The State of JavaScript in 2018

source link: https://www.breck-mckye.com/blog/2017/12/The-State-of-JavaScript-in-2018/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

The State of JavaScript in 2018

Fri Dec 29 2017

Three years ago, I wrote The State of JavaScript in 2015. In it I claimed the rapid pace of change in our industry required us to adopt “microlibraries” - replacing monolithic frameworks with small, thin, single-purpose libraries. But now I’ve changed my mind.

My argument is twofold. Firstly, microlibrary architectures have costs that I feel too few openly acknowledge. They require glue code, decision making, configuration and risk-taking that all take their toll on productivity. Secondly, these costs are no longer necessary: the JS ecosystem has slowed down, practices have settled, and web applications are becoming more and more alike. When development practices converge, frameworks can make useful assumptions about our projects.

By the end of this post I hope to convince you that “batteries-included” frameworks aren’t just a better choice - they’re actually an economic necessity.

First, some context.

The State of JavaScript in 2015

When I last wrote, Google had just announced that Angular 2 would be a backwards-incompatible rewrite of the entire framework. If you were a 2013 NG-convert, you had just invested a year of work into a technology that was suddenly obsolete. This went down about as well as you might expect.

In this context, I made two (rather guarded) predictions:

One, that the rate of change in the JavaScript ecosystem was unsustainable, that developers would backlash against it, and -

Two: to protect themselves from framework obsolescence, developers would invest in microlibraries - small, single-purpose libraries with simple APIs that required little framework-specific “proprietary” knowledge.

Though I flatter myself, I do think that’s more or less what happened. Firstly, the webdev community began to call out JavaScript “churn”; and secondly, they adopted React, which it turned out had really been a microlibrary all along.

That might sound odd, given how large React’s codebase is. But like a microlibrary, React concerns itself with solving only one problem, well: writing views as functions. It did that with an extremely thin templating language (JSX) that introduces as little template syntax as it can get away with. Because React is “just JavaScript”, developers spend minimal energy on library-specific concepts. It might not be “micro” in terms of bytes-down-the-wire, but it’s certainly a low-risk investment that makes sense at a time of churn.

Almost all React projects follow this microlibrary architecture: pulling in a diverse array of plugins and utils to help with state (Redux, Sagas), routing (React-Router), collections (Lodash), immutability (Immutable.js) and no doubt others that have slipped my memory. I mean them no slur by omitting them. Likewise, the build scripts of these projects are powered by a basket of Webpack and Babel plugins, all carefully threaded together with configuration files.

So far the React stack has served us rather well. Individual components have been experimented with and replaced as practices have evolved - like the various incarnations of Flux, or multiple iterations of React-Router - but without requiring project rewrites. Similarly Webpack has allowed us to quickly adopt new techniques such as transpilation, experimental JS, split bundling and scoped CSS just by adding NPM plugins as they are invented (at least, that’s the theory).

The problem is, the world has changed, but our application stack is still stuck in 2015. I think this is holding us back.

The costs of microlibraries in 2018

When we adopted the microlib architecture, we made certain tradeoffs.

For one thing, using lots of dependencies means making lots of dependency decisions. What used to be a once-per-project task is now something we might do every week.

It’s easy to choose a JavaScript library, but hard to choose one well. Most developers use popularity as a proxy for quality. They hope that if a project has a thousand stars on Github, it will never be replaced, never introduce breaking changes, nor ever introduce vulnerabilities to your project.

This can’t be guaranteed though, and I don’t need to recall the left-pad fiasco to demonstrate how. Just look at your own projects and count the dependencies. How many of these have you subjected to a security audit? How many have you performance tested? How many do you know have stable leadership? With so many, how could you?

David Gilbertson wrote a very fine article on Hackernoon a few weeks since: I’m harvesting credit card numbers and passwords from your site. Here’s how. It’s a piece of fiction about a piece of malware snook into a popular NPM package. You can’t spot it in your network tools, because it detects Chrome devtools. You can’t spot it by eyeballing your bundle, because the HTTP request is obfuscated. You can’t even look the package up on Github, because the NPM version is subtly different. You’re out of luck, and even if someone did sniff it out, it’d be too late: with developers “installing npm packages like they’re popping pain killers”, by the time any alert came the malware would already be packaged into thousands and thousands of downstream websites.

The moral of the story is supposedly not to install third-party code onto sensitive pages, but I have another take. It’s not that humans are careless or lazy, so much as that the systems we’ve built to support our microlibrary stack make it harder to build robust and secure systems. A combination of technologies: NPM, Github, beautiful READMEs - warp our decision-making, enable hasty decisions and encourage us to npm install first, ask questions later.

And that’s the real state of JavaScript in 2018: no due diligence and fragile dependency trees, not because developers are dumb but because microlibs require careful decision-making at odds with the pace of most technology companies.

Boilerplates are the wrong solution to the right problem

Now, one innovation - and potential solution - that’s gone curiously unnoted these last few years has been the rise of JavaScript boilerplates. These projects, usually hosted on Github, provide example code for building a microlibrary architecture web project. They will pull together a React stack with a Webpack / Babel build system and often some kind of preproduction server. They are very, very popular, too: the original React-Boilerplate has close to 17,000 Github stars.

I have never been comfortable with this; I like to understand all the components of my application stack so that I know I can always pull myself out of a crisis. This matters particularly to build scripts: I’ve worked on too many projects where no-one properly knew how the Webpack or Gulp setup actually functioned, how the code was actually packaged up for deployment. Things go fine… until the first time they don’t, usually in the midst of some production issue nightmare.

But they do demonstrate a real need: developers do not want to spend the first weeks of their projects picking out microlibraries and writing glue code. They would much rather install an environment like Create-React-App that provides not only an application boilerplate, but tools to scaffold the project, reformat the code, and even configure a Continuous Integration process.

As powerful as systems like CRA may be, though, they will always be hampered by the fact they cannot truly control their dependencies. If React-Router-5 rolls out a brand new roster of breaking changes, CRA must pass them on to its own users. If a dependency gets withdrawn due to a legal or intellectual property dispute (like left-pad), CRA ultimately has to drop it also. Boilerplate authors can’t totally insulate their users from the costs of microlibraries.

Benefits of monoliths

So far I’ve written mostly on the costs of building a project from small, single-purpose libraries. But I haven’t explained what monoliths can specifically gain us.

In summary: monolithic frameworks provide a unified experience that is abstracted away from the underlying technology. This allows them to create domain-specific-languages and “framework magic” that trade transparency for productivity.

For example, in the original Angular, developers wrote views in an Angular-specific template language. This would cleverly wire up the view to a state object in the background, known as a controller:

<label>Click me:

<input type="checkbox" ng-model="checked" ng-init="checked=true" />

</label>

<br/>

Show when checked:

<span ng-if="checked">

This is removed when the checkbox is unchecked.

</span>

The magic happens in the ng- attributes, which are of course alien to HTML. I call them ‘magic’ because whilst powerful, they are quite hard to reason about. What exactly is Angular doing when it encounters that incantation? And like magic spells, they are something I have to learn and memorise. If the framework becomes obsolete, that learning is wasted.

Compare that to the equivalent JSX:

onChange(e) {

this.setState({checked: e.target.checked});

}

render() {

return (<div>

<label>Click me:

<input

type="checkbox"

onChange={this.onChange.bind(this)}

checked={this.state.checked}

/>

</label>

<br/>

Show when checked:

{this.state.checked &&

<span>

This is removed when the checkbox is unchecked.

</span>

}

</div>

);

}

As you can see, JSX is much more transparent - it’s far closer to real JavaScript, and it has almost no special HTML syntax except the curly braces used for expressions ({}). But - and this is a big but - what it trades away is productivity. It’s more verbose. You have to deal with things like JavaScript function binding and raw DOM event APIs (e.target et al). It can make no assumptions about how state is managed globally, outside the individual component.

Things like JSX make sense when the technology is unstable. You don’t want to learn template syntax and library-specific “spells” when the framework might be obsolete in under a year. But outside of those conditions, those thin abstractions hold you back as a programmer. JSX has lots of compelling features - the fact you can stick debug breakpoints in it for one - but I think it’s held back by its conservatism.

Monoliths have other benefits, too. They are well-documented and provide a single target for developer effort. They can make useful assumptions about the nature of your project. They establish a standard technology that makes it easier for programmers to move jobs, and likewise easier to hire replacements.

Won’t I get burned by churn?

No, because despite the ubiquitous background radiation of r/programming memes and complaints on Hacker News, the JavaScript ecosystem has actually cooled a great deal these last two years.

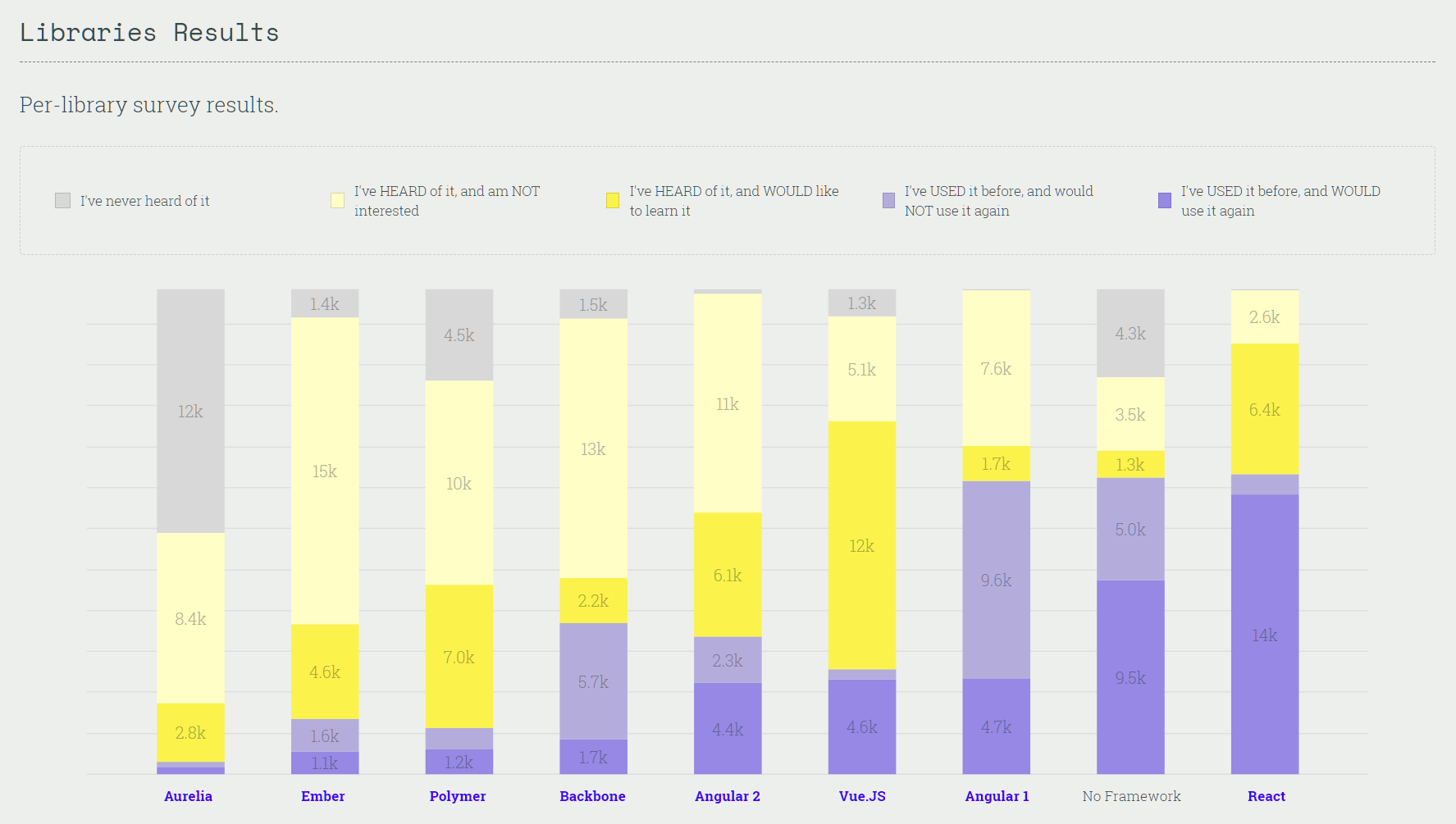

Consider this slide from the State of JS 2017 survey (namesake coincidental):

Assuming the survey is representative, these are the most common front-end JavaScript libraries currently in use. Only one of them is less than two years old:

- React, released March 2015

- Angular 1, released October 2010

- Angular 2, released December 2015

- Vue, released October 2015

- Backbone, released October 2010

- Ember, released December 2011

- Aurelia, released June 2016

It’s not just the technologies that have converged, either: the paradigms have too. The everyday practices of web developers just aren’t changing much any more. Practically all projects run ES6 code through a Webpack-Babel transpilation machine. They output split bundles with a common vendor file. Files have hashes in their names for cache-busting. JSX or Vuefile compilation is a standard.

And yet all these projects maintain the same hulking messes of webpack config files, stringing together countless micro-dependencies. Our tooling grants us this marvellous flexibility and a dizzying array of choices, but do we even need them?

But there’s another, chillier factor at play here: the web itself has stalled. We’ve been so excited by all the innovation in JavaScript land that we haven’t noticed how homogenous web applications have become.

By this, I mean that the types of websites we build aren’t terribly varied. My experience is that through my career I’ve only ever really built two kinds of JavaScript application: content sites funded by adverts, or SPAs that front some physical service. The latter always comprise list pages, big tables with sortable columns, and maps. If I’m lucky I get to animate a donut chart. It’s quite uncanny how similar these apps have been, despite being built for completely different companies operating in completely different industries.

There might be few reasons why this has happened. One is that it’s very hard right now to monetize pure web content - articles, media or desktop app replacements - because ad revenue, which was always low, has been hoovered up by Google and Facebook, between them consuming almost 65% of digital ad spend.

Another possible reason is that new web APIs are not being adopted by browser vendors in a consistent fashion, which ultimately holds back what JS apps can even do. Apple in particular resists change, in part because the richer web applications become, the less incentive there is to develop for the App Store.

Ultimately what matters is not the cause but the effect: in 2018, we will generally be building the same kinds of webapps for the same kinds of companies. In this kind of environment, economics dictates that we move away from ‘exploration’ - experimenting with new practices, paradigms, technologies - and towards ‘exploitation’ instead: building similar things faster and cheaper.

And that’s where monoliths have the advantage. Large frameworks can make assumptions about the kinds of applications we’re building, and make those usecases the default choice. They can provide a wealth of tutorials and example code for those common website designs. Deflating as it may sound, what our projects need right now isn’t flexibility, but a way to cut the excessive costs of developing for the web.

What does this mean?

Before concluding, I’d like to take a moment to say what this post is not.

It is not an outright rejection of microlibraries. On the contrary, if you’re building a content site that needs to render in one second on mobile, and microlibs get you within the golden 14kb SYN/ACK window, definitely go use them.

It is also not an attack on React. I think pure components and the virtual DOM are very important ideas. I just think that in the future we’ll be using thicker abstractions than ‘vanilla React’. Those might be wrapper frameworks that abstract over routing and state management, or they could be something simpler, closer to Create-React-App.

What I _am_ saying is that over the next few years, I think the patchwork architectures of microlibraries we’ve grown will be gradually replaced by technologies that formalise these choices. They will take a convention-over-configuration approach and will trade transparency for productivity.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK