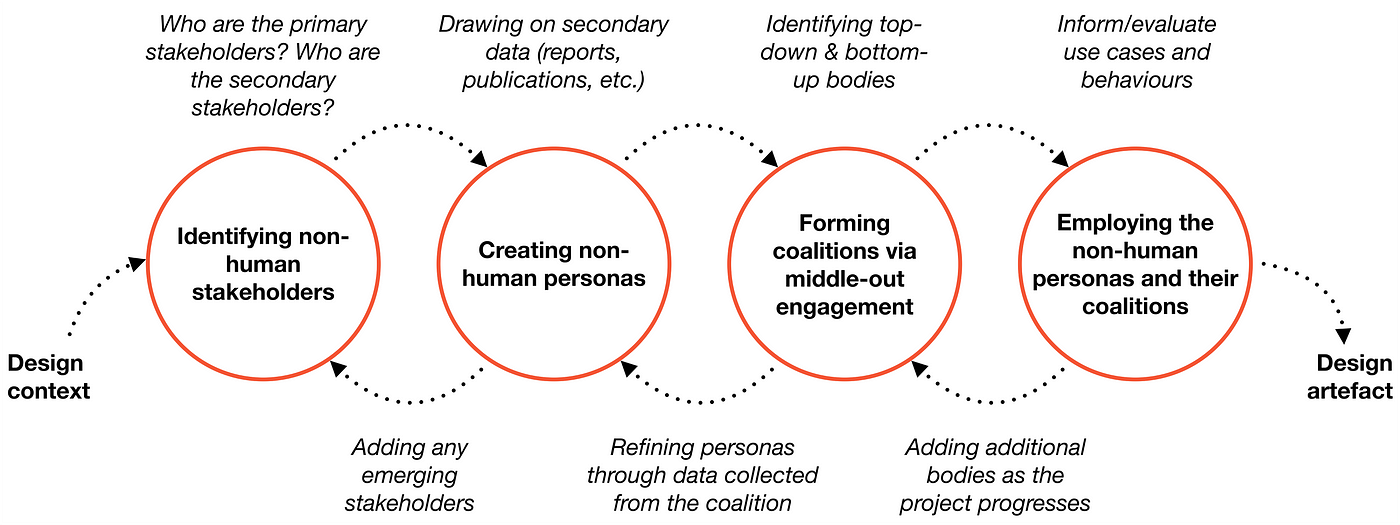

To address these challenges and to support the adoption of non-human personas in design projects, we propose a four-step framework.

Similar to how the Whanganui River is represented by two guardians, our framework involves the forming of a coalition that can speak on behalf of a non-human stakeholder in a knowledgeable and productive way.

The four steps of the non-human personas framework and the generative process for creating and improving the representation of non-human stakeholders / Source: [10]

The framework suggests the collection of primary data about non-human species through this coalition, which consists of representatives from the top and the bottom. This is akin to the two Whanganui River guardians being representatives from the New Zealand Government and the local Māori tribe of Whanganui.

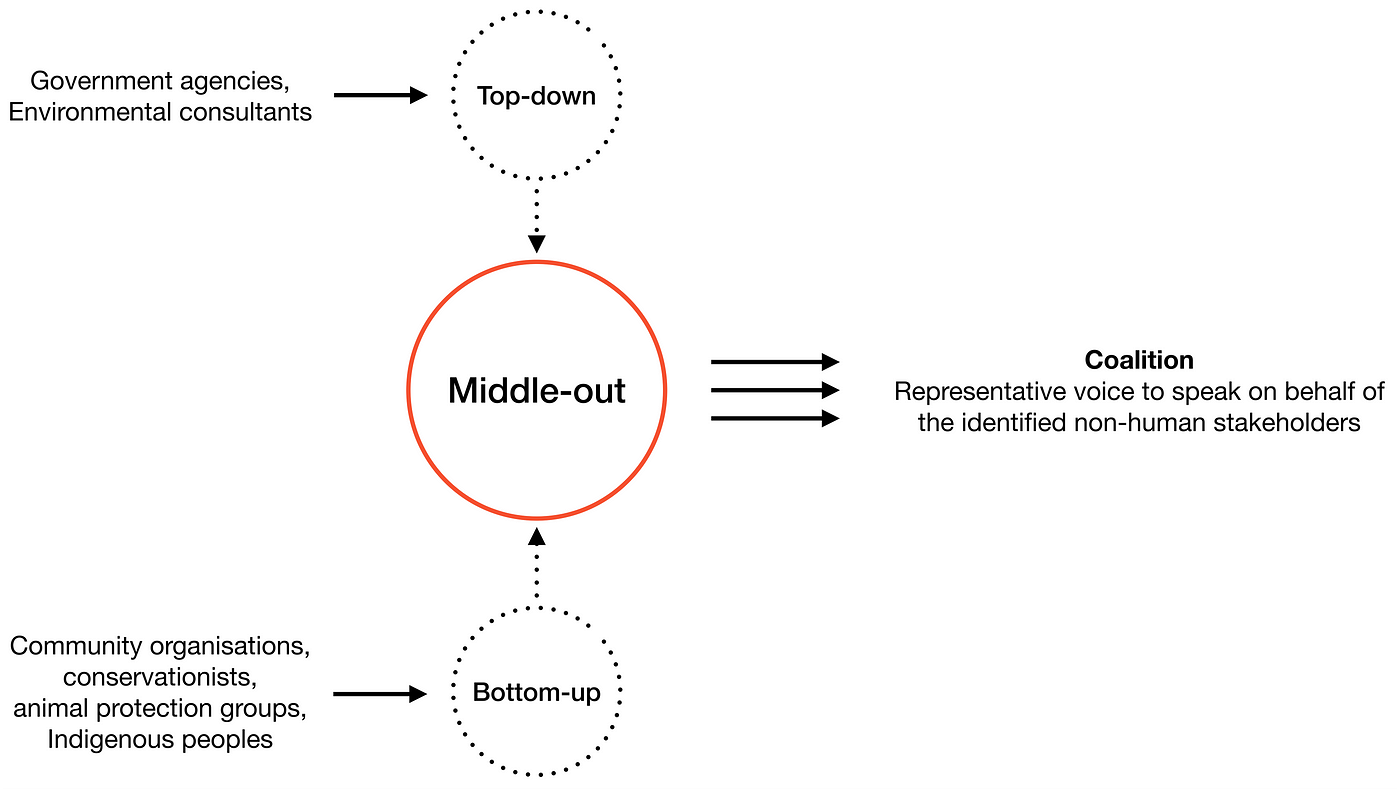

In the literature, this approach is referred to as a “middle-out” engagement [14, 15]. Middle-out engagement combines the collective knowledge of representatives from the top (government agencies, private enterprise) with those from the bottom (local communities, non-governmental organisations, Indigenous peoples).

The middle-out engagement approach for forming a coalition that is able to speak on behalf of an identified non-human stakeholder / Source: [10]

For example, top-down representatives could include people working in government agencies that drive policy and regulatory requirements for environmental and species protection, and ecologists that are undertaking investigative work for land management, agriculture and infrastructure development. Bottom-up representatives could include people that come from grassroots entities, such as conservationists, animal welfare groups, wildlife carers and Indigenous peoples, who have a strong connection to land and country.

Organisations in charge of top-down actions may not have the same level of knowledge about a local living system as, for example, local community groups. But their “buy-in” is critical for the efficacy and long-term success of an initiative since they control regulations, policies and other governance aspects.

Once formed, the coalition can be engaged through participatory methods, such as workshops and focus groups. A key outcome from these participatory sessions is the collective development of a descriptive narrative of the behaviour of the identified non-human persona. These narrative descriptions provide rich data that bring the persona to life [8, 16], ideally through a vivid story concerning the needs of the persona in the context of the design intervention [17].

Identifying non-human stakeholders

The framework’s first step—identifying who the non-human stakeholders are—can be challenging, especially in design projects where there are no obvious primary non-human stakeholders as “users” of the designed system.

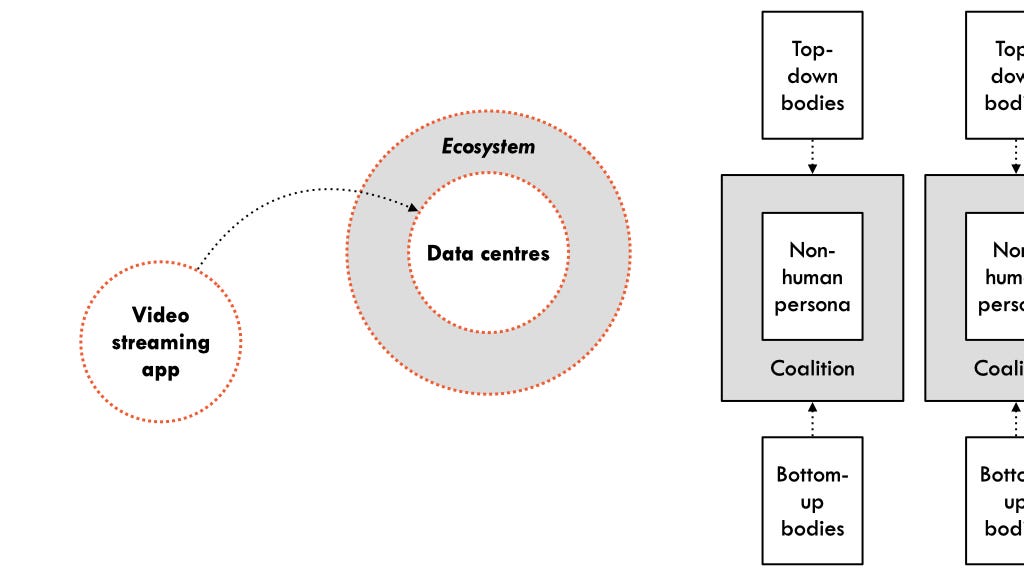

Designers may need to augment this step with other methods. For example, the impact ripple canvas can be used to identify a network of secondary and tertiary actions and to map out intended and unintended consequences of a design intervention [10]. Unintended consequences offer insights into a design intervention’s impact on the natural environment, such as the use of resources that may impact an ecosystem (e.g. space and electricity demands associated with server farms).

For example, if a designed solution involves streaming of video content (or the transfer of large files in some other way), designers need to ask critical questions about the data centres used to support these transactions. Depending on the location of the data centres and where the energy for its operation is coming from, there may be multiple living entities that are affected.

The use of video streaming has an indirect impact on ecosystems, which are home to multiple living entities that are affected by design decisions; each entity requires its own coalition / Source: author

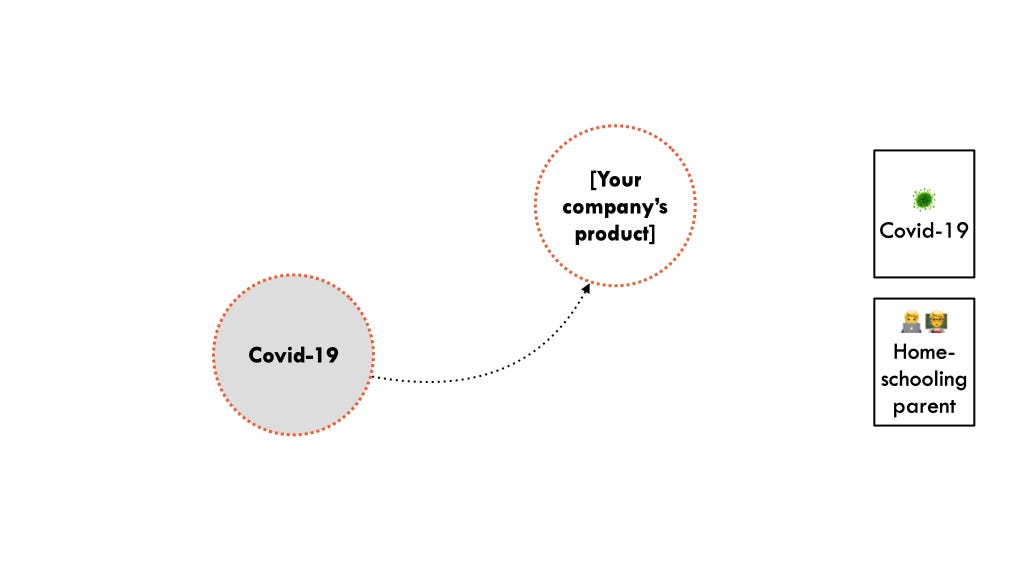

Some non-human stakeholders are closer and more obvious than one might think. For example, as Sznel points out, in 2020, Covid-19 was the “most important non-human stakeholder of every business and public service around the world”. In the case of Covid-19, the presence of the virus within communities may influence how design interventions are implemented, and even lead to new kinds of human personas, like the parent that is working full time while supporting their children with home learning.

The impact of Covid-19 can be captured through a non-human persona and also lead to new kinds of human personas / Source: author

Using non-human personas in practice

The same way that human personas serve as a way to keep the user centre stage [17], non-human personas act as a reminder to consider the direct and indirect impact of design decisions on the natural environment.

The coalition also remains a readily accessible resource throughout the timespan of a design project and beyond, carrying the voice of the identified non-human stakeholders.

Designers can use the coalition, for example, to test early prototypes of a design intervention, to provide advice on the launch of a product or to regularly assess potential unintended consequences once a design has been deployed.

In the next article, I will cover examples for projects that address non-human species as part of the design process and how this can lead to innovative design solutions.

Recommend

-

44

44

README.md GlobalWarming Minecraft Server Java Edition (Spigot) plugin which adds game changing climate change mechanics. Overview ...

-

70

70

README.md WaveFunctionCollapse This program generates bitmaps that are locally similar to the input bitmap.

-

34

34

The Cambridge University Press cover. This is the home page of the textbook "Modern Robotics: Mechanics, Planning, a...

-

59

59

README.md Paper

-

23

23

Hi HN, We’re JY & Julien, co-founders of Data Mechanics ( https://www.datamechanics.co ), a big data platform striving to offer the simplest way to run Apache Spark....

-

8

8

Introduction Since the beginning of my journey in computer security I have always been amazed and fascinated by true remote vulnerabilities. By true remotes, I mean bugs that are triggerable remotely without any use...

-

8

8

How do rockets really get to where they're headed? - Orbital MechanicsMy goal hereI am Alex, a huge space and aviation geek, working in the Aviation Industry for 11 years now. Ever since I was a child I...

-

7

7

Some core gameplay features make a return too Capcom's highly-anticipated The Great Ace Attorney Chronicles has just received a brand new trailer that showcases some of the new gameplay mechanics th...

-

8

8

Genesis of the Monte Carlo Algorithm for Statistical Mechanics This website stores data such as cookies to enable essential site functionality, as well as marketing, personalization, and analytics. By remaining on this website you indicate...

-

3

3

The case for using non-human personas in designWhy it is time to move beyond just designing for humans.

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK