Walter Tull: From Footballer to Soldier

source link: https://medium.com/lapsed-historian/walter-tull-from-footballer-to-soldier-310e21fb074e

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Walter Tull: From Footballer to Soldier

One hundred years ago today pioneering black footballer and British Army officer Walter Tull died. His story deserves more than a few passing paragraphs.

In recent years the story of Walter Tull has thankfully become much more widely known. In the telling, however, it has often become slightly muddied. You’ll sometimes find him labelled as “the first black footballer in England” or as “the first black officer in the British Army,” but he was definitely not the former and almost certainly not the latter either. Neither of these should diminish his achievement though. On both the fields of football and battle Walter Tull was a pioneer.

A West Indian Boy

In 1876 Daniel Tull, a former slave from Barbados, moved to Britain and settled in Folkestone. There he found work as a joiner and married a local girl, Alice Palmer. Together they had five children, including a son called Walter in 1888.

Walter’s childhood was not an easy one. In 1895, when he was just seven, his mother died. His father soon married Clara, Alice Palmer’s niece, but by 1897 Daniel too was dead, succumbing to heart disease. Unable to support all the children on her own, Clara was forced to place Walter and one of his brothers, Edward, in a Methodist-run orphanage in Bethnal Green.

It was in that orphanage that Walter’s talent with the football first began to emerge. He played on the left for the orphanage’s football team and, once he grew old enough to leave the orphanage, split his time between working as an apprentice printer and playing for Clapton in East London.

Taking the Amateur game by storm

Founded in 1877 as Downs Football Club, Clapton FC were one of the foremost amateur teams of their time. In 1890 they were the first British team to play competitively on the continent, defeating a Belgian XI 7–1 and in 1894 they became founding members of the Southern League. Indeed they still exist today, plying their trade in the Essex Senior League, although ownership issues mean the club is fighting for its existence. Go watch Clapton play today though and you will be watching them on the same pitch which Walter played, This is because Clapton still play at the Old Spotted Dog Ground in Forest Green, making it the oldest, continuously occupied, senior football ground in London (Clapton moved there in 1888).

Sadly, both the club’s existence and that relationship is now under threat due to ownership issues, meaning a new ‘community club’ may soon be required. Should this be the case it will mean a sad break in the history of one of Britain’s oldest clubs, but it may be the only way forward for its fans. This is a story for another time, but more information can be found here.

An amateur power house

When Walter joined Clapton though, they were a club at the peak of their power. True, the amateur game was on the wane and the team were finding it difficult to compete in increasingly professional confines of the Southern League, but they were still a force to be reckoned with.

Playing at inside-left, Tull began to make a name for himself. Described in local newspapers as the signing of the season he played a key role in their capture of the FA Amateur Cup in 1908/09, with one performance against Manchester United being described in the following, glowing terms:

Tull’s display on Saturday must have astounded everyone who saw it. Such perfect coolness, such judicious waiting for a fraction of a second in order to get a pass in. Not before a defender has worked to a false position, and such accuracy of strength in passing I have not seen for a long time.

It was at Clapton that Walter caught the eye of Tottenham Hotspur, and he was invited to join the club’s tour of Argentina and Uruguay in the summer of 1909. Despite finding the climate highly disagreeable, Tull made enough of an impression as a player to earn himself a transfer. On their return, the club announced that ‘Darkie’ Tull would be joining the club permanently, Clapton being paid £10 as a transfer fee and Walter earning the maximum permitted wage for a footballer at the time of £4 a week.

An unhappy time at Tottenham

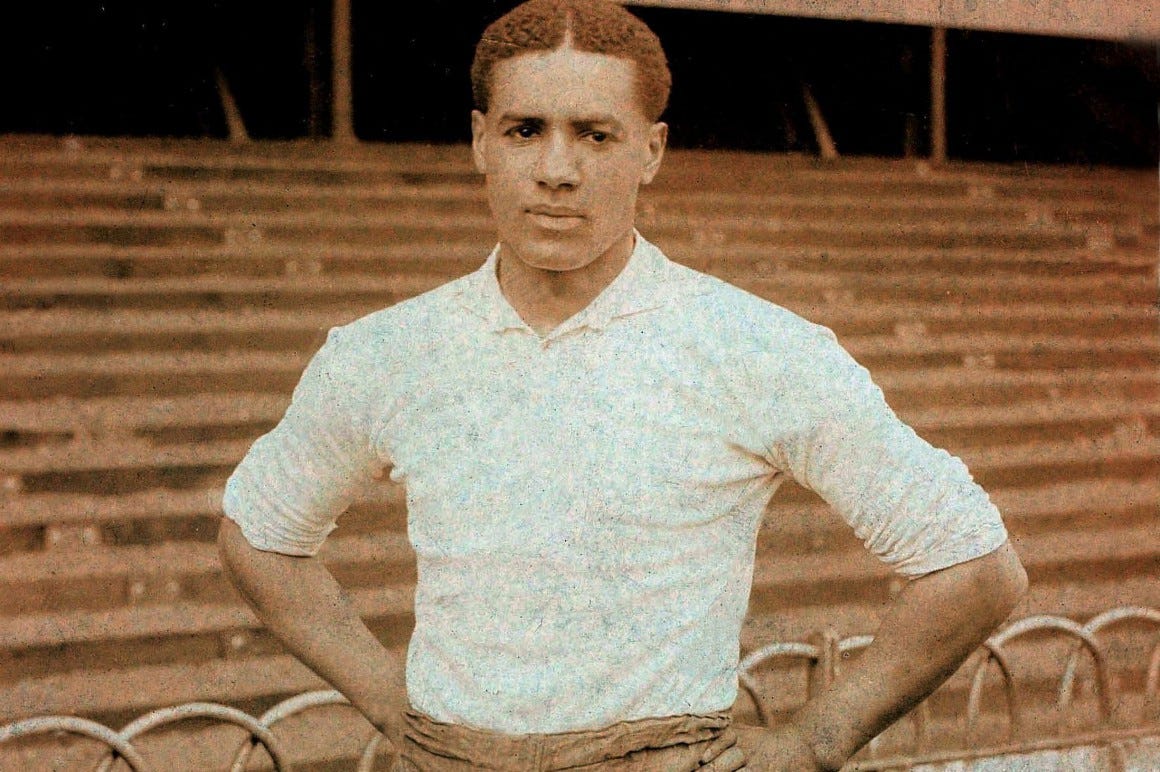

Tottenham Hotspur 1910/11 squad. Walter Tull bottom right. Source: Hellenic Spurs

Walter’s time at Tottenham was not an altogether happy one, although it began well enough. He started in six out of seven games at the beginning of the 1909/10 season, making his debut against Sunderland, but soon lost his first team place. Officially this was due to a perceived lack of pace, but the abuse that Tull received from the stands almost certainly dented his confidence and this continued to affect his performances. Against Bristol City in October, for example, the London press reported with distaste that a section of the crowd taunted Tull with “language lower than Billingsgate.”

By 1911 Tull’s football career had stalled. Since signing for Tottenham in 1909 he had made only twelve appearances in the league and FA Cup, becoming very much a bit-part player at the club. He was now largely to be found languishing in the reserves. Salvation was on the horizon, however — in the form of Northampton Town manager Herbert Chapman.

One of Football’s Founding Fathers

Herbert Chapman remains one of the few individuals who can legitimately claim to have invented the modern game. At Northampton Town, Huddersfield Town and then finally at Arsenal, Chapman pioneered many of the things football fans now take for granted: team meetings and the manager’s right to pick his team, positional play and tactics, and physiotherapy were all things he brought into the playing side of the game. At Arsenal he also introduced floodlights, shirt numbers, clocks in grounds and much, much more before dying, tragically, from pneumonia in 1934 aged only 55.

Indeed it is almost impossible to overstate Chapman’s influence on the modern game. His collected newspaper columns on football are still worth reading today, and are shockingly modern in thinking.

Herbert Chapman, during his time at Arsenal

In 1911 much of this was still to come. At Northampton though Chapman was already demonstrating his determination to look to the future, not the past, when it came to improving his team and the game. It was this that caused his eye to fall on the struggling Walter Tull and see an opportunity for both Tull and Northampton Town to benefit.

As far as Chapman was concerned, Tull’s colour was a non-issue. In part this was likely due to his generally forward-thinking nature, but Chapman was also one of the few former players and managers in Britain with first hand experience of working alongside a non-white footballer at a serious level — Arthur Wharton.

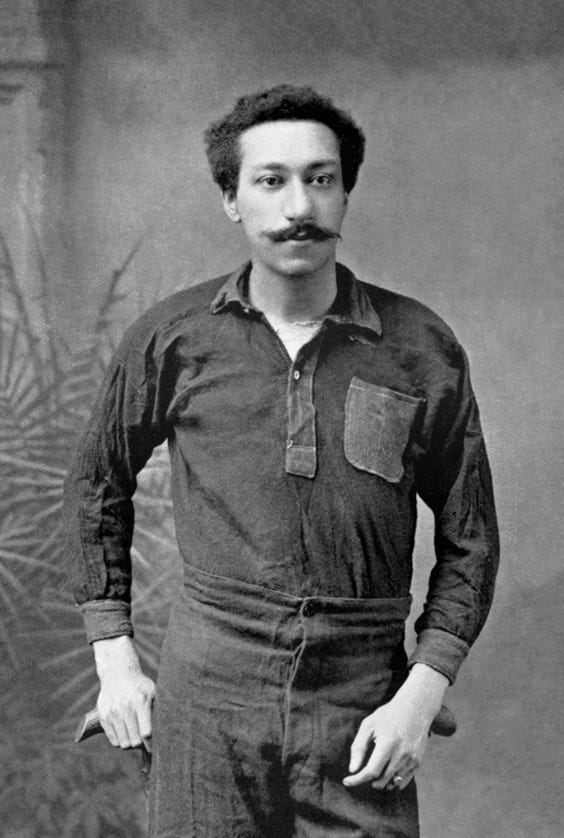

Arthur Wharton, England’s first Black Footballer

Arthur Wharton. And his moustache.

Ghanian-born Arthur Wharton was the first non-white professional footballer in England. In 1886 Preston North End Chairman Major William Sudell, another early pioneer of the game, signed Wharton to play in goal for the club. At Preston, Wharton had been part of the first club in English football to be called “The Invincibles” — a nickname earned by Preston for going unbeaten in the 1888/89 season.

Wharton left Preston to concentrate on athletics, running having always been his primary passion, but returned to the game in later life as a player-coach. It was in this role at Stalybridge Rovers in 1897 that a nineteen year old young footballer just starting out on his career came under his direction — that player was Herbert Chapman.

Although their time together would be brief (Chapman left for Rochdale a year later) Wharton’s coaching seems to have had an impact on Chapman. Many of his early innovations as a manager would draw on ideas first formulated by Sudell at Preston, and Wharton was Chapman’s first exposure to that thinking and approach. Wharton’s example as a black professional footballer, and Chapman’s daily interactions with him, can also only have helped Chapman later see Tull not as something unusual, but as just a player like any other.

Adding Bite to Northampton Town

Since being appointed Northampton Town manager in 1907 Chapman had worked hard to turn the struggling team around. That process had started at the back, tightening the defence both in terms of tactics and personnel to the point where they had finished second behind Swindon Town in the 1910/11 Southern Football League, losing only eight games all season (the lowest in the league). Alongside those eight losses, however, had been twelve draws to Swindon’s five. Northampton needed more attacking penetration, Chapman decided, and Walter Tull was the answer — a decision no doubt helped by the fact that Tull had put three goals past Northampton Town in a friendly with Spurs that year.

Tull joined Northampton in autumn 1911, Chapman having agreed to send a sizeable transfer fee and left-back Charlie Brittain the other way. Four days later Tull made his debut against Watford and his impact was instant. In his first nine games he scored twelve goals. Under his new manager’s guidance, and with his confidence restored, Tull soon established himself as both a first team regular and fan favourite. By 1914 he had amassed 110 appearances for Northampton Town and his growing reputation as an accomplished footballer led Scottish giants Glasgow Rangers to express an interest in signing the player. For Tull a bright future (and indeed a geographical reunion with his brother Edward, who had become the first non-white dentist in Britain and now lived in Glasgow) beckoned, but then war intervened.

The Football Battalion

On the 15th December 1914 at Fulham Town Hall in London a meeting was held, to which representatives from football clubs across Britain were invited. Since the beginning of the war, discussion had raged both in the papers and behind the scenes at the clubs themselves as to what role football should play in the growing conflict. On the one hand, the clubs represented an obvious source of fit and healthy men at a time when these were being called to volunteer to serve, on the other football was a favoured pastime for those already in the ranks — many of whom had written to the papers stating that coverage of matches and results from home was one of the things they looked forward to during lulls in the fighting.

Ultimately, it was decided by both the government and the clubs themselves that the pressure — both from the public and players who felt unable to volunteer due to contractual restrictions — was too much to ignore, and this meeting had been called to announce the official creation of the 17th Middlesex “Football” Battalion.

Originally it had been anticipated that attendance at Fulham would be small, so only the smaller of the halls at Fulham Town Hall had been prepared. Very quickly, however, it became clear that the arrangements were inadequate, with 400 footballers arriving en-masse shortly before the meeting began. The entire assembly was swiftly moved to the larger of the two available halls and the proceedings began.

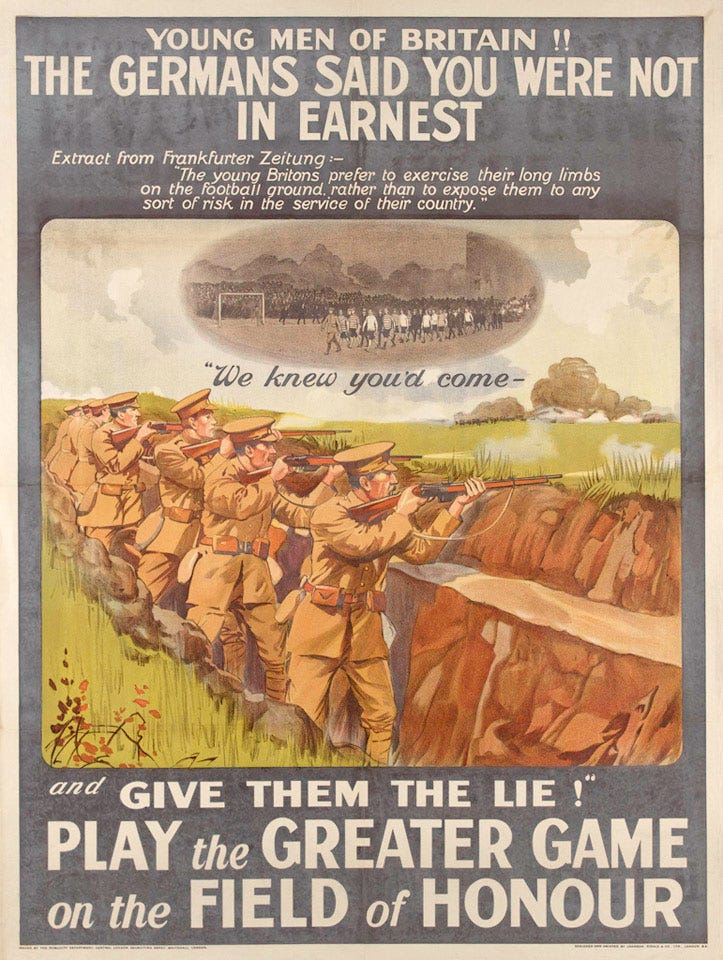

Football was a powerful recruitment and propaganda tool in WW1

On the stage at the front of the hall sat William Joynson-Hicks, MP for Brentford and the driving force behind the plan to create the Battalion. Alongside him were legendary Arsenal Chairman Henry Norris (the man responsible both for the club’s recent move to North London and their promotion to the top flight over rivals Tottenham Hotspur), Clapton (now Leyton) Orient Chairman Capt. Henry Wells-Holland and Millwall Chairman J.B Skeggs. Sharing the platform with a number of other notable figures from both football and the army, these men laid out their vision. This was for a battalion composed primarily of footballers and club staff to join the fighting, with the clubs willing to release players from their contracts where they wished to serve. The army, in turn, was willing to let those players still turn out for their clubs whilst training in Britain for combat abroad.

After the speeches were over the first call for volunteers was issued. First up on the recruiting platform was Clapton Orient captain Fred “Spider” Parker, a hugely popular figure both with fans and his fellow professionals. Archie Needham of Brighton & Hove Albion and Frank Buckley of Bradford City soon followed him up. By the end of the meeting 35 footballers had enlisted, with many more indicating that they planned to do so and agreeing to spread the word back to their clubs.

Following their captain’s lead the largest single contingent came from Clapton Orient where 41 players and staff signed up en masse. Over 300 players and club staff from across Britain would eventually serve in the battalion.

Among them was Walter who, on the 21st December 1914, became the 55th man to sign up.

First Steps into Battle

The members of the 17th Middlesex, Walter included, spent much of 1915 training in England. Initially they were based in the Machinery Hall at White City, a magnificent building left over from the 1908 Franco-British exhibition. This allowed many of the London-based players to continue to turn out for their clubs, with some players from further away (Tull included) receiving permission to make guest appearances for nearby teams such as Fulham.

Throughout this early training period Tull’s abilities as a leader began to become clear. By the time the Battalion moved to Holmbury St Mary near Dorking in April, Tull had been promoted to Lance-Corporal and by June he was a full Corporal. Indeed by the time that the Battalion received its orders to ship out to France he had reached the rank of Lance-Sergeant.

In France, both the Battalion and Tull in particular received their first blooding in combat. The British Army, its numbers boosted by volunteer battalions such as the 17th, was beginning to build up its forces in preparation for the Somme offensive of 1916. For Tull and his comrades this meant time rotating between the freezing mud of the trenches and short periods of rest and recuperation behind the lines. During these the 17th would often find itself taking part in football games against other battalions in order to boost morale. A return to the front was never far away, however, and many of the men looked to it with anticipation. As Walter himself would write home in January 1916:

For the last three weeks my Battalion has been resting some miles distant from the firing line but we are now going up to the trenches for a month or so. Afterwards we shall begin to think about coming home on leave. It is a very monotonous life out here when one is supposed to be resting and most of the boys prefer the excitement of the trenches.

The Battle of the Somme

That excitement — and unfortunately the danger that went along with it — would reach its climax for many during the Battle of the Somme, beginning 1st July 1916, in which the Football Battalion were heavily engaged. An attempt by the British to break through the German trenches in the north to relieve pressure on the French in the south, the first day of the Battle would be the bloodiest in the history of the British Army, with over 60,000 men dead or wounded.

Tull missed the opening stages of the battle. During the early days in France manning the trenches he had begun to suffer the symptoms of shell-shock and on 9th May he had been sent back to England to recover. It would mark the end of his time in the 17th Middlesex, for after recovering and being cleared to return he was sent instead to join the 23rd Middlesex. The 23rd were known as the “2nd Football,” having been raised on the same principle as the 17th.

Tull joined up with his new Battalion in September 1916 on the Somme, once again a scene of bloody fighting. He was immediately thrust into combat in the vicious Battle of Flers-Courcelette, a brutal fight in which the British attempted to take the towns of Flers and Courcelette, as well as High Wood, an area of dense trees held by the Germans since the beginning of the battle.

Aided by tanks, used in combat here for the very first time, the British were successful in securing these objectives but it came at an awful cost. Tull was in the thick of the fighting as were, a short distance away at High Wood, a number of his old comrades from the 17th. Clapton Orient players Richard McFadden, William Jonas and George Scott all died in the fighting at High Wood, and today — thanks to the efforts of Leyton Orient Supporters Club — a memorial to their deaths can be found in the churchyard at Flers.

The Clapton Orient war memorial at Flers

Having survived the vicious fighting in September, Tull was thrust into combat once again in October. A desperate and futile final attempt to break the deadlock on the Somme, The Battle of Le Transloy proved a costly failure with men and machinery bogged down and lost in the mud. Its failure marked the end of the Battle of the Somme, in which upwards of 1,000,000 men had died or been wounded.

A Pioneering Officer

Although he survived the battle, Walter did not escape entirely unscathed. In the mud and rain of the trenches he had developed “Trench Fever,” a debilitating flu-like sickness that swept through the trenches, spread by lice. He was evacuated back to England again to recover.

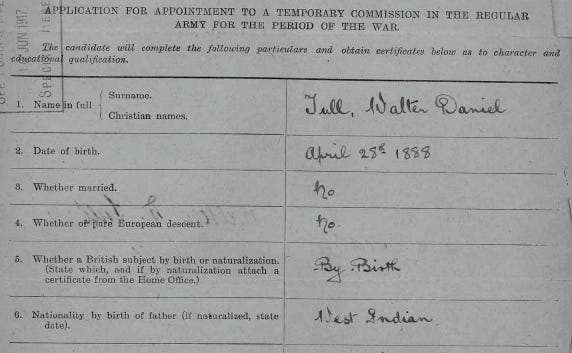

Tull’s courage and leadership under fire, however, had not gone unnoticed. Back in England he soon found himself being encouraged by the senior officers of the 23rd Middlesex to apply for a commission. Technically he should not have been able to do so. “Negros and other persons of colour” were banned from holding officer rank by Army Orders, which insisted officers should be of “pure European descent.” Without much expectation of success Tull filled out his papers anyway in November 1916.

Walter Tull’s officer application. Note his answer to the European descent question and his father’s nationality.

A month later he was shocked to receive orders to attend the Officer Cadet Training School at Gailes in Scotland. His application had been accepted. Commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in May 1917, Tull became — officially — the first black or mixed-race officer in the British Army.

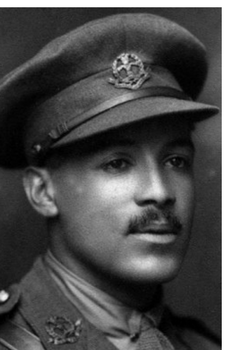

Walter in training at Gailes

Back to the Front and to Italy

Lieutenant Tull returned to the continent, and to the 23rd Middlesex, where he became a popular officer. In June 1917 he lead his men in the Battle of Messines Ridge, part of the bloody, muddy Battle of Passchendaele.

Surviving the death and destruction of Passchendaele, Lieutenant Tull and the men of the 23rd were soon ordered to Italy. On one of the forgotten fronts of WW1, the Italian Army was struggling against Germany’s allies, Austro-Hungary (in part thanks to the arrival of German troops — including a young Erwin Rommel). Despatched by the British to bolster their ally, the 23rd Middlesex, soon found themselves holding the line on the river Piave during the Battle of Caporetto. Tull and his men fought valiantly here to try and hold back the attacking German and Austrian forces, often as demoralised Italian forces melted away around them. It was here that Tull was nominated for a Military Cross for conspicuous heroism during a raid on enemy lines, although ultimately it was not awarded. As Sir Sidney Lawford, his Divisional Commander described:

You were one of the first to cross the river prior to the raid, and during the raid you took the covering party of the main body across and brought them back without a casualty in spite of heavy fire.

The failure of the army to award Tull his Military Cross was almost certainly, in part, due to his race. Indeed the anniversary of his death has brought about something of a campaign to correct this. David Lammy, MP for Tottenham has been vocal in his support of this and it would be wonderful to see Tull’s heroism finally recognised.

Walter’s Luck Runs Out

Walter in 1918

1918 saw Walter and the 23rd Middlesex back on the Western Front. Having survived the Somme, Passchendaele and Caporetto Lieutenant Tull had so far lived something of a charmed life. Sadly it was not to last.

On the 21st March 1918 the German Army began a massive offensive on the Western Front. Known as Operation Michael, it was a final attempt to win the war before the American Army arrived in force to boost the allied weight of power. Forced back by the sheer weight of fire and manpower thrown at them, British and French forces fought valiantly to prevent their retreat from turning into a rout. On the 24th March Lieutenant Tull and his men became heavily engaged with the enemy in the fighting around the town of Bapaume, from which they were forced to withdraw after nightfall.

On the 25th, near the village of Favreuil, Tull led his men in an attack on the German line. Coming under heavy machine gun fire they were forced to withdraw, but as Walter tried to cover their retreat he was shot in the head, dying instantly. Despite repeated attempts by his distraught men to recover his body, enemy fire forced them back.

Today, Walter Tull is one of many thousands of men for whom we have no known grave, his name commemorated on the memorial at Arras.

Remembering Walter Today

Walter Tull’s short life was a remarkable one. In recent years, Walter’s story has begun to attract more attention, which can only be a good thing. As an example of the contribution made by people of all colours and races to the history of Britain he stands tall. As a footballer as well as a soldier he is easy to relate to, particularly for children.

It is important, however, to remember Walter the man behind Walter the myth. A hero he most certainly was, but that is not how he would likely have seen himself. He was a footballer first and foremost, and one who had battled against issues of race on the pitch that still occasionally rear their ugly head today.

His playing career often gets skipped over in the accounts of his life that appear in the papers occasionally, which mention his time at Tottenham and Northampton Town almost in passing and often, in doing so, misattribute to him the title of “England’s first black professional footballer” — a title that actually belongs to Arthur Wharton. Wharton’s indirect influence likely helped Tull in his own battle to become seen as a player first and as a West Indian second.

This was a battle Tull was still fighting, albeit successfully, when his military career began, and perhaps one of the great tragedies is that his death meant it was a battle to which he would never get to return. Had he lived, or had the War never happened, then a transfer to Glasgow Rangers was most certainly on the cards. What new challenges and barriers that would have presented, and what effect that would have had on opportunities for non-white players in Britain we will never know. The War robbed Britain — and other countries — of a generation of young pioneers of one type or another, and Walter was one of them.

A Pioneering officer, but not necessarily the Pioneer

It is not just his football career that has often fallen victim to simplification though. As the Great War London website rightly highlights, just as Walter wasn’t the first black footballer he may well have not been the first black officer either. Research by both that website and Simon Jervis of the excellent Great War Forum has thrown up a considerable amount of evidence which suggests that this honour likely belongs to George Edward Kingsley Bemand who was commissioned in May 1915.

Lt. George Edward Kingsley Bemand. Source: Great War London

This does not detract from Walter Tull’s considerable achievement, and ultimately it is a question that comes down to semantics. Whatever the colour of his skin, Bemand did not disclose his ethnicity on his officer application and answered “yes” to the question of European descent. He likely did this with the tacit approval of his commanding officer, with the army turning a blind eye to it (if they were aware of this fudge at all). Perhaps if Bemand had answered “no” (as Walter would do in 1917) he would have been turned down at that point. Perhaps not. We will never know. He too, however, deserves to be remembered for his achievement. Recognising that doesn’t diminish Walter’s achievement. Indeed if anything it strenthens it. Walter Tull wasn’t just a pioneering black officer. He was the first one in the British Army who officially self-identified as such.

All that this highlights just how important to remember that behind the stories. Walter Tull is an icon, but this is precisely because he was a complex man and so where his life challenges and his achievements.

Walter Tull was a soldier, a leader, a hero and a bloody good footballer. So it seems fitting to end this with the words of the current Northampton Town manager, Jimmy Floyd Hasslebaink —himself a pioneering black manager — on the subject:

What he has done on the pitch opened doors for me, as a black man, to make life easier. But, also, was a role model for the white man, who he fought together with for his country.

Like what I write? Then help me do more of it. Back both me and London Reconnections, my transport site on Patreon. Every penny helps tell a story.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK