When to use a DI Container

source link: https://blog.ploeh.dk/2012/11/06/WhentouseaDIContainer/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

When to use a DI Container

This post explains why a DI Container is useful with Convention over Configuration while Poor Man's DI might be a better fit for a more explicit Composition Root.

Note (2018-07-18): Since I wrote this article, I've retired the term Poor Man's DI in favour of Pure DI.

It seems to me that lately there's been a backlash against DI Containers among alpha geeks. Many of the software leaders that I myself learn from seem to dismiss the entire concept of a DI Container, claiming that it's too complex, too 'magical', that it isn't a good architectural pattern, or that the derived value doesn't warrant the 'cost' (most, if not all, DI Containers are open source, so they are free in a monetary sense, but there's always a cost in learning curve etc.).

This must have caused Krzysztof Koźmic to write a nice article about what sort of problem a DI Container solves. I agree with the article, but want to provide a different perspective here.

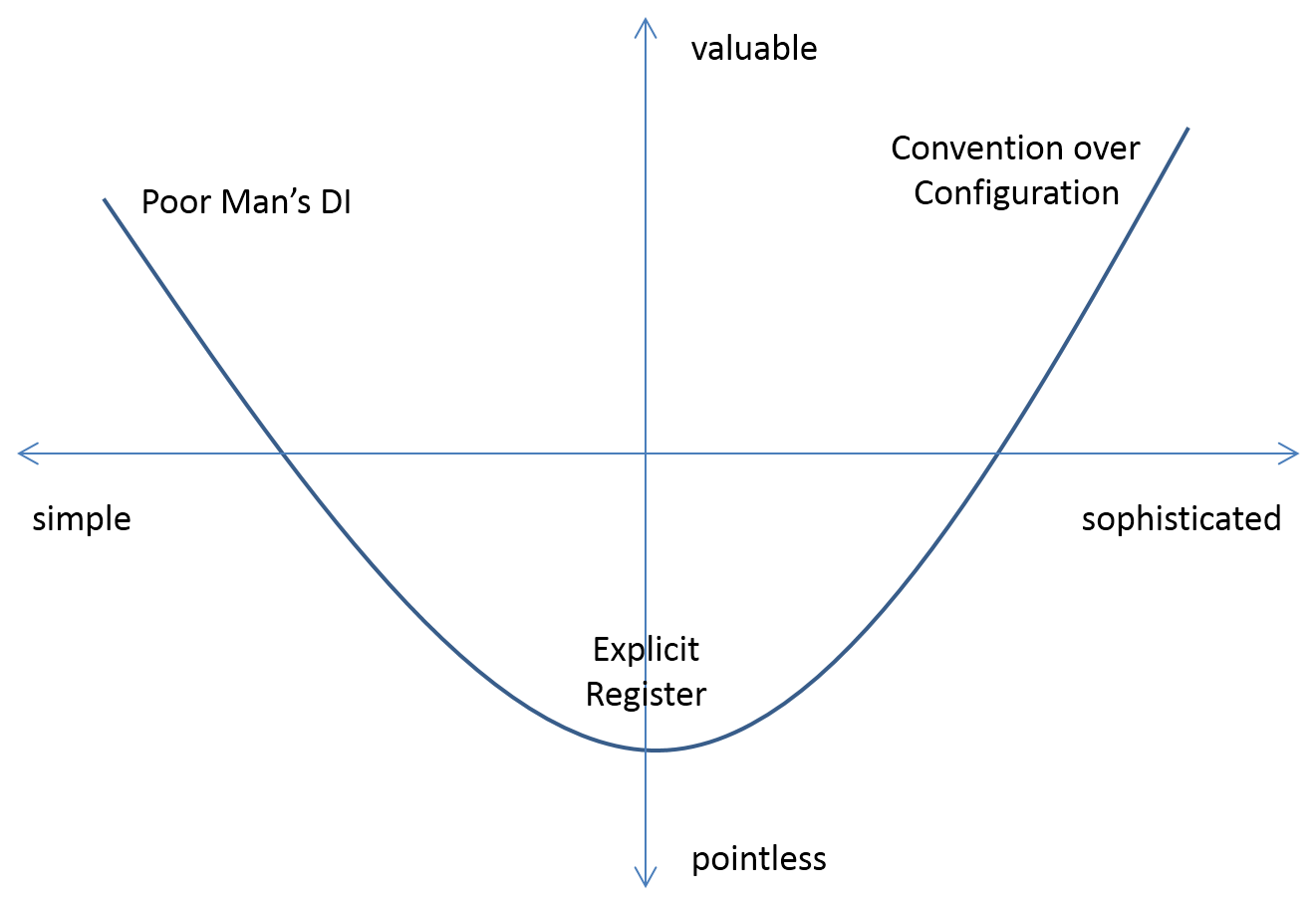

In short, it makes sense to me to illustrate the tradeoffs of Poor Man's DI versus DI Containers in a diagram like this:

The point of the diagram is that Poor Man's DI can be valuable because it's simple, while a DI Container can be either valuable or pointless depending on how it's used. However, when used in a sufficiently sophisticated way I consider a DI Container to offer the best value/cost ratio. When people criticize DI Containers as being pointless I suspect that what really happened was that they gave up before they were out of the Trough of Disillusionment. Had they continued to learn, they might have arrived at a new Plateau of Productivity.

DI style Advantages Disadvantages Poor Man's DI- Easy to learn

- Strongly typed

- High maintenance

- Weakly typed

- Low maintenance

- Hard to learn

- Weakly typed

There are other, less important advantages and disadvantages of each approach, but here I'm focusing on three main axes that I consider important:

- How easy is it to understand and learn?

- How soon will you get feedback if something is not right?

- How easy is it to maintain?

The major advantage of Poor Man's DI is that it's easy to learn. You don't have to learn the API of any DI Container (Unity, Autofac, Ninject, StructureMap, Castle Windsor, etc.) and while individual classes still use DI, once you find the Composition Root it'll be evident what's going on and how object graphs are constructed. No 'magic' is involved.

The second big advantage of Poor Man's DI is often overlooked: it's strongly typed. This is an advantage because it provides the fastest feedback about correctness that you can get. However, strong typing cuts both ways because it also means that every time you refactor a constructor, you will break the Composition Root. If you are sharing a library (Domain Model, Utility, Data Access component, etc.) between more than one application (unit of deployment), you may have more than one Composition Root to maintain. How much of a burden this is depends on how often you refactor constructors, but I've seen projects where this happens several times each day (keep in mind that constructor are implementation details).

If you use a DI Container, but explicitly Register each and every component using the container's API, you lose the rapid feedback from strong typing. On the other hand, the maintenance burden is also likely to drop because of Auto-wiring. Still, you'll need to register each new class or interface when you introduce them, and you (and your team) still has to learn the specific API of that container. In my opinion, you lose more advantages than you gain.

Ultimately, if you can wield a DI Container in a sufficiently sophisticated way, you can use it to define a set of conventions. These conventions define a rule set that your code should adhere to, and as long as you stick to those rules, things just work. The container drops to the background, and you rarely need to touch it. Yes, this is hard to learn, and is still weakly typed, but if done right, it enables you to focus on code that adds value instead of infrastructure. An additional advantage is that it creates a positive feedback mechanism forcing a team to produce code that is consistent with the conventions.

Example: Poor Man's DI #

The following example is part of my Booking sample application. It shows the state of the Ploeh.Samples.Booking.Daemon.Program class as it looks in the git tag total-complexity (git commit ID 64b7b670fff9560d8947dd133ae54779d867a451).

var queueDirectory =

new DirectoryInfo(@"..\..\..\BookingWebUI\Queue").CreateIfAbsent();

var singleSourceOfTruthDirectory =

new DirectoryInfo(@"..\..\..\BookingWebUI\SSoT").CreateIfAbsent();

var viewStoreDirectory =

new DirectoryInfo(@"..\..\..\BookingWebUI\ViewStore").CreateIfAbsent();

var extension = "txt";

var fileDateStore = new FileDateStore(

singleSourceOfTruthDirectory,

extension);

var quickenings = new IQuickening[]

{

new RequestReservationCommand.Quickening(),

new ReservationAcceptedEvent.Quickening(),

new ReservationRejectedEvent.Quickening(),

new CapacityReservedEvent.Quickening(),

new SoldOutEvent.Quickening()

};

var disposable = new CompositeDisposable();

var messageDispatcher = new Subject<object>();

disposable.Add(

messageDispatcher.Subscribe(

new Dispatcher<RequestReservationCommand>(

new CapacityGate(

new JsonCapacityRepository(

fileDateStore,

fileDateStore,

quickenings),

new JsonChannel<ReservationAcceptedEvent>(

new FileQueueWriter<ReservationAcceptedEvent>(

queueDirectory,

extension)),

new JsonChannel<ReservationRejectedEvent>(

new FileQueueWriter<ReservationRejectedEvent>(

queueDirectory,

extension)),

new JsonChannel<SoldOutEvent>(

new FileQueueWriter<SoldOutEvent>(

queueDirectory,

extension))))));

disposable.Add(

messageDispatcher.Subscribe(

new Dispatcher<SoldOutEvent>(

new MonthViewUpdater(

new FileMonthViewStore(

viewStoreDirectory,

extension)))));

var q = new QueueConsumer(

new FileQueue(

queueDirectory,

extension),

new JsonStreamObserver(

quickenings,

messageDispatcher));

RunUntilStopped(q);

Yes, that's a lot of code. I deliberately chose a non-trivial example to highlight just how much stuff there might be. You don't have to read and understand all of this code to appreciate that it might require a bit of maintenance. It's a big object graph, with some shared subgraphs, and since it uses the new keyword to create all the objects, every time you change a constructor signature, you'll need to update this code, because it's not going to compile until you do.

Still, there's no 'magical' tool (read: DI Container) involved, so it's pretty easy to understand what's going on here. As Dan North put it once I saw him endorse this technique: 'new' is the new 'new' :) Once you see how Explicit Register looks, you may appreciate why.

Example: Explicit Register #

The following example performs exactly the same work as the previous example, but now in a state (git tag: controllers-by-convention; commit ID: 13fc576b729cdddd5ec53f1db907ec0a7d00836b) where it's being wired by Castle Windsor. The name of this class is DaemonWindsorInstaller, and all components are explictly registered. Hang on to something.

container.Register(Component

.For<DirectoryInfo>()

.UsingFactoryMethod(() =>

new DirectoryInfo(@"..\..\..\BookingWebUI\Queue").CreateIfAbsent())

.Named("queueDirectory"));

container.Register(Component

.For<DirectoryInfo>()

.UsingFactoryMethod(() =>

new DirectoryInfo(@"..\..\..\BookingWebUI\SSoT").CreateIfAbsent())

.Named("ssotDirectory"));

container.Register(Component

.For<DirectoryInfo>()

.UsingFactoryMethod(() =>

new DirectoryInfo(@"..\..\..\BookingWebUI\ViewStore").CreateIfAbsent())

.Named("viewStoreDirectory"));

container.Register(Component

.For<IQueue>()

.ImplementedBy<FileQueue>()

.DependsOn(

Dependency.OnComponent("directory", "queueDirectory"),

Dependency.OnValue("extension", "txt")));

container.Register(Component

.For<IStoreWriter<DateTime>, IStoreReader<DateTime>>()

.ImplementedBy<FileDateStore>()

.DependsOn(

Dependency.OnComponent("directory", "ssotDirectory"),

Dependency.OnValue("extension", "txt")));

container.Register(Component

.For<IStoreWriter<ReservationAcceptedEvent>>()

.ImplementedBy<FileQueueWriter<ReservationAcceptedEvent>>()

.DependsOn(

Dependency.OnComponent("directory", "queueDirectory"),

Dependency.OnValue("extension", "txt")));

container.Register(Component

.For<IStoreWriter<ReservationRejectedEvent>>()

.ImplementedBy<FileQueueWriter<ReservationRejectedEvent>>()

.DependsOn(

Dependency.OnComponent("directory", "queueDirectory"),

Dependency.OnValue("extension", "txt")));

container.Register(Component

.For<IStoreWriter<SoldOutEvent>>()

.ImplementedBy<FileQueueWriter<SoldOutEvent>>()

.DependsOn(

Dependency.OnComponent("directory", "queueDirectory"),

Dependency.OnValue("extension", "txt")));

container.Register(Component

.For<IChannel<ReservationAcceptedEvent>>()

.ImplementedBy<JsonChannel<ReservationAcceptedEvent>>());

container.Register(Component

.For<IChannel<ReservationRejectedEvent>>()

.ImplementedBy<JsonChannel<ReservationRejectedEvent>>());

container.Register(Component

.For<IChannel<SoldOutEvent>>()

.ImplementedBy<JsonChannel<SoldOutEvent>>());

container.Register(Component

.For<ICapacityRepository>()

.ImplementedBy<JsonCapacityRepository>());

container.Register(Component

.For<IConsumer<RequestReservationCommand>>()

.ImplementedBy<CapacityGate>());

container.Register(Component

.For<IConsumer<SoldOutEvent>>()

.ImplementedBy<MonthViewUpdater>());

container.Register(Component

.For<Dispatcher<RequestReservationCommand>>());

container.Register(Component

.For<Dispatcher<SoldOutEvent>>());

container.Register(Component

.For<IObserver<Stream>>()

.ImplementedBy<JsonStreamObserver>());

container.Register(Component

.For<IObserver<DateTime>>()

.ImplementedBy<FileMonthViewStore>()

.DependsOn(

Dependency.OnComponent("directory", "viewStoreDirectory"),

Dependency.OnValue("extension", "txt")));

container.Register(Component

.For<IObserver<object>>()

.UsingFactoryMethod(k =>

{

var messageDispatcher = new Subject<object>();

messageDispatcher.Subscribe(k.Resolve<Dispatcher<RequestReservationCommand>>());

messageDispatcher.Subscribe(k.Resolve<Dispatcher<SoldOutEvent>>());

return messageDispatcher;

}));

container.Register(Component

.For<IQuickening>()

.ImplementedBy<RequestReservationCommand.Quickening>());

container.Register(Component

.For<IQuickening>()

.ImplementedBy<ReservationAcceptedEvent.Quickening>());

container.Register(Component

.For<IQuickening>()

.ImplementedBy<ReservationRejectedEvent.Quickening>());

container.Register(Component

.For<IQuickening>()

.ImplementedBy<CapacityReservedEvent.Quickening>());

container.Register(Component

.For<IQuickening>()

.ImplementedBy<SoldOutEvent.Quickening>());

container.Register(Component

.For<QueueConsumer>());

container.Kernel.Resolver.AddSubResolver(new CollectionResolver(container.Kernel));

This is actually more verbose than before - almost double the size of the Poor Man's DI example. To add spite to injury, this is no longer strongly typed in the sense that you'll no longer get any compiler errors if you change something, but a change to your classes can easily lead to a runtime exception, since something may not be correctly configured.

This example uses the Registration API of Castle Windsor, but imagine the horror if you were to use XML configuration instead.

Other DI Containers have similar Registration APIs (apart from those that only support XML), so this problem isn't isolated to Castle Windsor only. It's inherent in the Explicit Register style.

I can't claim to be an expert in Java, but all I've ever heard and seen of DI Containers in Java (Spring, Guice, Pico), they don't seem to have Registration APIs much more sophisticated than that. In fact, many of them still seem to be heavily focused on XML Registration. If that's the case, it's no wonder many software thought leaders (like Dan North with his 'new' is the new 'new' line) dismiss DI Containers as being essentially pointless. If there weren't a more sophisticated option, I would tend to agree.

Example: Convention over Configuration #

This is still the same example as before, but now in a state (git tag: services-by-convention-in-daemon; git commit ID: 0a7e6f246cacdbefc8f6933fc84b024774d02038) where almost the entire configuration is done by convention.

container.AddFacility<ConsumerConvention>();

container.Register(Component

.For<IObserver<object>>()

.ImplementedBy<CompositeObserver<object>>());

container.Register(Classes

.FromAssemblyInDirectory(new AssemblyFilter(".").FilterByName(an => an.Name.StartsWith("Ploeh.Samples.Booking")))

.Where(t => !(t.IsGenericType && t.GetGenericTypeDefinition() == typeof(Dispatcher<>)))

.WithServiceAllInterfaces());

container.Kernel.Resolver.AddSubResolver(new ExtensionConvention());

container.Kernel.Resolver.AddSubResolver(new DirectoryConvention(container.Kernel));

container.Kernel.Resolver.AddSubResolver(new CollectionResolver(container.Kernel));

#region Manual configuration that requires maintenance

container.Register(Component

.For<DirectoryInfo>()

.UsingFactoryMethod(() =>

new DirectoryInfo(@"..\..\..\BookingWebUI\Queue").CreateIfAbsent())

.Named("queueDirectory"));

container.Register(Component

.For<DirectoryInfo>()

.UsingFactoryMethod(() =>

new DirectoryInfo(@"..\..\..\BookingWebUI\SSoT").CreateIfAbsent())

.Named("ssotDirectory"));

container.Register(Component

.For<DirectoryInfo>()

.UsingFactoryMethod(() =>

new DirectoryInfo(@"..\..\..\BookingWebUI\ViewStore").CreateIfAbsent())

.Named("viewStoreDirectory"));

#endregion

It's pretty clear that this is a lot less verbose - and then I even left three explicit Register statements as a deliberate decision. Just because you decide to use Convention over Configuration doesn't mean that you have to stick to this principle 100 %.

Compared to the previous example, this requires a lot less maintenance. While you are working with this code base, most of the time you can concentrate on adding new functionality to the software, and the conventions are just going to pick up your changes and new classes and interfaces. Personally, this is where I find the best tradeoff between the value provided by a DI Container versus the cost of figuring out how to implement the conventions. You should also keep in mind that once you've learned to use a particular DI Container like this, the cost goes down.

Summary #

Using a DI Container to compose object graphs by convention presents an unparalled opportunity to push infrastructure code to the background. However, if you're not prepared to go all the way, Poor Man's DI may actually be a better option. Don't use a DI Container just to use one. Understand the value and cost associated with it, and always keep in mind that Poor Man's DI is a valid alternative.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK