Curb code rot with thresholds

source link: https://blog.ploeh.dk/2020/04/13/curb-code-rot-with-thresholds/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Curb code rot with thresholds by Mark Seemann

Code bases deteriorate unless you actively prevent it. Institute some limits that encourage developers to clean up.

From time to time I manage to draw the ire of people, with articles such as The 80/24 rule or Put cyclomatic complexity to good use. I can understand why. These articles suggest specific constraints to which people should consider consenting. Don't write code wider than 80 characters. Don't write code with a cyclomatic complexity higher than 7.

It makes people uncomfortable.

Sophistication #

I hope that regular readers understand that I'm a more sophisticated thinker than some of my texts may suggest. I deliberately simplify my points.

I do this to make the text more readable. I also aspire to present sufficient arguments, and enough context, that a charitable reader will understand that everything I write should be taken as food for thought rather than gospel.

Consider a sentence like the above: I deliberately simplify my points. That sentence, in itself, is an example of deliberate simplification. In reality, I don't always simplify my points. Perhaps sometimes I simplify, but it's not deliberate. I could have written: I often deliberately simplify some of my points. Notice the extra hedge words. Imagine an entire text written like that. It would be less readable.

I could hedge my words when I write articles, but I don't. I believe that a text that states its points as clearly as possible is easier to understand for any careful reader. I also believe that hedging my language will not prevent casual readers from misunderstanding what I had in mind.

Archetypes #

Why do I suggest hard limits on line width, cyclomatic complexity, and so on?

In light of the above, realise that the limits I offer are suggestions. A number like 80 characters isn't a hard limit. It's a representation of an idea; a token. The same is true for the magic number seven, plus or minus two. That too, represents an idea - the idea that human short-term memory is limited, and that this impacts our ability to read and understand code.

The number seven serves as an archetype. It's a proxy for a more complex idea. It's a simplification that, hopefully, makes it easier to follow the plot.

Each method should have a maximum cyclomatic complexity of seven. That's easier to understand than each method should have a maximum cyclomatic complexity small enough that it fits within the cognitive limits of the human brain's short-term memory.

I've noticed that a subset of the developer population is quite literal-minded. If I declare: don't write code wider than 80 characters they're happy if they agree, and infuriated if they don't.

If you've been paying attention, you now understand that this isn't about the number 80, or 24, or 7. It's about instituting useful quantitative guidance. The actual number is less important.

I have reasons to prefer those specific values. I've already motivated them in previous articles. I'm not, though, obdurately attached to those particular numbers. I'd rather work with a team that has agreed to a 120-character maximum width than with a team that follows no policy.

How code rots #

No-one deliberately decides to write legacy code. Code bases gradually deteriorate.

Here's another deliberate simplification: code gradually becomes more complicated because each change seems small, and no-one pays attention to the overall quality. It doesn't happen overnight, but one day you realise that you've developed a legacy code base. When that happens, it's too late to do anything about it.

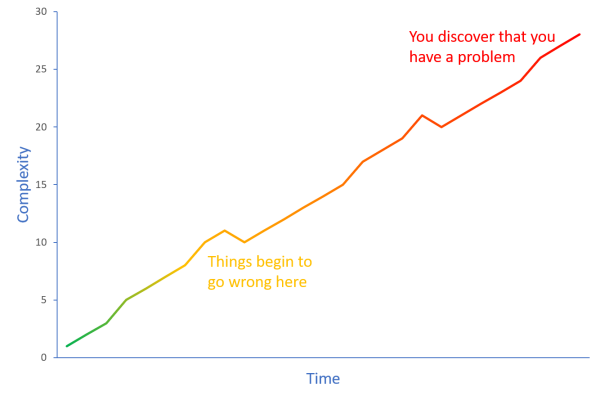

At the beginning, a method has low complexity, but as you fix defects and add features, the complexity increases. If you don't pay attention to cyclomatic complexity, you pass 7 without noticing it. You pass 10 without noticing it. You pass 15 and 20 without noticing it.

One day you discover that you have a problem - not because you finally look at a metric, but because the code has now become so complicated that everyone notices. Alas, now it's too late to do anything about it.

Code rot sets in a little at a time; it works like boiling the proverbial frog.

Thresholds #

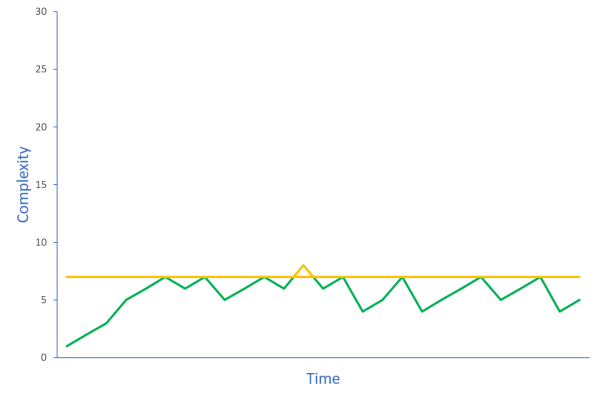

Agreeing on a threshold can help curb code rot. Institute a rule and monitor a metric. For example, you could agree to keep an eye on cyclomatic complexity. If it exceeds 7, you reject the change.

Such rules work because they can be used to counteract gradual decay. It's not the specific value 7 that contributes to better code quality; it's the automatic activation of a rule based on a threshold. If you decide that the threshold should be 10 instead, that'll also make a difference.

Notice that the above diagram suggests that exceeding the threshold is still possible. Rules are in the way if you must rigidly obey them. Situations arise where breaking a rule is the best response. Once you've responded to the situation, however, find a way to bring the offending code back in line. Once a threshold is exceeded, you don't get any further warnings, and there's a risk that that particular code will gradually decay.

What you measure is what you get #

You could automate the process. Imagine running cyclomatic complexity analysis as part of a Continuous Integration build and rejecting changes that exceed a threshold. This is, in a way, a deliberate attempt to hack the management effect where you get what you measure. With emphasis on a metric like cyclomatic complexity, developers will pay attention to it.

Be aware, however, of Goodhart's law and the law of unintended consequences. Just as code coverage is a useless target measure, you have to be careful when you institute hard rules.

I've had success with introducing threshold rules because they increase awareness. It can help a technical leader shift emphasis to the qualities that he or she wishes to improve. Once the team's mindset has changed, the rule itself becomes redundant.

I'm reminded of the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition. Rules make great training wheels. Once you become proficient, the rules are no longer required. They may even be in your way. When that happens, get rid of them.

Conclusion #

Code deteriorates gradually, when you aren't looking. Instituting rules that make you pay attention can combat code rot. Using thresholds to activate your attention can be an effective countermeasure. The specific value of the threshold is less important.

In this article, I've mostly used cyclomatic complexity as an example of a metric where a threshold could be useful. Another example is line width; don't exceed 80 characters. Or line height: methods shouldn't exceed 24 lines of code. Those are examples. If you agree that keeping an eye on a metric would be useful, but you disagree with the threshold I suggest, pick a value that suits you better.

It's not the specific threshold value that improves your code; paying attention does.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK