Reflecting architecture and domain in code – @herbertograca

source link: https://herbertograca.com/2019/06/05/reflecting-architecture-and-domain-in-code/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Reflecting architecture and domain in code

This post is part of The Software Architecture Chronicles, a series of posts about Software Architecture. In them, I write about what I’ve learned on Software Architecture, how I think of it, and how I use that knowledge. The contents of this post might make more sense if you read the previous posts in this series.

When creating an application, the easy part is to build something that works. To build something that has performance despite handling a massive load of data, that is a bit more difficult. But the greatest challenge is to build an application that is actually maintainable for many years (10, 20, 100 years).

Most companies where I worked have a history of rebuilding their applications every 3 to 5 years, some even 2 years. This has extremely high costs, it has a major impact on how successful the application is, and therefore how successful the company is, besides being extremely frustrating for developers to work with a messy code base, and making them want to leave the company. A serious company, with a long-term vision, cannot afford any of it, not the financial loss, not the time loss, not the reputation loss, not the client loss, not the talent loss.

Reflecting the architecture and domain in the codebase is fundamental to the maintainability of an application, and therefore crucial in preventing all those nasty problems.

Explicit Architecture is how I rationalise a set of principles and practices advocated by developers far more experienced than me and how I organise a code base to make it reflect and communicate the architecture and domain of the project.

In my previous post, I talked about how I put all those ideas together and presented some infographics and UMLish diagrams to try to create some kind of a concept map of how I think of it.

However, how do we actually put it to practice in our codebase?!

In this post, I will talk about how I reflect the architecture and the domain of a project in the code and will propose a generic structure that I think that can help us plan for maintainability.

My two mental maps

In the last two posts of this series I explained the two mental maps I use to help me think about code and organise a codebase, at least in my head.

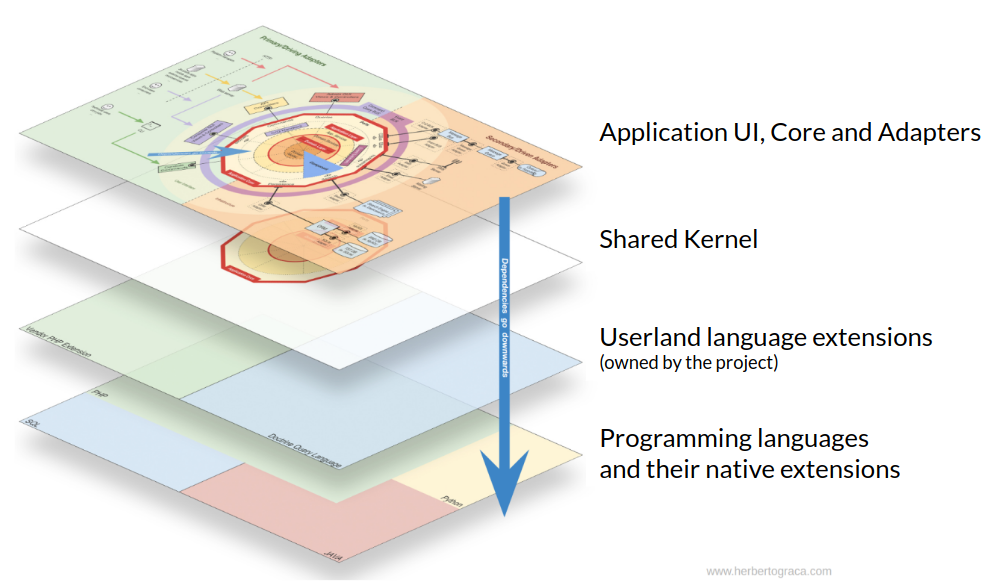

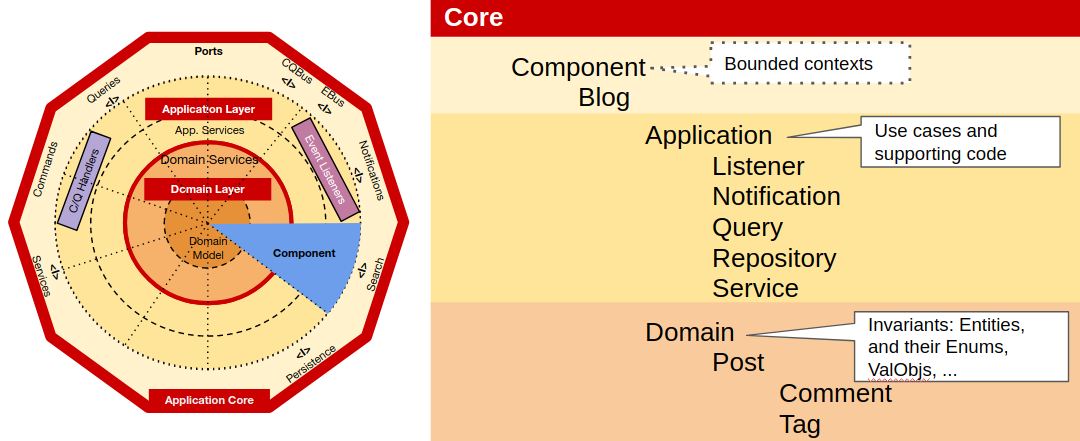

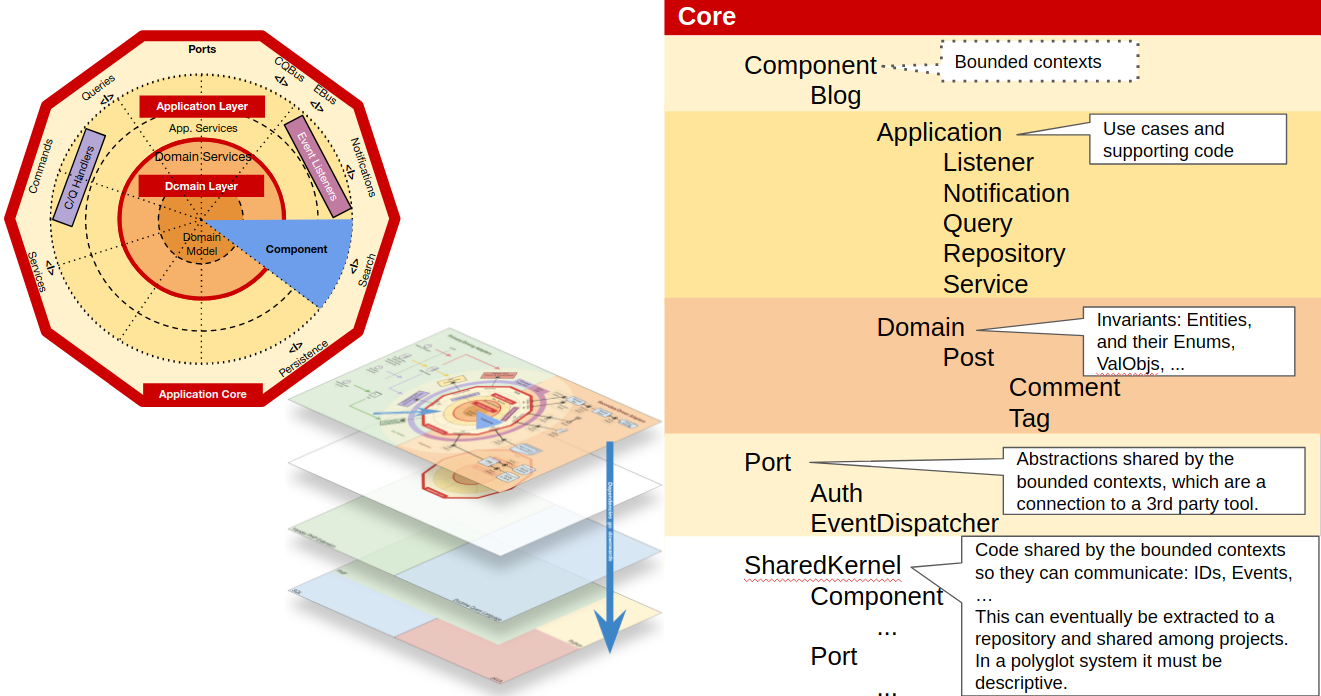

The first one is composed by a series of concentric layers, which in the end are sliced to make up the domain wise modules of the application, the components. In this diagram, the dependency direction goes inwards, meaning that outer layers know about inner layers, but not the other way around.

The second one is a set of horizontal layers, where the previous diagram sits on top, followed by the code shared by the components (shared kernel), followed by our own extensions to the languages, and finally the actual programming languages in the bottom. Here, the dependencies direction goes downwards.

Architecturally evident coding style

Using an architectureally evident coding style means that our coding style (coding standards, class, methods and variables naming conventions, code structure, …) somehow comunicates the domain and the architecture to who is reading the code. There are two main ideas on how to achieve an architecturally evident coding style.

“[…] an architecturally evident coding style that lets you drop hints to code readers so that they can correctly infer the design.”

George Fairbanks

The first one is about using the code artefacts (classes, variables, modules, …) names to convey both domain and architectural meaning. So, if we have a class that is a repository dealing with invoice entities, we should name it something like `InvoiceRepository`, which will tell us that it deals with the Invoice domain concept and its architectural role is that of a repository. This helps us know and understand where it should be located, plus how and when to use it. Nevertheless, I think we don’t need to do do it with every code artefact in our codebase, for example I feel that post-fixing an entity with ‘Entity’ is redundant and just adds noise.

“[…] the code should reflect the architecture. In other words, if I look at the code, I should be able to clearly identify each of the components […]”

Simon Brown

The second one is about making sub-domains explicit as top level artefacts of our codebase, as domain wise modules, as components.

So, the first one should be clear and I don’t think it requires any further explanation. However, the second one is more tricky, so lets dive into that.

Making architecture explicit

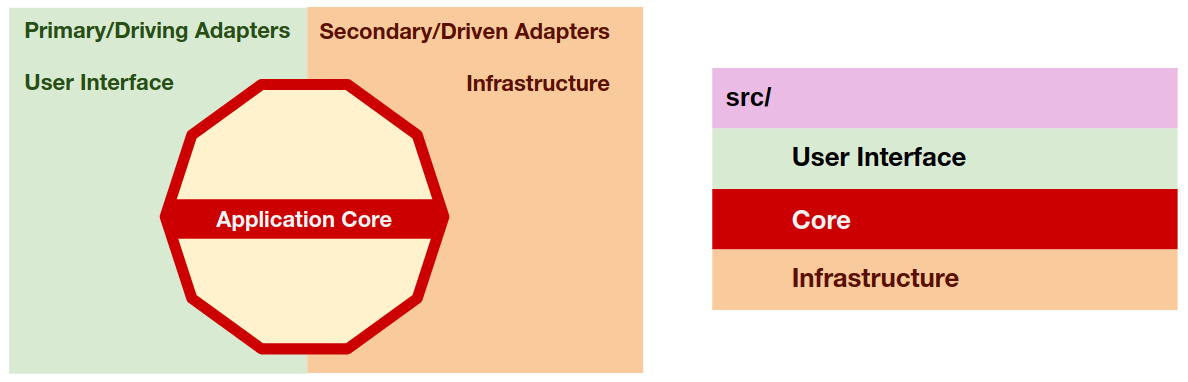

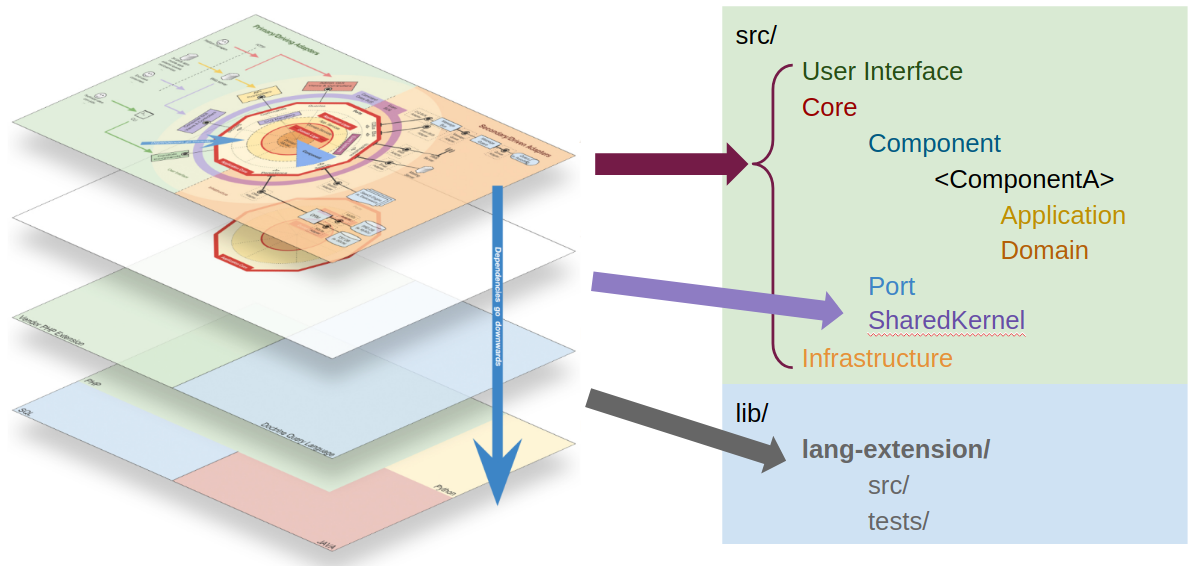

We’ve seen, in my first diagram, that at the highest zoom level we have 3 different types of code:

- The user interface, containing the code adapting a delivery mechanism to a use case;

- The application core, containing the use cases and the domain logic;

- The infrastructure, containing the code that adapts the tools/libraries to the application core needs.

So at the root of our source folder we can reflect these types of code by creating 3 folders, one for each type of code. These three folders will represent three namespaces and later on we can even create a test to assert that both the user interface and the infrastructure know about the core, but not the other way around, in other words, we can test that the dependencies direction goes inwards.

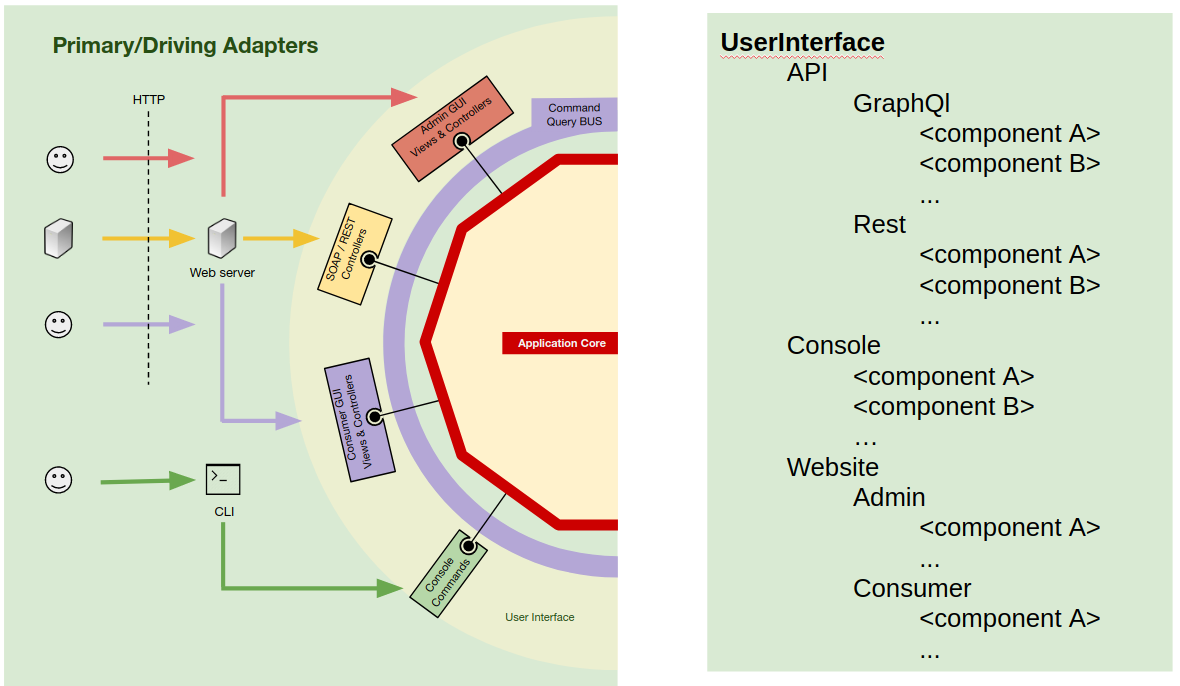

The user interface

Within a web enterprise application, it is common to have several APIs, for example a REST API for clients, another one for web-hooks used by 3rd party applications, maybe a legacy SOAP API that still needs to be maintained, or maybe a GraphQL API for a new mobile app…

It is also common for such applications to have several CLI commands used by Cron jobs or on demand maintenance operations.

And of course, it will have the website itself, used by regular users, but maybe also another website used by the administrators of the application.

These are all different views on the same application, they are all different user interfaces of the application.

So our application can actually have several user interfaces, even if some of them are used only by non-human users (other 3rd party applications). Let’s reflect that by means of folders/namespaces to separate and isolate the several user interfaces.

We have mainly 3 types of user interfaces, APIs, CLI and websites. So lets start by making that difference explicit inside the UserInterface root namespace by creating one folder for each of them.

Next, we go deeper and inside the namespace for each type and, if needed, we create a namespace for each UI (maybe for the CLI we don’t need to do it).

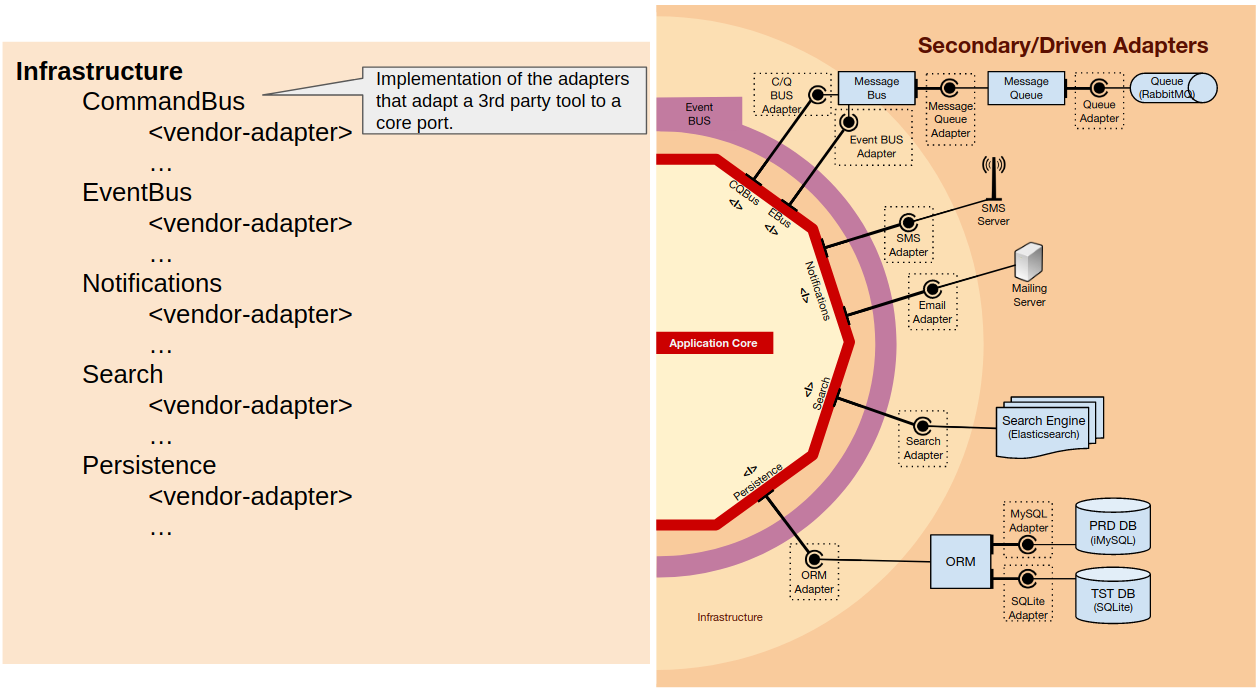

The infrastructure

In a similar way as in the User Interface, our application uses several tools (libraries and 3rd party applications), for example an ORM, a message queue, or an SMS provider.

Furthermore, for each of these tools we might need to have several implementations. For example, consider the case where a company expands to another country and for pricing reasons its better to use a different SMS provider in each country: we will need different adapter implementations using the same port so they can be used interchangeably. Another case is when we are refactoring the database schema, or even switching the DB engine, and need (or decide) to also switch to another ORM: then we will have 2 ORM adapters hooked into our application.

So within the Infrastructure namespace we start by creating a namespace for each tool type (ORM, MessageQueue, SmsClient), and inside each of those we create a namespace for each of the adapters of the vendors we use (Doctrine, Propel, MessageBird, Twilio, …).

The Core

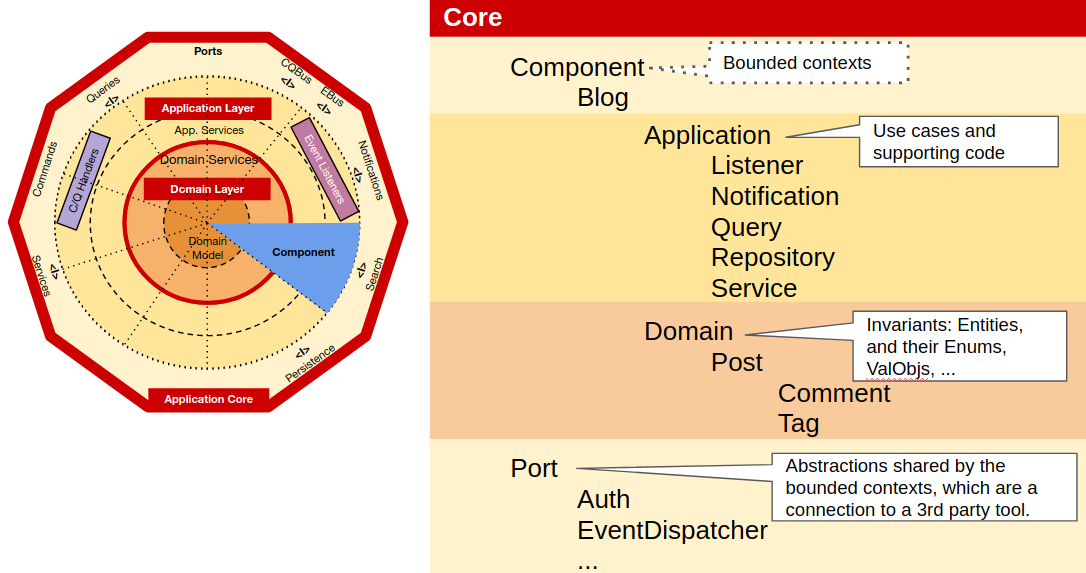

Within the Core, at the highest level of zoom, we have three types of code, the Components, the Shared Kernel and the Ports. So, we create folders/namespaces for all of them.

Components

In the Components namespace we create a namespace for each component, and inside each of those we create a namespace for the Application layer and a namespace for the Domain layer. Inside the Application and Domain namespaces we start by just dumping all classes on there and as the number of classes grow, we start grouping them as needed (I find it overzealous to create a folder to put just one class in it, so I rather do it as the need for it arises).

At this point we need to decide if we should group them by subject (invoice, transaction, …) or by technical role (repository, service, value object, …), but I feel that, whatever the choice, it doesn’t really have much impact because we are at the leafs of the organisation tree so, if needed, its easy to do changes to that last bit of structure without much impact to the rest of the codebase.

Ports

The Ports namespace will contain a namespace for each tool the Core uses, just like we did for the Infrastructure, where we will place the code that the core will use in order to use the underlying tool.

This code will also be used by the adapters, whose role is to translate between the port and the actual tool. It its simplest form, a port is just an Interface but in many cases it also needs value objects, DTOs, services, builders, query objects or even repositories.

Shared Kernel

In the Shared Kernel we will place the code that is shared among Components. After experimenting with different inner structures for the Shared Kernel, I can’t decide on a structure that will fit all scenarios. I feel that for some code it makes sense to separate it per component as we did in Core\Component (ie. Entity IDs clearly belong to one component) but other cases not so much (ie. Events might be triggered and listened to by several components, so they belong to none). Maybe a mix is the better fit.

Userland language extensions

Last, but not least, we have our own extensions to the language. As explained in the previous post on this series, this is code that could be part of the language but, for some reason, it’s not. In the case of PHP we can think, for example, of a DateTime class based on the one provided by PHP but with some extra methods. Another example could be a UUID class, which although not provided by PHP, it is by nature very aseptic, domain agnostic, and therefore could be used by any project independently of the Domain.

This code is used as if it would be provided by the language itself, so it needs to be fully under our control. This doesn’t mean, however, that we can’t use 3rd party libraries. We can, and should use them when it makes sense, but they must be wrapped by our own implementation (so that we can easily switch the underlying 3rd party library) which is the code that will be used directly on the application codebase. Eventually, it can be a project on its own, in its own CVS repository, and used in several projects.

Enforcing the architecture

All these ideas and the way we decide to put them to practise, are a lot to take in, and they are not easy to master. Even if we do master all this, in the end we are only humans, so we will make mistakes and our colleagues will make mistakes, it’s just the way it goes.

Just like we make mistakes in code and have a test suite to prevent those mistakes from reaching production, we must do the same with the codebase structure.

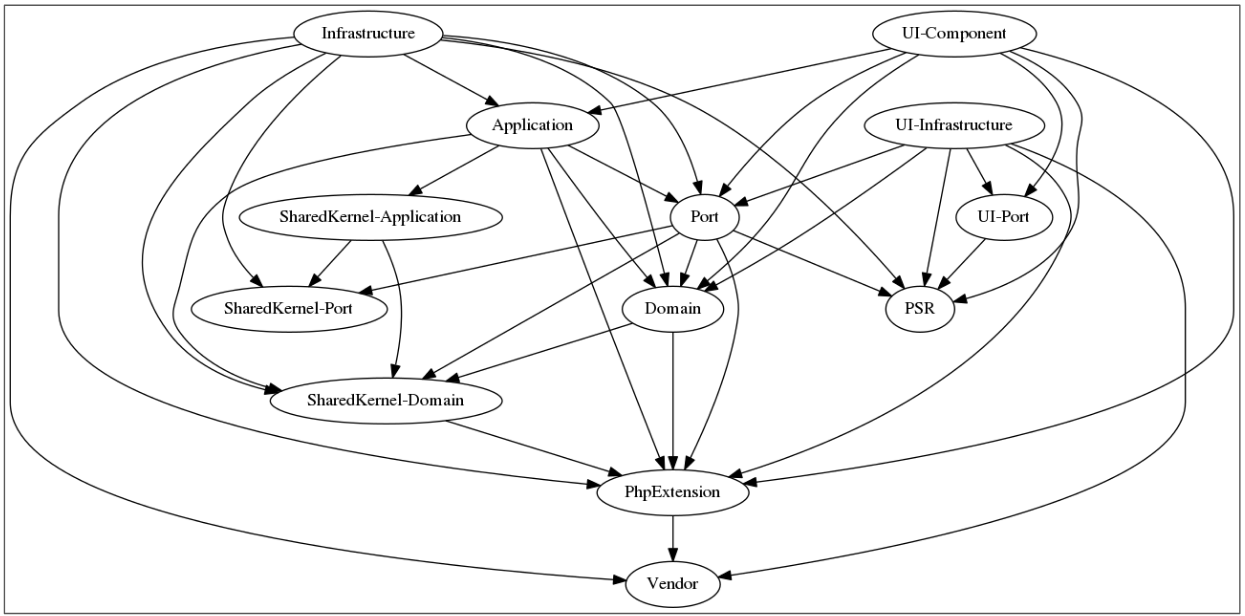

To do this, in the PHP world we have a little tool called Deptrac (but I bet similar tools exist for other languages as well), created by Sensiolabs. We configure it using a yaml file, where we define the layers we have and the allowed dependencies between them. Then we run it through the command line, which means we can easily run it in a CI, just like we run a test suite in the CI.

We can even have it create a diagram of the dependencies, which will visually show us the dependencies, including the ones breaking the configured rule set:

Conclusion

An application is composed of a domain and a technical structure, the architecture. Those are the real differentials in an application, not the used tools, libraries, or delivery mechanisms. If we want an application to be maintainable for a long time, both of these need to be explicit in the codebase, so that developers can know about it, understand it, comply to it and further evolve it as needed.

This explicitness will help us understand the boundaries as we code, which will in turn help us keep the application design modular, with high cohesion and low coupling.

Again, most of these ideas and practices I have been talking about in my previous posts, come from developers far better and more experienced than me. I have discussed them at length with plenty of my colleagues in different companies, I have experimented with them in codebases of enterprise applications, and they have been working very well for the projects I’ve been involved with.

Nevertheless, I believe there are no silver bullets, no one boot fits all, no Holy Grail.

These ideas and the structure I refer in this post should be seen as a generic template that can be used in most enterprise applications, but if necessary it should be adapted with no regrets. We always need to evaluate the context (the project, the team, the business, …) and do the best we can, but I believe and hope that this template is a good starting point or, at the very least, food for thought.

If you want to see this implemented in a demo project, I have forked and refactored the Symfony Demo application into using these ideas. You can check how I did it here.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK