How Stoicism Became Broicism

source link: https://medium.com/@markdery/how-stoicism-became-broicism-123f3aae6aba

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

How Stoicism Became Broicism

Is it any mystery why rich tech bro’s (and their fanboys) love self-absorbed Roman philosopher-kings?

When Zeno of Citium (c. 335–263 B.C.E), the father of Stoicism, decided Providence was trying to tell him his time had come, he obligingly committed suicide — by holding his breath. Who said philosophers, famous for being long-winded, have no sense of humor?

If the gods had shown him a vision of things to come — his philosophy repurposed as “an operating system for thriving in high-stress environments” by life-hacker gurus like Tim Ferriss (The Tao of Seneca: Practical Letters from a Stoic Master) and marketers of motivational breviaries like Ryan Holiday (The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living) — he would’ve self-asphyxiated long before his preachments could get any traction with the young men of Athens.

Alas, the gods forbore, and Broicism is ascendant in Silicon Valley and wherever devotees of “peak performance” and the dude-ly gospel of success through self-mastery gather.

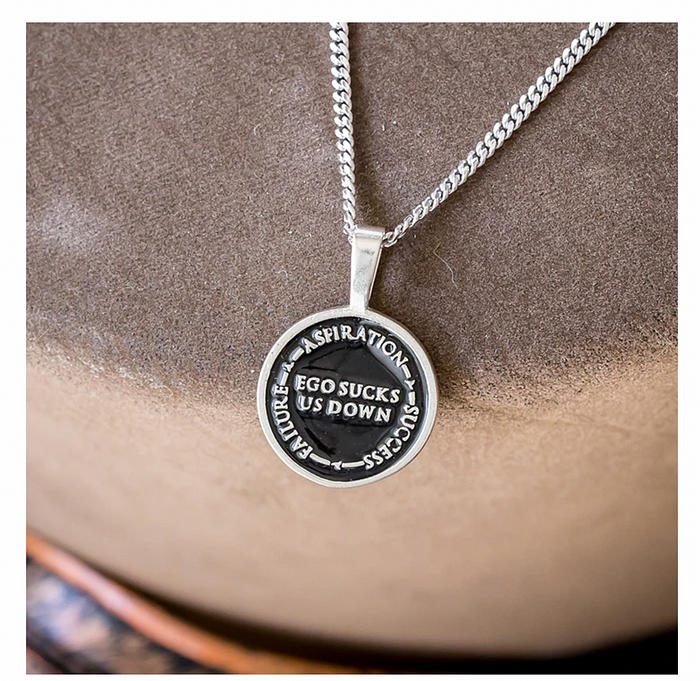

On his podcast, Ferriss retools the wisdom of Stoic philosophers like Seneca for aspiring Alpha males who dream of “rapid fat loss, incredible sex, and becoming superhuman.” Broicist titles dominate Amazon categories with Dilbert-ian names like Motivational Business Management. Holiday appears to be doing a brisk business on his Daily Stoic website, where you can buy a $50 Zippo lighter unironically inscribed with the exhortation “memento mori” (Latin for “remember that you must die,” just the thing for the chain-smoking Stoic who has everything) and a $99 sterling silver “The Ego is the Enemy” pendant whose flip side bears the stern admonition “Ego sucks us down like the law of gravity” — a quote attributed to Cyril Connolly, of all unlikely people.

(The most famously failed novelist in British letters, Connolly bemoaned his unfulfilled promise with a self-deprecating wit that’s poles apart from the slick sincerity of Broicists like Holiday. “Beneath a mask of selfish tranquility nothing exists except bitterness and boredom,” he confessed, in The Unquiet Grave. “I am one of those whom suffering has made empty and frivolous: each night in my dreams I pull the scab off a wound; each day, vacuous and habit-ridden, I help it re-form.” Too long to fit on a pendant, I’m guessing.)

Coined, apparently, by the philosophy professor Massimo Pigliucci in a 2019 post on this very platform (“$toicism, Broicism, and StoicisM”), “Broicism” has proven useful in separating the Stoics from the Broics.

Stoicism is a Greco-Roman philosophy of probity, self-restraint, self-reliance, and fatalism. Virtue is its summum bonum, its greatest good. (There’s a “a bright, shining” Daily Stoic medallion for that, too, emblazoned with the Latin phrase. Signal your Stoic virtue now, for the low, low price of $26!) “Stoicism was very much a philosophy meant to be applied to everyday living,” informsThe Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “focused on ethics (understood as the study of how to live one’s life).” Founded in Athens by Zeno circa 300 B.C.E., it arrived in Rome in 155 B.C.E., where it caught on with the patrician elite thanks to canny brand management by Cato (95–46 B.C.E.) and Seneca (4 B.C.E-65 C.E.).

Broicism is Stoicism as life hack. For tech bro’s riding a turbulent NASDAQ, it’s a philosophical stress ball, “a productivity system,” “a practical guide for entrepreneurs.” For young men who can’t get their bearings amid the crisis of masculinity and a high-tech economy where all that is solid is melting into air, it’s a “Roman” regimen for success and self-discipline.

(“Roman”-ness is part of Broicism’s allure. The Hollywood Rome of Spartacus and Gladiator has always been synonymous, in schoolboy dreams, with iron-jawed toughness and valor. In a video on his website, Holiday likens the medallions he’s hawking — overpriced “Stoic” kitsch that looks as if was turned out by the Franklin Mint, with Marcus Aurelius on quality control — to the commemorative coins “commanders of Roman legions would distribute…to their men as rewards for their service.” It’s the incurably geeky hobby of numismatics — now, with 100% more Roman Testosterone Support!)

Philosophers and Roman historians ding Broicism for dumbing Stoicism down and repackaging its maxims as daily affirmations for the “well-educated, tech-savvy, and action-oriented” — and 75% male — demographic that flocks to Ferriss’s podcast. Pigliucci, himself a card-carrying Stoic, rightly decries Broicism for its willful misreading of Stoicism as a “philosophical foundation for ‘men’s rights’ nonsense.”

His takedown of Broicism is every bit as trenchant as one would expect from a professor of philosophy. But he neglects to mention one of the ways in which Broicism is true to Stoicism, perhaps because his inner Stoic turns a blind eye on that defect. In its interminable self-absorption, Broicism is Seneca’s late-capitalist stepchild, taking (though, admittedly, it takes the Stoic’s cultivation of the Best Version of Himself to solipsistic extremes).

The Stoic ideal is radically self-centered,” writes the classics scholar D. A. Rees in his introduction to the Everyman’s Library edition of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations. “One’s concern is with one’s own thoughts, with one’s own moral purpose… The Stoic’s exclusive concentration upon morality leaves little place, save where they have direct moral relevance, for knowledge, for art, for affection, for freedom from suffering; Marcus, for all his devotion to duty, inhabits a sad and colorless world…in which there neither is nor could be any…vision of social progress…

Stoicism was born in an Athens turned upside down by the invading Macedonians, who converted the democratic city-state, at swordpoint, into an oligarchy and restricted the right to vote to property owners, disenfranchising two-thirds of the citizens. It went viral in a Rome that had witnessed its Republic overthrown, after the murder of Julius Caesar, and replaced by an autocracy ruled by emperors corrupted absolutely by absolute power — monsters of depravity like Nero, whom Seneca tutored — and destabilized by palace intrigue. Imagine the Trump White House with togas and a less welcoming attitude toward Christians, who tended to be used as charcoal briquets in auto-da-fés.

In turbulent times like Zeno’s or Seneca’s or ours, Stoicism’s attractions are obvious: it builds a bulwark around the self and counsels equanimity in the face of forces beyond one’s control. Retreat into the monastery of the mind, it urges, where “one’s concern is with one’s own thoughts, with one’s own moral purpose.” It’s the perfect fit for the “radically self-centered”: never-ending self-improvers like Ferriss, the millionaire pitchman for personal growth; masters of the metaverse like Mark Zuckerberg.

Recently, Ferriss interviewed Zuckerberg on The Tim Ferriss Show. I clicked play, curious to know what a practicing Stoic who’s given sober thought to his moral purpose would ask a conscienceless billionaire, a 37-year-old man-boy who always reminds me of Nero, at 16 the absolute ruler of the known world. He’s even got that imperial haircut familiar from marble busts, although he wears his in the Caligulan, not the Neronian, style, with that little fringe of a bang.

The probing questions never come. Nothing but softballs from Ferriss, with a side serving of fulsome praise.

Zuckerberg speaks in that curious patois, equal parts technobabble, corporate buzzwordery, and mission-statement platitude, that comes naturally to Silicon Valley’s ruling class. Talking about the role of religion in his life, he offers this takeaway from his Talmudic study of the Book of Genesis: “A lot of what we are here to do is create good things in the world…build things that make the world better.” Facebook, the listener realizes — with a shudder — is Zuckerberg’s idea of a good thing that makes the world better.

At one point, he laments, “The last five or six years have been pretty tough. If you just look at how people felt about our company before 2016 … there was almost never a month when the sentiment was negative. Since 2016, there’s almost never been a month where the net sentiment has been positive.”

But, by Cloudy Zeus’s tunic, he’s philosophical, one might even say stoic. “There just need to be things that are bigger than you in your life,” he says. “Even though our country has a lot of struggles, I probably believe more in democracy now than I would’ve.” (See what he did there, equating Facebook’s self-inflicted brand damage with the mortal wounds, to American democracy, of social, racial, and economic injustice? What’s bad for Facebook is bad for America!) “I probably didn’t think about it that deeply before, but I just think believing in democracy, in our institutions, is sort of a bigger force than any individual.”

The man whose social-media platform is a petri dish for culturing conspiracy theories, insurrectionist plots, anti-vaxxer misinformation, and bigotry so vile it beggars description; the man who has done more, arguably, than any other god-emperor in Silicon Valley to undermine democratic institutions, and done it in pursuit of no greater good than profit maximization, believes devoutly in democracy?

I wait for Ferriss to slip the knife in, wishful thinking on this old cynic’s part. (How did that pocket of naïveté escape eradication?) Of course, he never does, because Stoic rectitude is a personal matter, between yourself and the divine reason that pervades all nature. (At least, that’s how Zeno saw it; for Broics, whose manuals and medallions make no mention of any power higher than You, virtue is between yourself and yourself. In practice, the Broicist motto isn’t “the ego is the enemy” but “solus ipse,” Latin for “the self alone,” from which we get “solipsism.”)

Then, too, calling out your fellow plutocrats for their moral turpitude is bad form, not to mention bad for business. (Now might be the time to mention that Ferriss invested in Meta, the new, more futurrific Facebook.) Stoicism has no quarrel with capitalism and, while preaching civic virtue — useful for emperors like Marcus Aurelius and counselors to emperors like Seneca — it advises resignation, not revolution, in the face of injustice and oppression. But what’s the point of cultivating moral wisdom if you’re never moved to action? Ferriss and his fans are “action-oriented,” but not, apparently, when it comes to social responsibility.

I’m reminded of the deliriously wealthy Seneca, who frowned on the pursuit of wealth and reassured Lucilius, in his Moral Letters, that “the successful are of all men most miserable” (a pronouncement that would come as a shock to bro’s who regard Stoicism as an “operating system” for success without stress). Yet he amassed a vast fortune by lending money to Britons at extortionate rates. His false virtue earned him a public rebuke from the senator Publius Suilius, who excoriated him as a “hypocrite … who denounces wealth, and sucks the provinces dry by usury.”

I’m reminded, too, of Seneca coaching Nero in the Stoic catechism, schooling him in anger management, clemency, the tranquility of the soul, the brevity of life— and of how well that worked out. Ah, well: “The one class is born to obey, the other to command,” Seneca writes, in De Constantia Sapientis (“On the Firmness of the Wise”), with Stoic imperturbability.

Stoicism, as Rees notes, gives no thought to social progress. Snug in its fortress of elite privilege and airy unconcern, the Stoic self abandons all hope in movement politics or solidarity with the less fortunate. It makes a religion of self-absorption while the world burns. Its homilies are Seneca’s, but its soundtrack is Nero’s fiddle.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK