The 26 best new apps of 2020

source link: https://www.fastcompany.com/90587805/worst-covid-19-conspiracies-of-2020

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

- 12-21-20

TikTok has a year in review feature, too: Here’s how to get it

What was your TikTok vibe in 2020? Take a scroll down memory lane and find out.

If you really want to look back on this dumpster fire of a year, there’s one way that might bring a smile to your face. TikTok just released its “Year in TikTok” feature that promises to recap the metrics that kept you mesmerized for so many minutes (or hours or days) while you were pinned in by the pandemic.

If you’re a regular TikTok user (and there were 87 million added in the U.S. alone this June, according to Sensor Tower), you can find your recap in the “For You” section or on TikTok’s Discover page. You’ll be able to see highlights, such as how long you’ve been a user of the app, and metrics, such as the tracks you’ve played the most, creative effects you used, and likes and comments on your videos, among other data. TikTok is offering up a personalized “vibe” based on themes you gravitated toward the most.

For those newer to the app—or anyone curious about what’s most popular for the larger, global community— TikTok serves up its own “Top 100.” Here’s where you’ll find viral videos, trends, hashtags, challenges, creators, celebrities, song, snacks, and special effects designed to keep you scrolling, clicking, and discovering.

This year may have presented challenging circumstances worldwide, but TikTok generated its own diversions. Heck, even Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks got on board the TikTok train to one-up the cranberry-juice-swigging “Dreams Challenge,” capping one crazy year. If you’re curiosity is piqued and you don’t have the app, you can scroll through the Top 100 here.

About the author

Lydia Dishman is a reporter writing about the intersection of tech, leadership, and innovation. She is a regular contributor to Fast Company and has written for CBS Moneywatch, Fortune, The Guardian, Popular Science, and the New York Times, among others.

Featured Video

- 12-18-20

- connected world

Wearable gadgets could help catch COVID-19 before symptoms show

Early data suggests that continuous temperature monitoring could be more helpful than random fever checks.

Fever monitoring has developed something of a bad reputation under COVID-19. While having a fever is one of COVID-19’s telltale symptoms, temperature checks capture only a moment in time. Unless someone is stricken with fever, they tell us very little about a person’s state of health. But a new report suggests that body temperature can play a far more useful role in understanding health—we’re just using it wrong.

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, and the University of California, San Diego, have shown that constant temperature surveillance could be a promising method for detecting and predicting the onset of fever in COVID-19. In a 50-person feasibility study, researchers used the Oura Ring, a finger-worn sleep tracker, to monitor temperatures of participating healthcare workers and adult volunteers.

Everyone has a slightly different baseline body temperature. If that baseline starts to tick upward over a series of days, it may indicate illness. However, this study was not designed to definitively show that the Oura Ring—or any other temperature-tracking wearable—can predict COVID-19. This was merely a feasibility study, showing whether it’s possible to use this tech to conduct further studies into fever-related illness detection. Still, it represents a first step in understanding whether temperature monitoring can ultimately be used to detect or predict illness.

The study is part of an ongoing research project between UCSD and UCSF called TemPredict that hopes to understand the role body temperature, heart rate, and other physiological signals can play in predicting the occurrence of COVID-19 symptoms. The concept under investigation is whether data from wearables like the Oura Ring could be used to help public health officials navigate outbreaks like COVID-19 or even a regular flu season.

“For example, if you’re a public health official, you could have a weather map and just know a bunch of people are starting to get a fever in Seattle and [you] should go look at that,” says Benjamin Smarr, assistant professor of bioengineering and data Science at UCSD and lead author on the paper. “What this paper shows is that not only is that technically feasible, but that actually the physiology data seemed to do a much better job than the people of reporting when it is they seem like they are getting sick.”

A slow process

Tracking an outbreak like COVID-19 or any incident in public health can be slow moving, Smarr says. Public health officials have to wait until people are sick enough to go to a hospital or a doctor’s office and have their symptoms correlated to a particular disease. Then that data has to be reconciled with public health officials at the county level before a summary statistic is released.

“If people are willing to act as tracer particles, we could know within a day, if not in real time, where sickness events are happening,” Smarr says. Furthermore, he notes, public health officials could more quickly connect illness to either a specific disease outbreak or environmental effects such as weather, pollution, or accidents.

To use wearable-collected data would require a digital public health infrastructure that currently does not exist. The U.S healthcare system is frequently called a patchwork, but that would suggest that it’s in any way sewn together. In reality, each healthcare operator is its own carefully constructed garment. A person can amass a collection of different healthcare services, piecing them together much the way one does an outfit. This structure allows individuals to choose and shed services and systems based on what they think they need. This choice forces health systems to compete and, in theory, provide better care. In practice, it creates complications for public health efforts, as revealed by COVID-19.

While there is no public digital infrastructure currently that would allow for the kind of real-time health weather mapping that Smarr is envisioning, smart thermometer maker Kinsa has a program that gives a glimpse of what such a public health program could look like. The company works with schools that support students from low-income families to navigate flu season. Kinsa supplies families with smart thermometers and an app that records temperature data and symptoms and lets them text school nurses. School nurses get a platform where they can see anonymized temperature data for each grade. The system allows these schools and families to coordinate and reduce flu spread in schools.

Smarr says the difference between using a smart thermometer and a ring that constantly monitors body temperature is that a thermometer relies on an individual to experience symptoms and seek out a temperature measurement. It also captures only a single moment in time. The Oura Ring, by contrast, records broader and more nuanced temperature fluctuations over time, potentially giving public health authorities an ability to see an outbreak coming before it strikes.

The U.S. military is testing a version of this system. The Defense Innovation Unit, in collaboration with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, has paired a Garmin watch, the Oura Ring, and an analytics platform designed by Philips Healthcare to spot illness among troops before symptoms arrive. So far, it seems to be able to see illness coming two days beforehand. The program started with 400 participants in June but is expanding to 5,000, according to Defense One. Meanwhile, West Virginia University Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute is running a study that uses Oura to predict illness in healthcare workers.

To create a comparable system for the greater public, health officials would have to contend with privacy concerns. “I think there should absolutely be a public authority or even just a public record of the kind of physiological events that are happening,” Smarr says. “How you secure that and scrub individual information away from that is an interesting challenge.”

For now, using temperature as a beacon for public health status is merely in the research phase. Researchers at UCSF and UCSD have given the Oura Ring to 3,400 healthcare workers in various regions of the U.S., while Oura has enrolled more than 60,000 of its users. The results of the observational study are expected sometime next year.

About the author

Ruth Reader is a writer for Fast Company. She covers the intersection of health and technology.

- 12-18-20

- connected world

These virtual stores are a joyful twist on e-commerce

Online experiences that evoke the serendipity of traditional retail—complete with aisles of shelves—make shopping fun again. And they’re pandemic-safe, too.

The virtual store is back—and it’s the best retail experience we could have gotten during a COVID-19 lockdown.

Rather than resembling a printed catalog transformed into online form, as most e-commerce sites do, virtual stores use either 3D renderings of an environment or Google Street-View-like sequences of stitched-together photographic images of a physical location. They replicate neighborhood shopping, letting you walk through aisles and peruse items on display. They safely scratch the itch to be in a local store. But you don’t have to wear a mask, rush in and out, or worry about others not wearing masks or standing too close.

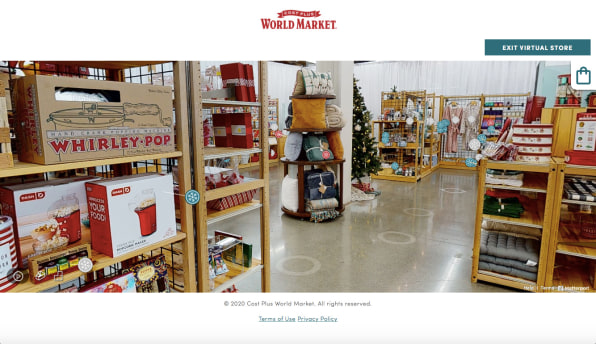

One example I visited for holiday shopping is Cost Plus World Market’s “World of Joy” virtual store, a pop-up online extension of the 243-store specialty import chain. Open only for the holidays this year, World of Joy allows customers to shop via a zoom-and-pan interface that works on PCs and mobile devices.

The fun of shopping at my local Cost Plus World Market comes in part from wandering about to see what’s new, and the serendipity of finding just the right item. I haven’t set foot in a shop for months, was in need of holiday gifts, and worked on one of the first virtual walk-through environments at Apple in the 1990s—so World of Joy checked all my boxes.

The experience is modeled on a neighborhood World Market store, with wooden shelves of goods and the same familiar visual merchandising as the chain’s mall outposts. However, the captured footage was not created in an actual store, but rather a space set up to look like one, set up in a larger area that is bounded by white curtains rather than walls. It looked like a cross between an exhibit at a trade show and a full-blown World Market.

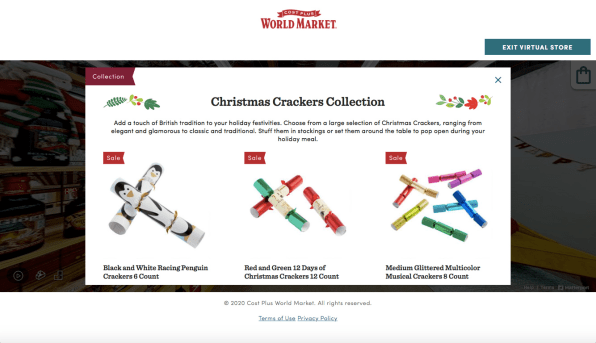

The controls are easy enough to manage, letting you click or tap your way around the store. Click on snowflake icons, and you can jump to shelf areas containing specific products or groupings. It’s easier to browse than to find specific items, as areas are not labeled and the “Floor Plan” option resembles a strange retail Advent calendar, with 50 sections that don’t indicate what they contain until you’ve clicked through to one. There’s also a “Dollhouse” mode, which offers a 3D rotatable view of the World of Joy with zones you can click.

Once you’ve selected a product, a more conventional website window opens on top of the shop with more information and the ability to place the item into a shopping bag. In general the World of Joy offers a smaller selection of merchandise such as games, clothing, kitchen items, and general holiday decor, and it is worth noting that it doesn’t sell alcohol, which is a staple of World Market’s offline stores.

Having been at home for such a long time, I loved roaming around, jumping to various shelves and seeing what was available. Each aisle had enough familiarity in its design language to make me want to look at the products. I even liked using the Advent-style floor plan to randomly pick sections of the store to visit.

Back to the future of online retail

The engine that drives World of Joy is from Matterport, a company that offers a 3D data platform that enables a space to be turned into an “accurate and immersive digital twin.” Matterport has also built virtual stores for Lily Pulitzer, Andersen Windows and Doors, Micha-Paris, Herman Miller, and others. Ferguson Bath, Kitchen, and Lighting Gallery, which has 250 showrooms across the U.S., has digitized 70 local showrooms using Matterport’s technology, with plans to add another 60.

These stores may be part of a new trend, but they also recall an earlier era. Even before the web, people were creating virtual walk-through environments. In the early 1990s, pan, zoom, and select interfaces were circulating in the technology community—some using video, and others based on rendered graphics. Dan O’Sullivan at NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program put his apartment online via a telephone interface that controlled prerecorded video on CD-ROM. “Dan’s Apartment ” gained a cult late-night cable TV following, and O’Sullivan interned at Apple around the same time that it was developing QuickTime, its multimedia framework.

In 1991, the same year that Apple released QuickTime, the company demoed The Virtual Museum, a 3D walk-through museum with exhibits on scientific topics that was released on CD-ROM in 1992. As an Apple employee at the time, I worked on this project, which allowed people to fly over the surface of Mars, see plants grow over time, and even to watch a galaxy unfold.

After the Virtual Museum’s release to museums and educational institutions worldwide, I spent some time investigating how it was used. One of the key findings was that people loved walking through the museum once, but after that, they wanted quick access to content. Fortunately, Apple provided a clickable floor plan; after a single walk-through, people used the map for reference.

As the web began to take off, some early commerce sites simulated traditional retail stores, complete with “shelves.” Some were built with Apple’s QuickTime VR, a method for transforming images into clickable pan-and-zoom panoramic environments. But with home bandwidth still an issue in the pre-broadband era, these walk-through environments didn’t become an enduring part of online retail. Instead, shopping evolved to emphasize grids, lists, still images, and carts, with the occasional video.

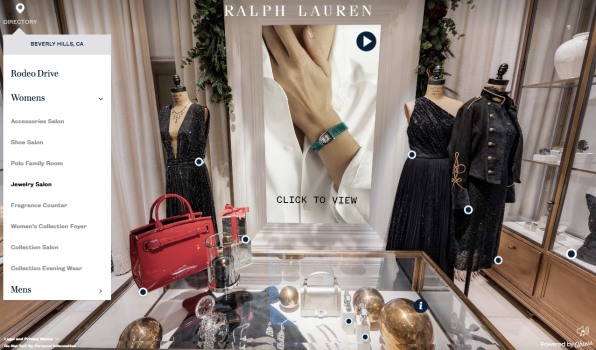

That is, until the coronavirus came along and we stopped being able to go into stores and embraced online shopping as our main mode for exploring the outside world. A recent Wall Street Journal noted that some retailers, such as Ralph Lauren, were reproducing exact replicas of offline locations in order to “stoke the fire” for future in-store visits once the pandemic has passed.

Ralph Lauren offers several faithful online walk-throughs of its stores; I dropped in on the Beverly Hills location, because I’ve been there and wanted to see how the digital version compared. A much more comprehensive experience than Cost Plus World Market’s World of Joy, it offers a side menu that lists departments, eliminating the need to “walk” through the space to get to a specific department. Unlike the silent World of Joy, it plays music, which adds to the experience. And because it’s an online recreation of an actual store—not just a temporary setup—there’s a richness and depth to the interior.

The Ralph Lauren store was created by Obsess, whose other retail clients include Tommy Hilfiger, Sam’s Club (with a National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation theme), and Charlotte Tilbury. Obsess CEO Neha Singh told me that the company’s mission is to replace the typical online shopping experience, which consists of “an endless scroll of every product looking the same size on a white background.” To that end, the Ralph Lauren Virtual Experience is successful. Still, while it isn’t boring, it’s kind of lonely. What’s missing in all of the virtual shopping environments I explored were other people walking by, talking, offering to help, looking at and touching things.

The loss of the human element is palpable. In the Lauren store’s shoe department, I watched a video with vignettes of people touching each other and engaging in high-risk activities such as gathering for the holidays. It left me wistfully remembering what I was missing in the world, and nothing I could do there, or anywhere else, could replace that.

Matterport client Ferguson addresses virtual shopping’s solitude by offering online appointments with its kitchen, bath, and lighting showroom consultants. Using Microsoft Teams, shoppers can share a virtual walk-through of a store, controlled by the consultant. While it might be a bit of a technical stretch for most shoppers to need Teams and a web browser just to pick out something from a shop, adding this social interaction to the retail experience recreates what’s missing in most virtual store experiences.

Ultimately, wandering in the marketplace is a centuries-old form of human connection and socialization, and a necessary social lubricant for communities. Stores that we can actually walk through in our neighborhoods offer us sights, sounds, smells, and human connections that support us as social beings, and the people who work in stores are inadvertent keepers of community knowledge. Replacing brick-and-mortar stores with virtual ones removes that critical aspect of community. With any luck, it will return after the pandemic.

For now, I’m enthusiastic about walk-through virtual store shopping. Even with its limited floor plan and inventory (World of Joy), or ads taunting me about a world of human behavior that’s currently on hold (Ralph Lauren), wandering anywhere outside of the house during this final lockdown push offers a bit of a desperately needed change of scenery. For the dark winter of 2020, being able to wander and connect with the marketplace outside the home in a somewhat familiar way is a holiday shopping winner.

S. A. Applin, PhD, is an anthropologist whose research explores the domains of human agency, algorithms, AI, and automation in the context of social systems and sociability. You can find more at@anthropunk and PoSR.org.

- 12-08-20

- connected world

How joining the e-bike revolution made my 2020 a lot more bearable

Instead of feeling trapped at home, I’ve been enjoying the great outdoors more than ever—even when pedaling up the scariest hills in town.

Last March, when the COVID-19 pandemic first disrupted everything, it took me a while to notice that my new lifestyle was one of extreme lethargy. With local businesses shuttered, activities canceled, and a second bedroom serving as my office, the amount of exercise I got on a typical day dwindled to a few hundred steps. Shuffling off to the kitchen for a snack started to feel like a workout.

After a month, I decided to confront the issue in a way that comes naturally to me: by purchasing a gadget. In this case, that gadget was an e-bike, something I’d been vaguely intrigued by for several years.

As much as I enjoyed riding my conventional road bike, the hills in between my home and the places I’d like to go had become a powerful disincentive to make it a major part of my fitness regimen. (The approach to our house is so steep that even kids tend to dismount and walk their bikes up it. ) An e-bike—which bolsters your own pedal power with an electric motor—seemed like it might give me fewer excuses not to ride.

In April, I bought a CityZen T9, an e-bike from Gazelle, a 128-year-old Dutch firm that’s a household name in its home market. Over the rest of 2020, rather than devolve further into couch potatohood, I’ve done more than 1,800 miles of e-biking. It’s been good for my state of mind, my weight, and my appreciation for the San Francisco Bay Area’s natural beauty. (I found further motivation to get out and about in my Garmin Vivoactive 4 smartwatch and the Strava fitness app, both of which help me track my journeys.)

The worst thing about e-bikes is paying for one. My CityZen T9 was $2,500–not counting upgrades I made to the tires, brakes, seat, and grips—which is more than the total cost of every other bike I’ve ever owned dating back to my boyhood Schwinn. Plenty of models cost far more than that. Prices are coming down, though: Rad Power, reportedly the U.S.’s largest maker of e-bikes, sells models that cost between $1,100 and $1,700. You can go even cheaper and end up with something basic but serviceable. (Electrek is a useful destination for reviews of not-so-pricey options.)

Still, when I measure the cost of my e-bike against the pleasure and utility I’m getting from it, I’m glad I splurged. I use it nearly every day—something that hasn’t been true of any new gizmo that’s entered my life since the iPad. And it’s my car that’s begun to feel like a supplemental form of transportation.

Here’s a GoPro video I made of one of my Gazelle expeditions, including me making my way past a protest on the Golden Gate Bridge:

The surprisingly controversial e-bike

My sudden, pandemic-derived interest in e-bikes was far from unique. As 2020 left many people pursuing new ways to exercise—and some folks looking for alternatives to public transportation—there’s been a boom in sales of bikes of all sorts. E-bikes, once a tiny niche in the U.S., have surged so fast that the industry is struggling to keep up.

The e-bike message boards and Facebook groups I visit are full of folks who love their new rides. I’ve run across only a few who regret the purchase. However, people who have never been aboard an e-bike sometimes have strange, prickly reactions to the whole idea of putting a motor on a bike.

When I tell people about my Gazelle, some seem to misunderstand it as being more motorcycle than bicycle, or solely a conveyance for senior citizens. Earlier this year, I heard a TV news personality (hint: Her name is Rachel) express on-air incredulity that one of her colleagues (a guy named Chris) had gotten a Rad e-bike. There are even ugly rumors of e-bicyclists being subjected to insults (“cheater!”) as they pass riders of conventional bikes.

I suspect that much of this confusion could be cleared up if the naysayers spent some time on an e-bike. My Gazelle’s Bosch motor system has four levels of assistance—Eco, Tour, Sport, and Turbo—and I do much of my pedaling in Eco mode, which provides only a modest boost. But it’s enough that I can go farther than I’d venture on an unelectrified bike, and without dreading any monster hills along the way. Is that cheating? If it is, so is coasting.

To me, the key factor about an e-bike is not how fast you can go, but how far. Published range estimates mean very little, since so many factors impact how quickly the battery drains. Those include your weight and cargo, the level of assistance you choose, and whether your route is flat or hilly. Even poorly maintained roads and gusts of wind will cut into your range. That said, I have found that I can ride my Gazelle for about 50 miles—enough to get me from my home south of San Francisco to the Golden Gate Bridge and well into Marin County, one of the nicest places in the world to go for a bike ride. And then all the way back home.

Bottom line: The rides that really don’t give you any exercise are the ones you never take. I’ve done far more bicycling in 2020 than in any previous year of my life, including some when I regularly cycled to work.

Tech on two wheels

After a few months of riding the Gazelle, I borrowed an e-bike from another Dutch company: a VanMoof S3. Unlike Gazelle—whose bikes are available through local bike shops—VanMoof sells its models via its website and a few company stores in big cities.

The S3 and another new VanMoof, the X3, made a splash in e-bike circles last spring when they debuted with price tags of just $1,998 apiece, compared to $3,398 for their predecessors. The impressive bang-for-buck led to long waitlists and some quality-control issues as the company tried to satisfy demand. (The first X3 the company loaned me was damaged in shipping, a problem that VanMoof told The Verge’s Thomas Ricker it acknowledges is happening to some buyers and has been working to address.)

The Gazelle feels like a conventional bike that’s been enhanced with a motor. The VanMoof, by contrast, has been far more thoroughly reimagined for the digital age. It shifts through its four gears for itself—like a car with an automatic transmission—and offers a Turbo Boost button that lets you rocket along even if you’re barely nudging the pedals. The built-in lock engages when you tap a button with your foot; before unlocking, it verifies that you’re the owner by connecting to VanMoof’s smartphone app via Bluetooth. The bike also has GPS, allowing it to beam its location back to you (or VanMoof) in the event that it’s stolen. Even its bell offers ringtone-like options, such as a party noisemaker effect that drove my neighbors’ dogs nuts.

And did I mention that this sleek, minimalist machine is one of the best-looking bikes I’ve seen, electric or otherwise?

But as I rode this bike, I sometimes missed the finer degree of control offered by my Gazelle. For instance, the S3 zipped up most hills but felt overtaxed on the steepest ones I encountered, perhaps because it has only four gears. (My Gazelle has nine.) On long trips, I like adjusting the Gazelle’s gears and assistance level on the fly to wring as much life as possible out of the battery. With the VanMoof, you don’t shift for yourself and can only change the level of assistance when you’re stopped—or by pressing the battery-sapping Turbo Boost button—which made its effective maximum range less than that of the Gazelle, at least for me. (On the plus side, it was much easier to pedal with the power off.)

When it came time to return the S3 to VanMoof, I was sorry to see it go. But if the company had been willing to accept my Gazelle instead, I wouldn’t have taken the offer.

The road ahead

As much as I’m enjoying my Gazelle e-bike, one question remains tough to answer: How much of a keeper will it be? In just the few months that I’ve been riding it, Gazelle has discontinued the model I bought and unveiled several new ones with various improvements. Over the next few years, it seems likely that VanMoof-like technical invention will become standard fare in the industry.

My old, unpowered Gary Fisher bike—which I still have, though it’s in storage at the moment—served me well for 15 years. With tune-ups, it will probably be eminently ridable a decade from now. But by then, it’s possible that riding a Gazelle CityZen T9 will be a bit like carrying an iPhone 3G in 2020. And I would need to have replaced the battery at least a couple of times, at an intimdating $850 a pop. Buying a new e-bike might look better than endlessly investing in an antique one.

However things pan out, I do hope that I’m e-biking in 2030 and beyond. I can’t quite decide whether it’s a healthy activity that’s fun, or fun that’s healthy. Either way, it’s guilt-free technology in an era that could use more of it.

About the author

Harry McCracken is the technology editor for Fast Company, based in San Francisco. In past lives, he was editor at large for Time magazine, founder and editor of Technologizer, and editor of PC World.

- 12-25-20

- world changing ideas

2020 saw a record drop in emissions—but it’s not the climate win it should be

There are ways to get this kind of climate win without also experiencing all the simultaneous pain.

After a record breaking wildfire season that burned more than four million acres on the West Coast, and a record-breaking Atlantic hurricane season that included 30 named storms (12 of which made landfall), the news that carbon emissions would drop a record 2.4 billion tonnes in 2020 seemed like a turning point for the climate. But taking a look around makes it clear that it had incredible costs. It’s a lesson in how we should—and shouldn’t—plan on lowering emissions in the future.

The 2.4 billion tonne deficit in 2020 was the equivalent of taking 500 million cars off of the world’s roads. “But we also need to remember that when you combine fossil emissions with land use emissions, we still will emit 40 billion metric tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere,” says Rob Jackson, a professor of Earth Sciences at Stanford University and chair of the Global Carbon Project. “That’s the number that really matters.”

Of course, the drop in our emissions came not because of smart climate policies, but because of COVID-19-related lockdowns that stopped commutes and shuttered businesses. That means that it required immense tragedy to achieve—and that there’s no indication that this drop in emissions will continue year over year, which is what’s required to decrease emissions enough to meet climate goals.

We’re already seeing this in China, where emissions are essentially back to 2019 levels. China had a shorter lockdown than the U.S., but even still, as their economic growth returned, so did their carbon emissions. It’s an example of how untenable this emissions drop is long term. “We don’t want emissions to drop because tens of millions of Americans are out of work, or hundreds of millions of people around the world,” Jackson says. “That’s not a sustainable path to climate action.”

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Climate experts have tried to drive home this point all year, that there are ways to get this kind of climate win without also experiencing all the simultaneous pain. The economy doesn’t have to suffer in order to decrease emissions; we can decarbonize the economy, create clean energy jobs, and get economic growth, Robbie Orvis, director of energy policy design at the nonprofit Energy Innovation, noted earlier this year. Global Footprint Network founder Mathis Wackernagel, when explaining how the pandemic moved back Earth Overshoot Day (the marker of when we’ve used up a year of our planet’s resources) pointed out that the goal is to move this date back “by design, and not by disaster.”

An important thing to watch going into 2021, Jackson says, is how stimulus funding is allocated for economic recovery. Unfortunately, so far, except for in Europe, “very little funding has gone to clean energy and tech,” he says, though the incoming Biden administration could change that in the U.S. The decisions we make next will matter far more than the fact that emissions dropped in 2020, and that impact will be felt for years to come. “We’re still reaping the benefits today of stimulus funding from 10 years ago,” Jackson says. “The record low solar and wind electricity prices we have today are because of stimulus funding went to provide incentives for renewable energy in the last recovery.” Those investments are still paying dividends today, he adds, and the investments we make now—in transportation like bike paths and electric vehicles and in more clean energy opportunities—could benefit us all for decades in the future.

A record drop in CO2 emissions isn’t a clear win; we are still so far from the finish line. What we need to do now is sustain that decrease while building back the economy—which is possible. At least two dozen countries have grown their economies while reducing their carbon emissions, and in the U.S. alone 41 states have done the same. “It isn’t climate and the environment or jobs, it can be both,” Jackson says.

Besides the drop in emissions, there have been other climate wins in 2020, like the fact that coal production dropped more than 20% in the second quarter of the year. It’s also notable that while overall electricity generation decreased by 3% this year, wind and solar still went up about 13%. “I don’t think the emissions drop because of a health and economic crisis should be the story of the year. I thought the story of the year would be the structural changes in clean energy production,” he says. That increase in wind and solar, even as electricity use dropped, is an actual win. “That’s something to celebrate,” Jackson says. “Those emission reductions will be sustained for decades.”

- 12-18-20

- connected world

Wearable gadgets could help catch COVID-19 before symptoms show

Early data suggests that continuous temperature monitoring could be more helpful than random fever checks.

Fever monitoring has developed something of a bad reputation under COVID-19. While having a fever is one of COVID-19’s telltale symptoms, temperature checks capture only a moment in time. Unless someone is stricken with fever, they tell us very little about a person’s state of health. But a new report suggests that body temperature can play a far more useful role in understanding health—we’re just using it wrong.

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, and the University of California, San Diego, have shown that constant temperature surveillance could be a promising method for detecting and predicting the onset of fever in COVID-19. In a 50-person feasibility study, researchers used the Oura Ring, a finger-worn sleep tracker, to monitor temperatures of participating healthcare workers and adult volunteers.

Everyone has a slightly different baseline body temperature. If that baseline starts to tick upward over a series of days, it may indicate illness. However, this study was not designed to definitively show that the Oura Ring—or any other temperature-tracking wearable—can predict COVID-19. This was merely a feasibility study, showing whether it’s possible to use this tech to conduct further studies into fever-related illness detection. Still, it represents a first step in understanding whether temperature monitoring can ultimately be used to detect or predict illness.

The study is part of an ongoing research project between UCSD and UCSF called TemPredict that hopes to understand the role body temperature, heart rate, and other physiological signals can play in predicting the occurrence of COVID-19 symptoms. The concept under investigation is whether data from wearables like the Oura Ring could be used to help public health officials navigate outbreaks like COVID-19 or even a regular flu season.

“For example, if you’re a public health official, you could have a weather map and just know a bunch of people are starting to get a fever in Seattle and [you] should go look at that,” says Benjamin Smarr, assistant professor of bioengineering and data Science at UCSD and lead author on the paper. “What this paper shows is that not only is that technically feasible, but that actually the physiology data seemed to do a much better job than the people of reporting when it is they seem like they are getting sick.”

A slow process

Tracking an outbreak like COVID-19 or any incident in public health can be slow moving, Smarr says. Public health officials have to wait until people are sick enough to go to a hospital or a doctor’s office and have their symptoms correlated to a particular disease. Then that data has to be reconciled with public health officials at the county level before a summary statistic is released.

“If people are willing to act as tracer particles, we could know within a day, if not in real time, where sickness events are happening,” Smarr says. Furthermore, he notes, public health officials could more quickly connect illness to either a specific disease outbreak or environmental effects such as weather, pollution, or accidents.

To use wearable-collected data would require a digital public health infrastructure that currently does not exist. The U.S healthcare system is frequently called a patchwork, but that would suggest that it’s in any way sewn together. In reality, each healthcare operator is its own carefully constructed garment. A person can amass a collection of different healthcare services, piecing them together much the way one does an outfit. This structure allows individuals to choose and shed services and systems based on what they think they need. This choice forces health systems to compete and, in theory, provide better care. In practice, it creates complications for public health efforts, as revealed by COVID-19.

While there is no public digital infrastructure currently that would allow for the kind of real-time health weather mapping that Smarr is envisioning, smart thermometer maker Kinsa has a program that gives a glimpse of what such a public health program could look like. The company works with schools that support students from low-income families to navigate flu season. Kinsa supplies families with smart thermometers and an app that records temperature data and symptoms and lets them text school nurses. School nurses get a platform where they can see anonymized temperature data for each grade. The system allows these schools and families to coordinate and reduce flu spread in schools.

Smarr says the difference between using a smart thermometer and a ring that constantly monitors body temperature is that a thermometer relies on an individual to experience symptoms and seek out a temperature measurement. It also captures only a single moment in time. The Oura Ring, by contrast, records broader and more nuanced temperature fluctuations over time, potentially giving public health authorities an ability to see an outbreak coming before it strikes.

The U.S. military is testing a version of this system. The Defense Innovation Unit, in collaboration with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, has paired a Garmin watch, the Oura Ring, and an analytics platform designed by Philips Healthcare to spot illness among troops before symptoms arrive. So far, it seems to be able to see illness coming two days beforehand. The program started with 400 participants in June but is expanding to 5,000, according to Defense One. Meanwhile, West Virginia University Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute is running a study that uses Oura to predict illness in healthcare workers.

To create a comparable system for the greater public, health officials would have to contend with privacy concerns. “I think there should absolutely be a public authority or even just a public record of the kind of physiological events that are happening,” Smarr says. “How you secure that and scrub individual information away from that is an interesting challenge.”

For now, using temperature as a beacon for public health status is merely in the research phase. Researchers at UCSF and UCSD have given the Oura Ring to 3,400 healthcare workers in various regions of the U.S., while Oura has enrolled more than 60,000 of its users. The results of the observational study are expected sometime next year.

About the author

Ruth Reader is a writer for Fast Company. She covers the intersection of health and technology.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK