Swift Logging - NSHipster

source link: https://nshipster.com/swift-log/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Swift Logging

In 2002, the United States Congress enacted the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, which introduced broad oversight to corporations in response to accounting scandals at companies like Enron and MCI WorldCom around that time. This act, PCI and HIPAA , formed the regulatory backdrop for a new generation of IT companies emerging from the dot-com bubble.

Around the same time, we saw the emergence of ephemeral, distributed infrastructure — what we now call “Cloud computing” — a paradigm that made systems more capable but also more complex.

To solve both the regulatory and logistical challenges of the 21st century, our field established best practices around application logging. And many of the same tools and standards are still in use today.

Just as print is a poor man’s debugger,

it’s also a shallow replacement for a proper logging system,

with distinct log levels and configurable output settings.

Sarbanes–Oxley is notable for giving rise to Yates v. United States: a delightful Supreme Court case that asked the question _“Are fish (?) tangible objects?”

Although the Court found in a 5 – 4 decision that fish are not, in fact, “tangible objects” (for purposes of the statute), we remain unconvinced for the same reasons articulated in Justice Kagan’s dissent (and pretty much anything written by Claude Shannon, for that matter).

This week on NSHipster,

we’re taking a look at

SwiftLog:

a community-driven, open-source standard for logging in Swift.

Developed by the Swift on Server community

and endorsed by the

SSWG (Swift Server Work Group),

its benefit isn’t limited to use on the server.

Indeed,

any Swift code intended to be run from the command line

would benefit from adopting SwiftLog.

Read on to learn how.

SwiftLog is distinct from the

Unified Logging System

(os_log),

which is specific to Apple platforms.

Readers may already be familiar with os_log and its, *ahem*

quirks

(a topic for a future article, perhaps).

But for the uninitiated,

all you need to know is that

os_log is for macOS and iOS apps and

SwiftLog is for everything else.

If you’re interested in learning more about Unified Logging,

you can get a quick overview of

by skimming the os_log docs;

for an in-depth look,

check out

“Unified Logging and Activity Tracing”

from WWDC 2016

and

“Measuring Performance Using Logging”

from WWDC 2018.

As always, an example would be helpful in guiding our discussion. In the spirit of transparency and nostalgia, let’s imagine writing a Swift program that audits the finances of a ’00s Fortune 500 company.

import Foundation

struct Auditor {

func watch(_ directory: URL) throws { … }

func cleanup() { … }

}

do {

let auditor = Auditor()

defer { auditor.cleanup() }

try auditor.watch(directory: URL(string: "ftp://…/reports")!,

extensions: ["xls", "ods", "qdf"]) // poll for changes

} catch {

print("error: \(error)")

}

An Auditor type polls for changes to a directory

(an FTP server, because remember: it’s 2003).

Each time a file is added, removed, or changed,

its contents are audited for discrepancies.

If any financial oddities are encountered,

they’re logged using the print function.

The same goes for issues connecting to the FTP,

or any other problems the program might encounter —

everything’s logged using print.

The implementation details aren’t important; only the interface is relevant to our discussion.

Simple enough. We can run it from the command line like so:

$ swift run audit

starting up...

ERROR: unable to reconnect to FTP

# (try again after restarting PC under our desk)

$ swift run audit

+ connected to FTP server

! accounting discrepancy in balance sheet

** Quicken database corruption! **

^C

shutting down...

Such a program might be technically compliant, but it leaves a lot of room for improvement:

- For one, our output doesn’t have any timestamps associated with it. There’s no way to know whether a problem was detected an hour ago or last week.

- Another problem is that our output lacks any coherent structure. At a glance, there’s no straightforward way to isolate program noise from real issues.

- Finally, — and this is mostly due to an under-specified example — it’s unclear how this output is handled. Where is this output going? How is it collected, aggregated, and analyzed?

The good news is that all of these problems (and many others) can be solved by adopting a formal logging infrastructure in your project.

Adopting SwiftLog in Your Swift Program

Adding SwiftLog to an existing Swift package is a breeze.

You can incorporate it incrementally

without making any fundamental changes to your code

and have it working in a matter of minutes.

Add swift-log as a Package Dependency

In your Package.swift manifest,

add swift-log as a package dependency and

add the Logging module to your target’s list of dependencies.

// swift-tools-version:5.1

import PackageDescription

let package = Package(

name: "Auditor2000",

products: [

.executable(name: "audit", targets: ["audit"])

],

dependencies: [

.package(url: "https://github.com/apple/swift-log.git", from: "1.2.0"),

],

targets: [

.target(name: "audit", dependencies: ["Logging"])

]

)

Create a Shared, Global Logger

Logger provides two initializers,

the simpler of them taking a single label parameter:

let logger = Logger(label: "com.NSHipster.Auditor2000")

In POSIX systems, programs operate on three, predefined streams:

File Handle Description Name

0

stdin

Standard Input

1

stdout

Standard Output

2

stderr

Standard Error

By default,

Logger uses the built-in StreamLogHandler type

to write logged messages to standard output (stdout).

We can override this behavior to instead write to standard error (stderr)

by using the more complex initializer,

which takes a factory parameter:

a closure that takes a single String parameter (the label)

and returns an object conforming to LogHandler.

let logger = Logger(label: "com.NSHipster.Auditor2000",

factory: StreamLogHandler.standardError)

Alternatively,

you can set default logger globally

using the LoggingSystem.bootstrap() method.

LoggingSystem.bootstrap(StreamLogHandler.standardError)

let logger = Logger(label: "com.NSHipster.Auditor2000")

After doing this,

any subsequent Logger instances created

using the Logger(label:) initializer

will default to the specified handler.

Replacing Print Statements with Logging Statements

Declaring our logger as a top-level constant

lets us call it anywhere within our module.

Let’s revisit our example and spruce it up with our new logger:

do {

let auditor = Auditor()

defer {

logger.trace("Shutting down")

auditor.cleanup()

}

logger.trace("Starting up")

try auditor.watch(directory: URL(string: "ftp://…/reports")!,

extensions: ["xls", "ods", "qdf"]) // poll for changes

} catch {

logger.critical("\(error)")

}

The trace, debug, and critical methods

log a message at their respective log level.

SwiftLog defines seven levels,

ranked in ascending order of severity from trace to critical:

Level Description

.trace

Appropriate for messages that contain information only when debugging a program.

.debug

Appropriate for messages that contain information normally of use only when debugging a program.

.info

Appropriate for informational messages.

.notice

Appropriate for conditions that are not error conditions, but that may require special handling.

.warning

Appropriate for messages that are not error conditions, but more severe than .notice

.error

Appropriate for error conditions.

.critical

Appropriate for critical error conditions that usually require immediate attention.

If we re-run our audit example with our new logging framework in place,

we can see the immediate benefit of clearly-labeled, distinct severity levels

in log lines:

$ swift run audit

2020-03-26T09:40:10-0700 critical: Couldn't connect to ftp://…

# (try again after plugging in loose ethernet cord)

$ swift run audit

2020-03-26T10:21:22-0700 warning: Discrepancy in balance sheet

2020-03-26T10:21:22-0700 error: Quicken database corruption

^C

Beyond merely labeling messages,

which — don’t get us wrong — is sufficient benefit on its own,

log levels provide a configurable level of disclosure.

Notice that the messages logged with the trace method

don’t appear in the example output.

That’s because Logger defaults to showing only messages

logged as info level or higher.

You can configure that by setting the Logger’s logLevel property.

var logger = Logger(label: "com.NSHipster.Auditor2000")

logger.logLevel = .trace

After making this change, the example output would instead look something like this:

$ swift run audit

2020-03-25T09:40:00-0700 trace: Starting up

2020-03-26T09:40:10-0700 critical: Couldn't connect to ftp://…

2020-03-25T09:40:11-0700 trace: Shutting down

# (try again after plugging in loose ethernet cord)

$ swift run audit

2020-03-25T09:41:00-0700 trace: Starting up

2020-03-26T09:41:01-0700 debug: Connected to ftp://…/reports

2020-03-26T09:41:01-0700 debug: Watching file extensions ["xls", "ods", "qdf"]

2020-03-26T10:21:22-0700 warning: Discrepancy in balance sheet

2020-03-26T10:21:22-0700 error: Quicken database corruption

^C

2020-03-26T10:30:00-0700 trace: Shutting down

Using Multiple Logging Handlers at Once

Thinking back to our objections in the original example, the only remaining concern is what we actually do with these logs.

According to 12 Factor App principles:

XI. Logs

[…]

A twelve-factor app never concerns itself with routing or storage of its output stream. It should not attempt to write to or manage logfiles. Instead, each running process writes its event stream, unbuffered, to

stdout.

Collecting, routing, indexing, and analyzing logs across a distributed system often requires a constellation of open-source libraries and commercial products. Fortunately, most of these components traffic in a shared currency of syslog messages — and thanks to this package by Ian Partridge, Swift can, as well.

That said, few engineers have managed to retrieve this information from the likes of Splunk and lived to tell the tale. For us mere mortals, we might prefer this package by Will Lisac, which sends log messages to Slack.

The good news is that we can use both at once,

without changing how messages are logged at the call site

by using another piece of the Logging module:

MultiplexLogHandler.

import struct Foundation.ProcessInfo

import Logging

import LoggingSyslog

import LoggingSlack

LoggingSystem.bootstrap { label in

let webhookURL = URL(string:

ProcessInfo.processInfo.environment["SLACK_LOGGING_WEBHOOK_URL"]!

)!

var slackHandler = SlackLogHandler(label: label, webhookURL: webhookURL)

slackHandler.logLevel = .critical

let syslogHandler = SyslogLogHandler(label: label)

return MultiplexLogHandler([

syslogHandler,

slackHandler

])

}

let logger = Logger(label: "com.NSHipster.Auditor2000")

Harkening to another 12 Factor principle, we pull the webhook URL from an environment variable rather than hard-coding it.

With all of this in place,

our system will log everything in syslog format to standard out (stdout),

where it can be collected and analyzed by some other system.

But the real strength of this approach to logging

is that it can be extended to meet the specific needs of any environment.

Instead of writing syslog to stdout or Slack messages,

your system could send emails,

open SalesForce tickets,

or trigger a webhook to activate some

IoT device.

Granted, each of those examples would probably be better served by a separate monitoring service that ingests a log stream and reacts to events according to a more elaborate set of rules.

Here’s how you can extend SwiftLog to fit your needs

by writing a custom log handler:

Creating a Custom Log Handler

The LogHandler protocol specifies the requirements for types

that can be registered as message handlers by Logger:

protocol LogHandler {

subscript(metadataKey _: String) -> Logger.Metadata.Value? { get set }

var metadata: Logger.Metadata { get set }

var logLevel: Logger.Level { get set }

func log(level: Logger.Level,

message: Logger.Message,

metadata: Logger.Metadata?,

file: String, function: String, line: UInt)

}

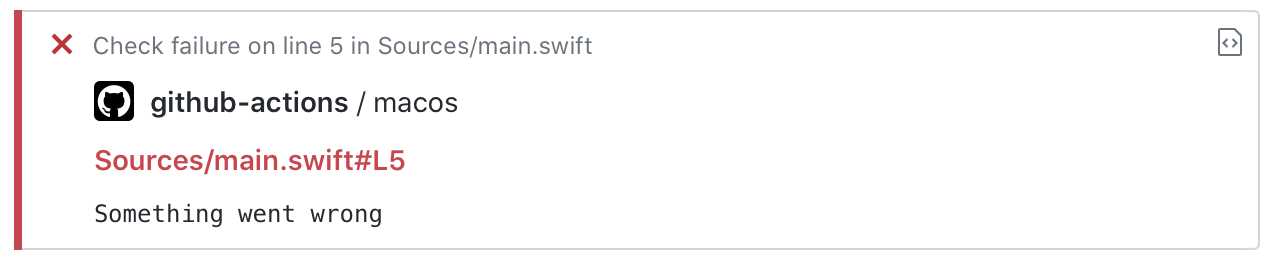

In the process of writing this article, I created custom handler that formats log messages for GitHub Actions so that they’re surfaced on GitHub’s UI like so:

For more information, see “Workflow commands for GitHub Actions.”

If you’re interested in making your own logging handler, you can learn a lot by just browsing the code for this project. But I did want to call out a few points of interest here:

Conditional Boostrapping

When bootstrapping your logging system, you can define some logic for how things are configured. For logging formatters specific to a particular CI vendor, for example, you might check the environment to see if you’re running locally or on CI and adjust accordingly.

import Logging

import LoggingGitHubActions

import struct Foundation.ProcessInfo

LoggingSystem.bootstrap { label in

// Are we running in a GitHub Actions workflow?

if ProcessInfo.processInfo.environment["GITHUB_ACTIONS"] == "true" {

return GitHubActionsLogHandler.standardOutput(label: label)

} else {

return StreamLogHandler.standardOutput(label: label)

}

}

Testing Custom Log Handlers

Testing turned out to be more of a challenge than originally anticipated. I could be missing something obvious, but there doesn’t seem to be a way to create assertions about text written to standard output. So here’s what I did instead:

First,

create an internal initializer that takes a TextOutputStream parameter,

and store it in a private property.

Swift symbols have internal access control by default;

the keyword is included here for clarity.

public struct GitHubActionsLogHandler: LogHandler {

private var outputStream: TextOutputStream

internal init(outputStream: TextOutputStream) {

self.outputStream = outputStream

}

…

}

Then,

in the test target,

create a type that adopts TextOutputStream

and collects logged messages to a stored property

for later inspection.

By using a

@testable import

of the module declaring GitHubActionsLogHandler,

we can access that internal initializer from before,

and pass an instance of MockTextOutputStream to intercept logged messages.

import Logging

@testable import LoggingGitHubActions

final class MockTextOutputStream: TextOutputStream {

public private(set) var lines: [String] = []

public init(_ body: (Logger) -> Void) {

let logger = Logger(label: #file) { label in

GitHubActionsLogHandler(outputStream: self)

}

body(logger)

}

// MARK: - TextOutputStream

func write(_ string: String) {

lines.append(string)

}

}

With these pieces in place, we can finally test that our handler works as expected:

func testLogging() {

var logLevel: Logger.Level?

let expectation = MockTextOutputStream { logger in

logLevel = logger.handler.logLevel

logger.trace("?")

logger.error("?")

}

XCTAssertGreaterThan(logLevel!, .trace)

XCTAssertEqual(expectation.lines.count, 1) // trace log is ignored

XCTAssertTrue(expectation.lines[0].hasPrefix("::error "))

XCTAssertTrue(expectation.lines[0].hasSuffix("::?"))

}

As to how or where messages are logged,

SwiftLog is surprisingly tight-lipped.

There’s an internal type that buffers writes to stdout,

but it’s not exposed by the module.

If you’re in search for a replacement and would prefer not to copy-paste something as involved as that, here’s a dead-simple alternative:

struct StandardTextOutputStream: TextOutputStream {

mutating func write(_ string: String) {

print(string)

}

}

Recommend

-

42

42

原文: NSRegularExpression 原作者:Nate Cook 遇到问题,哦,要用NSRegularExpression了。其实呢,有一些,是要注意的。 正则表达式是一种DSL, 有一些讨论。说他不好,毕竟Regex里面都是各种符号。说他好,Regex简明强大,用途广泛。 公认的是,Cocoa 给NSRegu...

-

54

54

README.md AVSpeechSynthesizer Example A companion project to the NSHipster article about AVSpeechS...

-

28

28

README.md macOS Dynamic Desktop Sample Code Companion playgrounds to the NSHipster article about...

-

46

46

README.md swift-gyb Evaluates and runs a Swift GYB script. Disclaimer

-

76

76

README.md swift-format swift-format formats and diagnoses Swift source code according to a set of style guidelines. It can be used as a

-

36

36

README.md DBSCAN

-

14

14

AVSpeechSynthesizer - NSHipsterThough we’re a long way off from Hal or Her,...

-

8

8

Dangerous Logging in SwiftI recently came across a perplexing crash in my unit tests that led me down a path of discovery, culminating in an awareness that “I was holding it wrong” when it comes to using NSLog in Swift. Here is the sou...

-

4

4

Exporting data from Unified Logging System in Swift 19 Apr 2022 We discussed building a proper logging system instead of using the print function in the previous post. Apple provides us a framework to utilize its logging system b...

-

5

5

AWS Amplify enables CloudWatch Logging Support for Swift and Android by Abdallah Shaban | on 02 AUG 2023 | in

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK