Questioning Probability

source link: https://justinmeiners.github.io/questioning-probability/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Questioning Probability

10/8/20

Are Elections Actually Random?

A popular narrative explaining the outcome of the 2016 election is that the odds were in Clinton’s favor. She just got unlucky. That election night, dice were cast, and she unfortunately rolled snake eyes. The comforting messages implied by this interpretation probably explains it’s popularity; it was nobody’s fault, we still have the popular ideas, we don’t even have to change our strategy to win next time. The alternatives are much harder to look at. But, the critical, yet unquestioned assumption that this narrative depends on is that elections are random events. But how similar is winning election to winning roulette?

Let’s briefly relate what actually happens on voting day. People wake up in the morning and make a decision whether to make their way to vote or not. They physically walk or drive to a voting location, and then choose who’s name to record, either by pushing a button or writing it in. Later, the votes are tallied and grouped by region and a winner is announced.

Where is the randomness? It’s hard to even find where variables might be changing rapidly. The media framework and campaign context is a product of months of effort. Each individuals broad political views are slow moving. They are driven by countless deeply rooted influences such as family upbringing, income, ethnicity, religion, education, culture. Undoubtedly all of this is very complex, much if it is unconscious and affected by PR and marketing, but nowhere do we see anything that looks like a random occurrence. It’s always cause and effect, and it’s not all that mysterious as you can probably make a good guess of how an acquaintance will vote.

You might argue this isn’t what is really meant when “chance” is talked about in elections. Journalists aren’t implying they function like a lottery. The percentages they throw around are confidence intervals. Pollsters can’t talk to everyone in the country, so they talk to a sample, and then use probability to guess how likely it is that this sample represents the whole population. It’s basic statistics.

But, even if the numbers come from such methods, this is not how they are presented by journalists and otherwise intelligent and “scientific” people don’t understand them that way either. If so, they would be much more concerned about finding specific gaps between the sample and population instead of wondering what the odds look like on their bet. Just look at how prevalent the random model is in these examples:

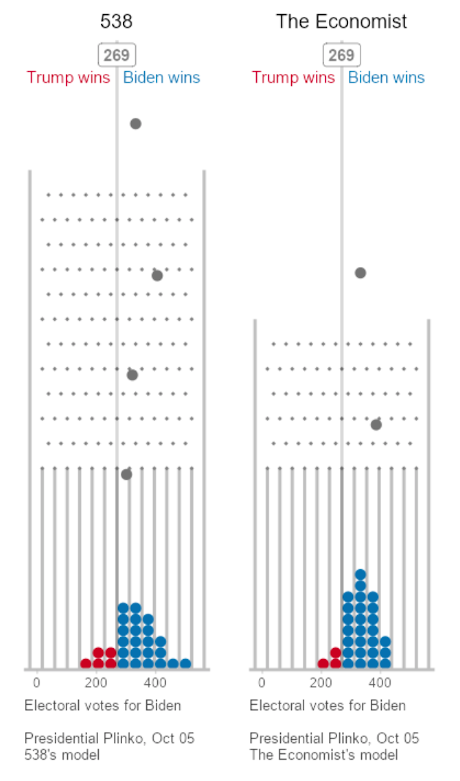

Election as a Pachinko Machine (1)

Let’s hope the people making these promotions aren’t the same as those making the models.

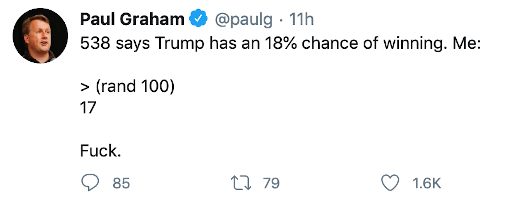

Election as an Unlucky Dice Roll

Unlucky again?

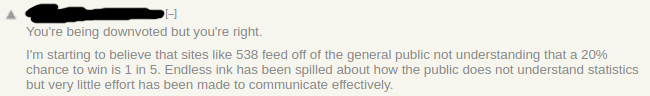

A Small Probability is still a Possibility

Perhaps students need fewer stats classes and more critical thinking.

Our Cultural of Randomness

Questionable applications of random thinking aren’t confined to politics. This reflects an underlying cultural trust and belief in the power of statistics. At first glance it appear to fit with our love of science and intelligence. Just look at all the numbers, equations, and graph. Everyone knows smart people use data to make decisions and it overcomes biases. Didn’t you watch Money Ball?

But this belief actually begins with our our basic physical view; the world is atoms crashing into each other in the void, and at the atomic level quantum events are happening which we don’t understand. Fundamentally, the future is indefinite, uncertain, and hazy. We can’t really plan or predict it. Sometimes we can setup Fleming or Darwinian-like projects to tip chance in our favor, but the best thing to do is leave all your options open to respond to unforeseen conditions. This indefinite attitude permeates our world with “lean startups”, index funds, zero interest, zero savings, extracurricular, and no planning. (2)

But let’s examine this views underlying underlying premise. How many things in our world are actually random? If you believe basic physics, it doesn’t appear anything at the scale of everyday life is really random. Every physical action is driven by cause and effect, which can be described at the human scale can be accurately using deterministic Newtonian relationships.

In computer programs it’s not even possible to obtain data which is truly random. Usually it’s just a function which is hard to predict, and uses varying inputs like time of data. Better sources sample from physical motion, like air vibrations. When random functions aren’t random enough, hackers can break encryption.

Just like the 2016 election, it doesn’t take scrutiny to realize that most subjects of statistical study are not actually driven by chance.

When is Probability Useful?

That is not to suggest that the entire field is misguided. Probability itself is a sound mathematical model, central to scientific inquiry. But, if the required axiom of having a random variable is virtually always false, then why should we ever hope to apply it in the real world?

We have already talked about one use case. Reasoning about a population from a sample. Ignoring the missing principle of uniformity in nature, and whether distributions are correct, this is still a helpful way to study large groups.

Another use case is when there are just too many variables to understand. When we have a cause and effect theory, but too many input variables, it’s overwhelming to use, so we settle for partial information. Consider a dice roll. Through classical mechanics we can understand gravity, the force of the throw, the friction in the air, the impact on the table, and with all this make an accurate description of the outcome. But no human can capture all those parameters in a split second and apply them. Without a controlled environment for study probability is a good model.

However, statistical physical models don’t just making random assignments. They tightly constrain the probability with deterministic mathematics, such as using regular formulas for area and force. (3) Furthermore, they never imply an underlying law of randomness. Rather they are useful compromises with tolerable inaccuracies.

The most common use case for statistics, and the one that needs to be scrutinized the most, is when you don’t really understand cause and effect relationships. Without a workable theory of nature, stats act as an adhoc placeholder. Data gets mapped to distributions, and patterns get correlated, without considering how the underlying objects works.

When this is your only option, it’s probably better than nothing. But, you have to be honest about the limitations. You definitely shouldn’t be surprised to find “black swans” when all you did is plot a bell curve, and hope everything else follows uniformly.

Consider two fields almost synonymous with stats; economics and psychology. Does anyone have a clear picture of how markets function, or the causes of inflation? Can anyone give an account of why people think and believe what they do? Of course not, and the popular theories change rapidly and dramatically. There are are a lot of variables in these domains too, so perhaps probability models are unavoidable. But clearly they are lacking in explanatory theories. Maybe a scientific theory isn’t even possible.

A Universal Way of Understanding

In The Republic X, Plato observes a related attitude in painting and poetry. He describes their practice as giving an appearance of understanding through shallow, and quickly made presentations:

The imitator, I said, is a long way off the truth, and can do all things because he lightly touches on a small part of them, and that part an image. For example: A painter will paint a cobbler, carpenter, or any other artist, though he knows nothing of their arts; and, if he is a good artist, he may deceive children or simple persons, when he shows them his picture of a carpenter from a distance, and they will fancy that they are looking at a real carpenter.

And whenever any one informs us that he has found a man knows all the arts, and all things else that anybody knows […] I think that we can only imagine to be a simple creature who is likely to have been deceived by some wizard or actor whom he met, and whom he thought all-knowing, because he himself was unable to analyze the nature of knowledge and ignorance and imitation.

And so, when we hear persons saying that the tragedians, and Homer, who is at their head, know all the arts and all things human, virtue as well as vice, and divine things too, for that the good poet cannot compose well unless he knows his subject, and that he who has not this knowledge can never be a poet, we ought to consider whether here also there may not be a similar illusion. Perhaps they may have come across imitators and been deceived by them

Statistics students and professionals hold the same remarkable belief about their own field today. They don’t need to study any subject or “applications”, besides statistics itself. Their statistical knowledge is immediately transferable to understanding any problem thrown their way, whether in tech, business, politics, finance, or healthcare. It’s a universal framework for understanding. This makes it the perfect career in the culture of randomness, and ironically minimize the need to make predictions about the future.

But can you understand business without running one? Can you understand voting patterns without understanding what is happening in people’s lives? Can you understand psychology without thinking, observing, and talking to people? Lack of basic knowledge and experience leave a lot to be desired. In these areas, as in politics, we can conclude that probability and statistics are poor substitutes for explanatory theory.

Notes

(1) Pachinko might be a good model to predict whether an INDIVIDUAL voter will make it to the voting location, as intended. Each peg represents an event encouraging or discouraging them (medical emergencies, flat tires, relationship trouble). But these don’t happen very often and the vast majority of those determined follow through with their intentions.

(2) For an exploration of these ideas see Zero To One by Peter Thiel.

(3) For a specific examples see the derivations for the equations of motion of gasses or how probability is used to estimating integrals.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK