AoAD2 Practice: Team Dynamics

source link: https://www.jamesshore.com/v2/books/aoad2/team_dynamics

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

AoAD2 Practice: Team Dynamics

June 11, 2021

This is a pre-release excerpt of The Art of Agile Development, Second Edition, to be published by O’Reilly in 2021. Visit the Second Edition home page for information about the open development process, additional excerpts, and more.

Your feedback is appreciated! To share your thoughts, join the AoAD2 open review mailing list.

This excerpt is copyright 2007, 2020, 2021 by James Shore and Shane Warden. Although you are welcome to share this link, do not distribute or republish the content without James Shore’s express written permission.

Team Dynamics

Audience Whole TeamXXX by Diana Larsen

We steadily improve our ability to work together.

Your team’s ability to work together forms the bedrock of their ability to develop and deliver software. You need collaboration skills, the ability to share leadership roles, and an understanding of how teams evolve over time. Together, these skills determine your team dynamics.

Team dynamics are the invisible undercurrents that determine your team’s culture. They’re the way people interact and cooperate. Healthy team dynamics lead to a culture of achievement and well-being. Unhealthy team dynamics lead to a culture of disappointment and dysfunction.

What Makes a Team?

A team is more than a group of people. In their classic book, The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization, Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith describe six characteristics that differentiate teams from other groups:

[A real team] is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable. [Katzenbach and Smith 2015] (ch. 5, emphasis mine)

The Wisdom of Teams

Arlo Belshee suggests one further condition: a shared history. A group of people gain a sense of themselves as a team by spending time working together.

Allies Whole Team Purpose Alignment Task Planning Capacity Slack Stand-Up MeetingsIf you’ve followed the practices in this book, you have all the preconditions necessary to create a great team. You’ve formed a whole team, which is a small group of people with complementary skills. You’ve committed to a common purpose, which includes performance goals in the form of mission tests. You aligned on a common approach. And you’ve taken ownership of the work and hold each other accountable, using practices such as task planning, capacity, slack, and stand-up meetings.

Now you need to develop your ability to work together.

Team Development

In 1965, Bruce W. Tuckman created a well-known model of group development. [Tuckman 1965] In it, he described four—and later, five—stages of group development: forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning. His model outlines shifts in familiarity and interactions over time.

Don’t interpret the Tuckman model as an inevitable, purely linear progression.

No model is perfect. Don’t interpret the Tuckman model as an inevitable, purely linear progression. Teams can exhibit behaviors from any of the first four stages. Changes in membership, such as gaining members or losing valued teammates may cause a team to slip into an earlier stage. When experiencing changes in environment, such as a move from colocated to remote work, or vice versa, a teams may regress from later stages to earlier ones. Nevertheless, Tuckman’s model offers useful clues. You can use it to perceive patterns of behavior in your team, and to decide how to best support each other.

Forming: The new kid in class

The team forms and begins working together. Individual team members recognize a sensation not unlike being the new kid in class: They’re not committed to working with others, but they want to feel included—or rather, not excluded—by the rest of the group. Team members are busy gaining the information they need to feel oriented and safe in their new territory.

You’re likely to see responses such as:

Excitement, anticipation, and optimism.

Pride in individual skills.

Concern about imposter syndrome (fear of being exposed as unqualified).

An initial, tentative attachment to the team.

Suspicion and anxiety about the expected team effort.

While forming, the team may produce little, if anything, that concerns its task goals. This is normal. The good news is that, with support, most teams can move through this phase relatively quickly.

Allies Purpose Context AlignmentSupport the team with leadership and clear direction. Start out by giving team members a way to get acquainted with the work and each other. Establish a shared sense of the team’s combined strengths and personalities. Purpose, context, and alignment chartering are excellent ways to do so. You may benefit from other exercises to get to know each other, such as “A Connection-Building Exercise” on p.XX and “A Team Formation Activity” on p.XX.

Along with chartering, give people time to discuss and develop their plan. Focus on the “do-able;” getting things done will build a sense of early success. (“Your First Week” on p.XX describes how to get started.) Make sure people are aware of resources available to the team, such as information, training, and support.

Acknowledge feeling of newness, ambivalence, confusion, or annoyance. They are natural at this stage. Although the chartering sessions should have helped make team responsibilities clear, clarify any remaining questions about work expectations, boundaries of authority and responsibility, and working agreements. Make sure people know how their team fits with other teams working on the same product. For in-person teams, explain what nearby teams are working on, even if it isn’t related to the team’s work.

During the Forming stage, team members need the following skills:

Peer-to-peer communication and feedback

Group problem-solving

Interpersonal conflict management

Ensure the team has coaching, mentoring, or training in these skills as needed.

A Team Formation Activity

Use this discussion to help your team form. It’s also useful if you need a reset after a disruption. It’s a simple group discussion:

Thinking back on your experiences as part of a team (any kind of team, including a sports team, church group, band, or choir), when were you most effective as a team member? Tell us a short story about that time. What workplace conditions fostered effective teamwork?

Reflect on the times and situations in your life when you have collaborated on a team. What do you notice about yourself, or your contribution, that you value? What do you value most about those teams?

What do you consider to be the core factor that creates, nurtures, and sustains effective teams in organizations? What is the core factor that creates, nurtures, and sustains effective teamwork? Is there any difference?

What three wishes would you make to cause your experience on this team to be most worthwhile?

Storming: Group adolescence

The team begins its shift from a collection of individuals to a team. Though they aren’t yet fully effective, they have the beginnings of mutual understanding.

During the Storming stage, the team deals with disagreeable issues. It's a time of turbulence, colaboratively choosing direction and making decisions together. That's why Tuckman et al. called it “Storming.” Team members have achieved a degree of comfort—enough to begin challenging each others’ ideas. They understand each other well enough to know where areas of disagreement surface, and they willingly air differences of opinion. This dynamic can lead to creative tension, or destructive conflicts, depending on how it’s handled.

Expect the following behaviors:

Reluctance to get on with tasks, or many differing opinions about how to do so.

Wariness about continuous improvement approaches.

Sharp fluctuations in attitude about the team and its chances of success.

Frustration with lack of progress or other team members.

Arguments between team members, even when they agree on the underlying issue.

Questioning the wisdom of the people who selected the team structure.

Suspicion about the motives of the people who appointed other members to the team. (These suspicions may be specific or generalized, and are often based more on past experience than the current situation.)

Support a Storming team by keeping an eye out for disruptive actions, such as defensiveness, competition between team members, factions or choosing sides, and jealousy. Expect increased tension and stress.

Ally SafetyAs you see these behaviors, be ready to intervene by describing the patterns you see. For example, “I notice that there’s been a lot of conflict around design approaches, and people are starting to form sides. Is there a way to bring it back to a more collegial discussion?” Maintain transparency, candor, and feedback, and surface typical conflict issues. Openly discuss the role of conflict and pressure in creative problem solving, including the connection between psychological safety and healthy conflict. Celebrate small team achievements.

When you notice an accumulation of storming behaviors on the team, typically a few weeks after the team first forms, bring the team together for a discussion of trust:

Think back on all your experiences as part of a team (any kind of team). When did you have the most trust in your teammates? Tell us a short story about that time. What workplace conditions allowed trust to build?

Reflect on the times and situations in your life when you have been trustworthy. What do you notice about yourself that you value? How have you built trust with others?

In your opinion, what is the core factor that creates and sustains trust in organizations? What is the core factor that creates, nurtures, and sustains trust among team members?

What three wishes would you make to heighten trust and healthy communication in this team?

This is a difficult stage, but it will help team members gain wisdom and lay the groundwork for the next stage. Watch for a sense of growing group cohesion. As cohesion grows, ensure that each member continues to express their diverse opinions, rather than shutting it down in favor of false harmony. (See “Dont Shy Away From Conflict” on p.XX.)

Norming: We’re #1

Team members have bonded together as a cohesive group. They’ve found a comfortable working cadence and enjoy their collaboration. They identify as part of the team. In fact, they may identify so closely, and enjoy working together so much, symbols of belonging appear in the workspace. You might notice matching or very similar t-shirts, coffee cups with the team name, or coordinated laptop stickers. Remote teams might have "wear-a-hat" or "Hawaiian shirt" days.

Norming teams have created agreement on structure and working relationships. Informal, implicit behavior norms that supplement the team’s working agreements develop through their collaboration. People outside the team may notice and comment on the team’s “teamliness.” Some may envy it—particularly if team members begin to flaunt their successes or declare their team “the best.”

Their pride is warranted. Teams in the Norming stage make significant, regular progress toward their goals. Team members face risks together and work well together. You’ll see the following behaviors:

A new ability to express criticism constructively.

Acceptance and appreciation of differences among team members.

Relief that this just might all work out well.

More friendliness.

More sharing of personal stories and confidences.

Open discussions of team dynamics.

Desire to review and update working agreements and boundary issues with other teams.

How do you support a Norming team? Help the team look outside their own team boundaries and broaden their focus. Facilitate contact with customers and suppliers. (Field trips!) If their work relates to the work of other teams, arrange for them to train in cross-team groups.

Support their cohesiveness and open their horizons, as well. Look for opportunities for team members to share experiences, such as volunteering together or presenting to other parts of the organization. Make sure these opportunities are suitable for all team members, so your good intentions don’t create in- and out-groups.

The skills needed by Norming teams include:

Feedback and listening.

Group decision-making processes.

Understanding the organizational perspective on their work.

Books such as What Did You Say? The Art of Giving and Receiving Feedback [Seashore et al. 2013] and Facilitators’ Guide to Participatory Decision-Making [Kaner 1998] will help the team learn the first two skills, and including the whole team in discussions with organizational leaders will help with the third.

Watch out for attempts to preserve harmony by avoiding conflicts.

Watch out for attempts to preserve harmony by avoiding conflicts. In their reluctance to return to Storming, team members may display groupthink: a form of false harmony where team members avoid disagreeing with each other, even when it’s justified. Groupthink: Psychological Studies of Policy Decisions and Fiascoes [Janis 1982] is a classic book that explores this phenomenon.

Ally SafetyDiscuss team decision-making approaches when you see the symptoms of groupthink. One sign is team members holding back on critical remarks to keep the peace, especially if they bring up their critiques later, after it’s too late to change course. Ask for critiques, and make sure team members feel safe to disagree.

One way to avoid groupthink is start discussions by defining the desired outcome. Work toward an outcome rather than away from a problem. Experiment with the following ground rules for team decisions:

Agree that each team member will act as a critical evaluator.

Promote open inquiry rather than stating positions.

Adopt a decision process that includes identifying at least three viable options before a choice is made.

Appoint a “contrarian” to search for counter-examples.

Split the team into small groups for independent discussion.

Schedule a “second chance” meeting to review the decision.

Performing: Team synergy

The team’s focus has shifted to getting the job done. Performance and productivity are the order of the day. The team connects with their part in the mission of the larger organization. They follow familiar, established procedures for making decisions, solving problems, and maintaining a collaborative work climate. Now the team is getting a lot of work done.

“Performing” teams transcend expectations. They exhibit greater autonomy, reach higher achievements, and have developed the ability to make rapid, high-quality decisions. Team members achieve more together than anyone would have expected from the sum of their individual effort. Team members continue to show loyalty and commitment to each other, while expressing less emotion about interactions and tasks than in earlier stages.

You’ll see these behaviors:

Significant insights into personal and team processes.

Little need for facilitative coaching. Such coaches will spend more time on liaising and mediating with the broader organization than on internal team needs.

Collaboration that’s understanding of team members’ strengths and limits.

Remarks such as “I look forward to working with this team,” “I can’t wait to come to work,” “This is my best job ever,” and “How can we reach even greater success?”

Confidence in each other, and trust that each team member will do their part toward accomplishing team goals.

Preventing, or working through, problems and destructive conflicts.

Individuals who have worked on Performing teams always remember their experience. They have stories about feeling closely attached to their teammates. If the team spends much time in Performing, team members may be very emotional about potential team termination or rearrangement.

Although Performing teams are at the pinnacle of team development, they still need to learn to work well with people outside the team. They’re not immune to reverting to earlier stages, either. Changes in team membership can disrupt their equilibrium, as can significant organizational change and disruptions to their established work habits. And there are always opportunities for further improvement. Keep learning, growing, and improving.

Adjourning: Separating and moving on

The team inevitably separates. They achieve their final purpose, or team members decide it’s time to move on.

Effective, highly productive teams acknowledge this stage. They recognize the benefit of farewell “ceremonies” that celebrate the team’s time together and help team members move on to their next challenge.

Postpone Adjourning as long as possible.

Teams’ growth depends on the length of time the members stay together. Help teams reach their maximum effectiveness by postponing Adjourning as long as possible. Rather than reforming the team for every piece of work, assign work to existing teams.

Every team Adjourns eventually, though, and team members who have worked in effective, healthy teams keep the skills they learned as part of that team. If their organization allows it, they can establish new, healthy team dynamics in their next team assignment. Heidi Helfand’s approach, Dynamic Reteaming, [Helfand 2020] relies on building this competence.

Communication, Collaboration, and Interaction

Team members’ communication, interaction, and collaboration creates group cohesion. These exchanges influence the team’s ability to work effectively—or not.

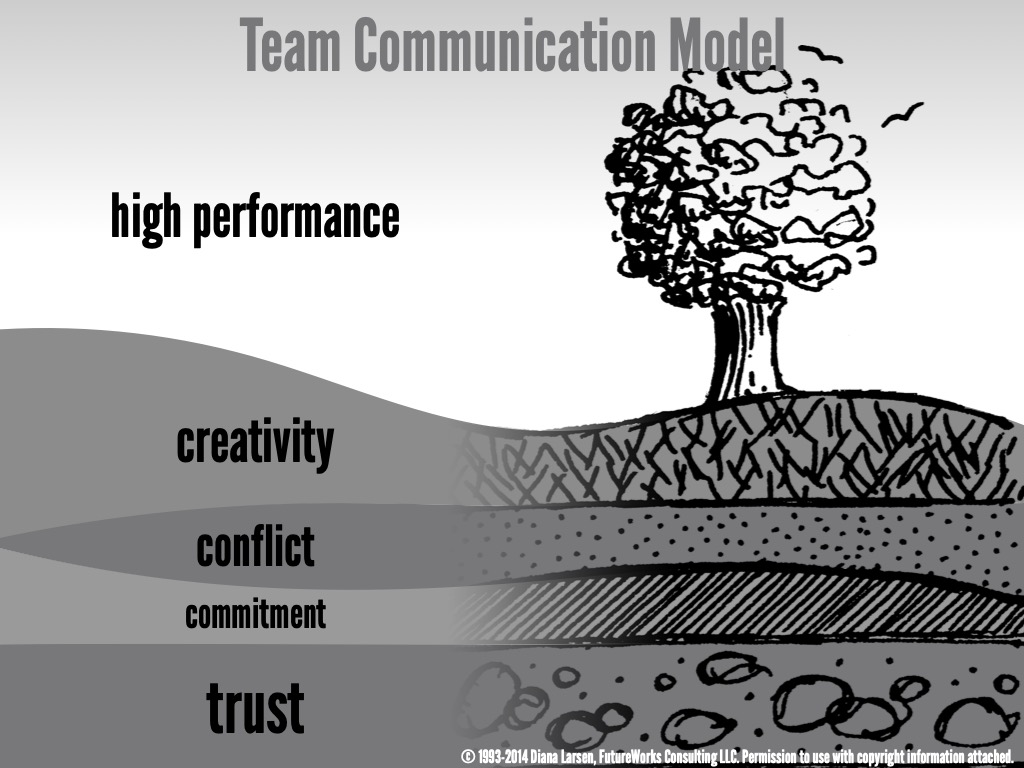

Consider my (Diana) Team Communication Model, shown in figure “Larsen’s Team Communication Model”, which shows how effective team communication requires developing an interconnected, interdependent series of communication skills. It starts with developing just enough trust to get started. Each new skill pulls the team upward, while strengthening the supporting skills below.

Figure 1. Larsen’s Team Communication Model

Start with a strong base of trust

Ally Alignment SafetyAs your teams form, concentrate on helping teams find trust in one another. It doesn’t need to be a deep trust; just enough to agree to work together and commit to the work. Getting to know one another helps. Use activities such as alignment chartering, “A Connection-Building Exercise” on p.XX, or “A Team Formation Activity” on p.XX.

The following six communication skills will help team members build trust:

Credibility: Act with consistency and reliably follow through.

Tune in: Show others you listened.

Self-disclose: Lift your “mask” (even a little bit helps; see “Allow Yourself to Be Vulnerable” on p.XX).

Empathy: Imagine yourself in the other person’s situation, from their perspective (see “Use Empathy” on p.XX).

Stretch: Express interest in your team and teammates (see “Be Curious” on p.XX).

Communicate: Seek and give effective feedback (see “Learn How to Give and Receive Feedback” on p.XX).

Support trust with three-fold commitment

Ally Purpose Alignment SafetyFrom a foundation of trust, your team will begin exploring the three-fold nature of team commitment:

Commitment to the team’s purpose;

Commitment to each other’s well-being; and

Commitment to the well-being of the team as a whole.

Chartering purpose and alignment will help build commitment. As commitment solidifies, trust will continue to grow. People’s sense of psychological safety will grow along with it.

Once commitment and trust start improving psychological safety, it’s a good time to examine the power dynamics of the team. No matter how egalitarian your team may be, power dynamics always exist. They’re part of being human. Left unaddressed or hidden, power dynamics turn destructive. It’s best to keep them out in the open, so the team can attempt to level the field.

Power dynamics come from individual perceptions of each other’s influence, ability to make things happen, and preferential treatment. Bring them into the open by holding a discussion of the power dynamics that exist in the team, and how they affect collaboration. Discuss how the team’s collective and diverse powers can be used to help the whole team.

Right-size conflicts with feedback

The more team members recognize each other’s commitment, the more their approach to conflict adapts. Rather than “you against me,” they start approaching conflicts as “us against the problem.” Focus on developing team members’ ability to give and receive feedback, as described in “Learn How to Give and Receive Feedback” on p.XX. Approach feedback with the following goals:

The feedback we give and get is constructive and helpful.

Our feedback is caring and respectful.

Feedback is an integral part of our work.

No one is suprised by feedback; we wait for explicit agreement before giving feedback.

We offer feedback to encourage behavior as well as to discourage or change behavior.

Peer-to-peer feedback helps to deal with interpersonal conflicts while they’re small. Unaddressed, molehill resentments have the potential to grow into mountains of mistrust. The skills team members develop for feedback within the team will help them in larger conflicts with forces outside the team.

Spark creativity and innovation

What is team innovation, but the clash of ideas that sparks new potential? Retaining healthy working relationships while the sparks fly is a team skill. It rises from the ability to engage and redirect conflicts toward desired outcomes. It stimulates greater innovation and creativity. Team problem solving capability soars.

Allies Slack RetrospectivesDevelop team creativity by offering learning challenges and playful approaches. Build it in to the team’s routine. Use slack to explore new technologies, as described in “Dedicate Time to Exploration and Experimentation” on p.XX. Use retrospectives to experiment with new ideas. Make space for whimsy and inventive irrelevance. (Teach each other to juggle!)

Sustain high performance

When collaboration and communication skills join with task-focused skills, high performance becomes routine. The challenge lies in sustaining high performance. Avoid complacency. As a team, continue to refine your skills in building trust, committing to the work and each other, providing feedback, and sparking creativity. Look for opportunities to build resilience and further improve.

Shared Leadership

Mary Parker Follett, a management expert also known as “the mother of modern management,” was a pioneer in the fields of organizational theory and behavior. In discussing the role of leadership, she wrote:

Ally Whole TeamIt seems to me that whereas power usually means power-over, the power of some person or group over some other person or group, it is possible to develop the conception of power-with, a jointly developed power, a co-active, not a coercive power... Leader and followers are both following the invisible leader—the common purpose. [Graham 1995] (pp. 103, 172)

Mary Parker Follett

Effective Agile teams develop “power with” among all team members. They share leadership. (See “Key Idea: Self-Organizing Teams” on p.XX.) By doing so, they make the most of their collaboration and the skills of the whole team.

Mary P. Follett described “the law of the situation,” in which she argued for following the lead of the person with the most knowledge of the situation at hand. This is exactly how Agile teams are meant to function. It means that every team member has the potential to step into a leadership role. Everyone leads, at times, and follows a peer leader at others.

Team members can play a variety of leadership roles, as summarized in table “Leadership Roles”.1 People can play multiple roles, including switching at will, and multiple people can fill the same role. The important thing is coverage. Teams need all these kinds of leadership from their team members.

1These roles were developed by Diana Larsen and Esther Derby, based on [Benne and Sheats 1948]. XXX Double-check rendering of table with final stylesheet.

Table 1. Leadership Roles

Task-OrientedCollaboration-OrientedDirectionPioneer, InstructorInfluencer, FollowerGuidanceCommentator, CoordinatorPromoter, PeacemakerEvaluationCritic, Gatekeeper, ContrarianReviewer, MonitorPioneers (task-oriented direction) ask questions and seek data. They scout what’s coming next, looking for new approaches and bringing fresh ideas to the team.

Instructors (task-oriented direction) answer questions, supply data, and coach others in task-related skills. They connect the team to relevant sources of information.

Influencers (collaboration-oriented direction) encourage the team in chartering, initiating working agreements, and other activities that build awareness of team culture.

Followers (collaboration-oriented direction) provide support and encouragement. They step back, allowing others to take the lead in their areas of strength, or where they’re developing strength. They conform to team working agreements.

Commentators (task-oriented guidance) explain and analyze data. They put information into context.

Coordinators (task-oriented guidance) pull threads of work together in a way that make sense. They link and integrate data and align team activities onto their tasks.

Promoters (collaboration-oriented guidance) focus on equitable team member participation. They ensure every team member has the chance to participate and help. They encourage quieter team members to contribute their perspectives on issues that affect the team.

Peacemakers (collaboration-oriented guidance) work for common ground. They seek harmony, consensus, and compromise when needed. They may mediate disputes that team members have difficulty solving on their own.

Critics (task-oriented evaluation) evaluate and analyze relevant data, looking for risks and weaknesses in the team’s approach.

Gatekeepers (task-oriented evaluation) encourage work discipline and maintain working agreements, as well as managing team boundaries to keep interference at bay.

Contrarians (task-oriented evaluation) protect the team from groupthink by deliberately seeking alternative views and opposing habitual thinking. They also vet the team’s decisions and against the team’s values and principles.

Reviewers (collaboration-oriented evaluation) ensure the team is meeting acceptance criteria and responding to customer needs.

Monitors (collaboration-oriented evaluation) attend to how the whole team is working together. (Are they working well, or not?) They protect the team’s psychological safety and foster healthy working relationships among team members.

“Follower” is a particularly powerful role for people who are expected to lead.

Although it may seem strange to include “follower” as a leadership role, actively following other people’s lead helps the team learn to share leadership responsibilities. It’s a particularly powerful role for people who are expected to lead, such as senior team members.

Teams that share leadership across these roles can be called leaderful teams. To develop a leaderful team, discuss these leadership roles together. A good time to do so is when you notice uneven team participation or over-reliance on a single person to make decisions. Share the list of roles and ask the following questions:

How many of the leadership roles does each team member naturally enact?

Is anyone overloaded with leadership roles? Or filling a role they don’t want?

Which of these roles need multiple people to fill? (For example, on Norming teams, the Contrarian role is best if rotated among several team members.)

Which of these roles are missing on our team? What's the impact of missing someone to fill these roles?

How might we fill the missing roles? Who wants practice in this aspect of leadership?

What else do we notice about these roles?

Focus the team on choosing how they will ensure their effective collaboration by covering the leadership roles. Be open to creating new working agreements in response to this conversation.

Some team members may be natural Contrarians, but if they always play that role, the rest of the team may fall into the trap of discounting their comments. “Oh, never mind. Li always sees the bleakest, most pessimistic side of things!” For the Contrarian role in particular, ensure that it’s shared among various team members, so it remains effective.

Toxic Behavior

Toxic behavior is any behavior that produces an unsafe environment, degrades team dynamics, or damages the team’s ability to achieve their purpose.

If a team member is exhibiting toxic behaviors, start by remembering the Retrospective Prime Directive: “Regardless of what we discover, we must understand and truly believe that everyone did the best job he or she could, given what was known at the time, his or her skills and abilities, the resources available, and the situation at hand.” [Kerth 2001] (ch. 1) Assume the person is doing the best job they can.

Look for environmental pressures first. For example, a team member may have a new baby and not be getting enough sleep. Or a new team member may be solely responsible for a vital subsystem they don't yet know well. Together, the team can seek systemic adjustments that help people improve their behavior. For example, agreeing to move the morning stand-up so the new parent can come in later, or sharing responsibility for the vital subsystem.

The next step is giving feedback to the person in question. Use the interpersonal feedback process described in “Learn How to Give and Receive Feedback” on p.XX to describe the impact of their behavior, and request a change. Very often, that’s enough. They didn’t realize how their behavior affected the team and they do better.

Be careful not to misidentify Contrarians as toxic.

Sometimes, teams can label colleagues as toxic when they aren’t actually doing anything wrong. This can easily happen to people who regularly take the Contrarian leadership role. They don’t go along with the rest of the team’s ideas, or they perceive a risk or obstacle that others miss, and won’t let it go. Be careful not to misidentify Contrarians as toxic. Teams need Contrarians to avoid groupthink. However, it may be worth having a discussion about rotating the role.

Ally SafetyIf a person really is showing toxic behavior, they may ignore the team’s feedback, or refuse to adjust to the team’s psychological safety needs. If that happens, they are no longer a good match for the team. Sometimes, it’s just a personality clash, and they’ll do well on another team.

At this point, it’s time to bring in your manager, or whoever assigns team membership. Explain the situation. Good managers understand how every team member’s performance depends on every other team member. An effective leader will step in to help the team. For them to do so, the team needs to inform them of what they need, as well as the steps they’ve already taken to encourage changes in behavior.

Some managers may resist removing a person from the team, especially if they identify the team member as a “star performer” or “hero.” They could suggest the team should accommodate the behavior instead. Unfortunately, this tends to damage the team’s performance as a whole. Ironically, it can make the “star performer” seem like even more of a star, as they push the people around them down.

In this situation, you can only decide for yourself whether the benefits from being part of the team are worth the toxic behavior you experience. If they’re not, your best option is to move to another team or organization.

Questions

Isn’t it important that a team have one leader—a “single, wringable neck?” How does that work with leaderful teams?

A “single, wringable neck” is a satisfying way to simplify a complex problem, but it’s not so satisfying for the person whose neck is being wrung. It’s also contrary to the Agile ideal of collective ownership (see “Key Idea: Collective Ownership” on p.XX). The team as a whole is responsible. There’s no scapegoat to take the fall when things go wrong, or reap the rewards when things go well, because success and failure is the result of a complex interaction between multiple participants and factors. Every team member’s contribution is vital.

This isn’t just abstract philosophy. Leaderful teams do better work, and develop into high-performing teams more quickly. Sharing leadership builds stronger teams.

Prerequisites

Allies Energized Work Whole Team Team Room ManagementFor these ideas to become reality, both your team and organization need to be on board. Team members need to be energized and motivated to do good—possibly great—work together. It won’t work if people are just interested in punching a clock and being told what to do. Similarly, your organization needs to invest in teamwork. This includes creating a whole team, a team room, and an Agile-friendly approach to management.

Indicators

When your team has healthy team dynamics:

Team members generally enjoy coming to work.

Team members say they can rely on their teammates to follow through on their commitments, or communicate when they can’t.

Team members trust that everyone on the team is committed to achieving the team’s purpose.

Team members know each other’s strengths and support each other’s limits.

Team members work well together and celebrate progress and successes.

Alternatives and Experiments

The material in this practice only represents a tiny portion of the valuable knowledge available about teams, team dynamics, managing conflicts, leadership, and many more topics that affect team effectiveness. The references throughout this practice and in the “Further Reading” section have a wealth of information. But even that only begins to scratch the surface. Ask a mentor for their favorites. Keep learning and experimenting: It’s a lifelong journey.

Further Reading

Keith Sawyer has spent his career exploring creativity, innovation, and improvisation, and their roots in effective collaborative effort. In Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration [Sawyer 2017], he offers insightful anecdotes as well as ideas for expanding the capability and capacity of teams focus on learning work such as software development.

Roger Nierenberg’s memoir and instruction guide for leaders, Maestro: A Surprising Story about Leading by Listening [Nierenberg 2009], contributes “out of the box” ways of thinking about leadership. He also has a website with videos that demonstrate his techniques at http://www.musicparadigm.com/videos/.

The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High Performance Organization [Katzenbach and Smith 2015] is the classic, foundational book about high-performing teams, their characteristics, and the environments that help them flourish. This book is constantly referred to in the Agile community and forms part of the “cultural literacy” of agility and teams.

Shared Leadership: Reframing the Hows and Whys of Leadership [Pearce and Conger 2002] is a compilation of the best ideas about leaderful teams and organizations. It’s an academic text, and can be a challenging read, but it’s well worth exploring to expand your ideas about who, and what, is a leader.

Crucial Accountability: Tools for Resolving Violated Expectations, Broken Commitments, and Bad Behavior [Patterson et al. 2013] is a follow-up to the excellent Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High [Patterson et al. 2011], which focused on techniques for resolving disagreements. In Crucial Accountability, the authors focus on resolving disappointments, which is fundamental to avoiding the insidious resentments and undermined work relationships that can poison interactions and erode hard-won team trust. In Appendix A, they offer a self-assessment for checking your own crucial accountability skills.

Share your feedback about this excerpt on the AoAD2 mailing list! Sign up here.

For more excerpts from the book, or to get a copy of the Early Release, see the Second Edition home page.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK