Writing Documentation When You Aren't a Technical Writer – Part Two

source link: https://www.tuicool.com/articles/hit/jiUn6bV

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Writing Documentation When You Aren’t A Technical Writer — Part Two

Welcome back for Part Two of Writing Documentation When You Aren’t A Technical Writer! In Part One , we discussed how to write documentation people actually read and how to avoid the common pitfalls caused by code samples in your documentation.

In the fall of 2016, my teammate and I were tasked with the mission of improving my former company’s documentation and content. We spent a year working on all kinds of documentation — API references, guides, tutorials, and blog posts. I had been writing documentation off and on over the previous 5 years, but I wasn’t formally trained in technical writing. I was by no means inexperienced though, due to working on API documentation for projects and a startup and teaching Python Flask workshops towards the end of my computer science degree. This was the first time I had ever been able to focus on documentation, which allowed me to pursue my passion for helping people of all skill levels through technical documentation.

In that year, I learned a lot from the Write the Docs community, other API providers, and my own trials and errors. Last year, I spoke about it in a talk, “Things I Wish People Told Me About Writing Docs,” at the API Strategy and Practice Conference in Portland, OR. This multipart series is a survey of what I learned.

That’s all!

That’s all! :cold_sweat: It seems pretty harmless when you first read it out of context, but think of how certain words like “easy,” “simple,” “trivial,” and “not hard” make you feel like when you are struggling — not great! When you are stuck trying to get an API to work, encountering these terms can sometimes make you question your intelligence and ask yourself, “Am I being dumb?” It can be demoralizing.

Oversimplification

Oversimplification is all over our documentation. It is most common with people who are newer to writing documentation for others. Many times, the people who build the product are the ones writing the docs, so often certain things can seem “easy” to them. However, they are also the people that developed the feature, wrote the code for it, tested it many, many times, and then wrote the docs for it. After you do something dozens of times, it is understandable that something is “easy” to you. However, what about someone who’s never seen the UI or feature before?

Empathy

The language we use really matters. Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. We aren’t empathetic to our users when we use language like this. When we are empathetic to our users, we aren’t only helping the beginners, but, also the more advanced users. It helps grow the potential number of users, use cases, customers, and even $$$.

However, when the project’s expert developer is writing the docs, this can be harder. Here are a few helpful tips that have helped me in the past:

- Have people who are newer to the project give honest feedback on the docs in the review process

- Encourage people who are newer to the project to contribute to or address documentation that doesn’t make sense to them

- Develop an environment where asking questions is encouraged, including questions that may seem “obvious” to people familiar with the project — this helps you see your blind spots

- Use linters in your review and CI processes to make sure the language is empathetic and friendly to all users

- Lastly, ask for docs feedback from your actual users, put new docs in front of them and ask if they can follow them

Error messages as a form of documentation

Users are often more likely to see your error messages than your documentation. As Kate Voss says, “error messages are actually an opportunity.” I believe it is an opportunity that many people working on developer experience and documentation miss out on. It’s a place to educate, rebuild trust, and set expectations with your users. Most of all, it can help people help themselves.

I learned a lot about writing better error messages from Kate at Write the Docs . I also learned a ton from working on API error messages in the past, and I’ve been on the other side of the equation, consuming 3rd party API error messages as a developer.

Kate says the three H’s of good error messages are:

- Humble

- Human

- Helpful

Humble

Apologize first, even if it is not your fault. This is something I also practice when I jump into support tickets.

Example:

Sorry, we could not connect to ___. Please check your network settings, connect to an available network, and try again.

Human

Make sure to use human terms, avoid phrases like “exception has been thrown by the target of an invocation.” When writing code where many of our error messages are written, it is easy to not speak in human terms.

Example (401 Status Code Error from Twilio):

{

“code”: 20003,

“detail”: “Your AccountSid or AuthToken was incorrect.”,

“message”: “Authenticate”,

“more_info”: “https://www.twilio.com/docs/errors/20003",

“status”: 401

}

Helpful

If you remember anything from this, remember to be helpful. Share what the users can expect or do to fix the problem.

Example:

Sorry, the image you tried to upload is too big. Try again with an image smaller than 4000px tall by 4000px wide.

How to write error messages

Just like any other form of documentation, put the relevant information first. This can be done by having the object first and the action second. The user is looking for the result, not how to get there. This is helpful when users quickly scan your error messages.

Bad example:

Press the back button to return to the previous page.

Good example:

To return to the previous page, use the back button.

Errors in Docs

I find it really helpful when APIs put common error message strings from their API in the documentation. As someone writing documentation, it allows you to expand on the error message without increasing it in length, while still trying to help the user understand why they are getting the error.

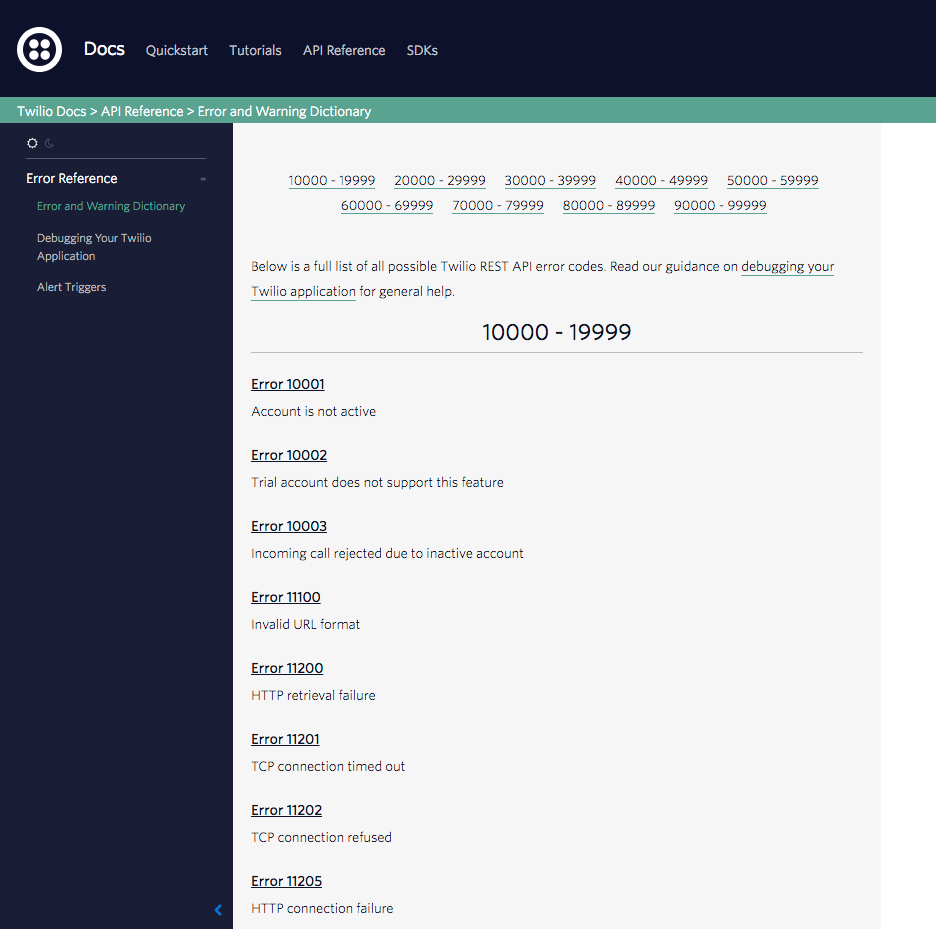

Twilio publishes their full Error and Warning Directory with possible causes and solutions. Using this method, you can keep your actual error messages shorter but still be helpful.

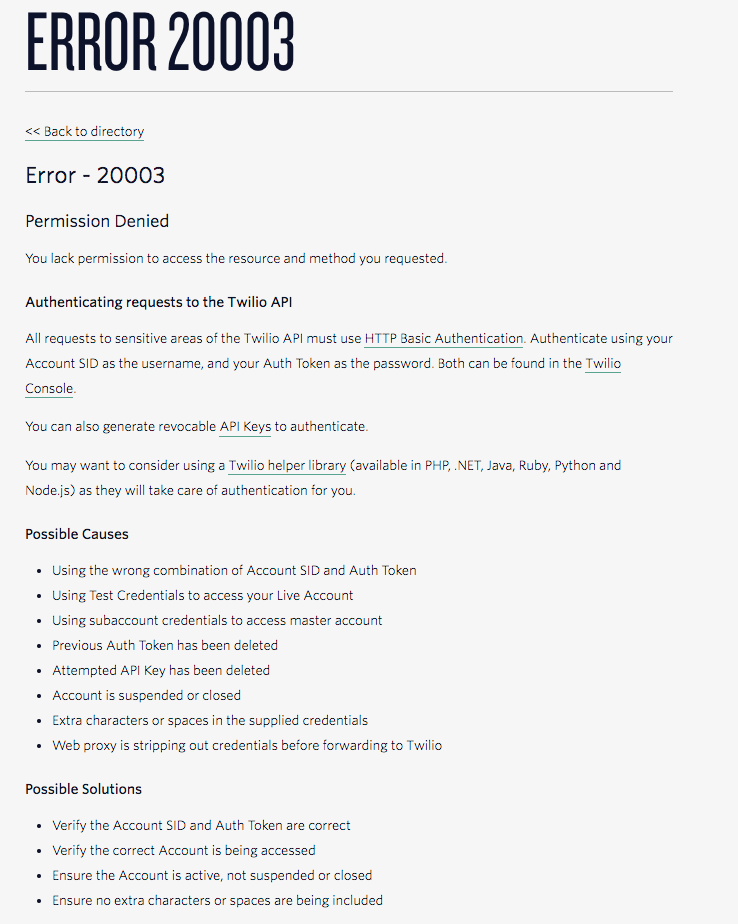

In the case of error 20003

(the 401 status code error from earlier), there are a lot of possible causes which they clearly lay out in their Error and Warning Directory.

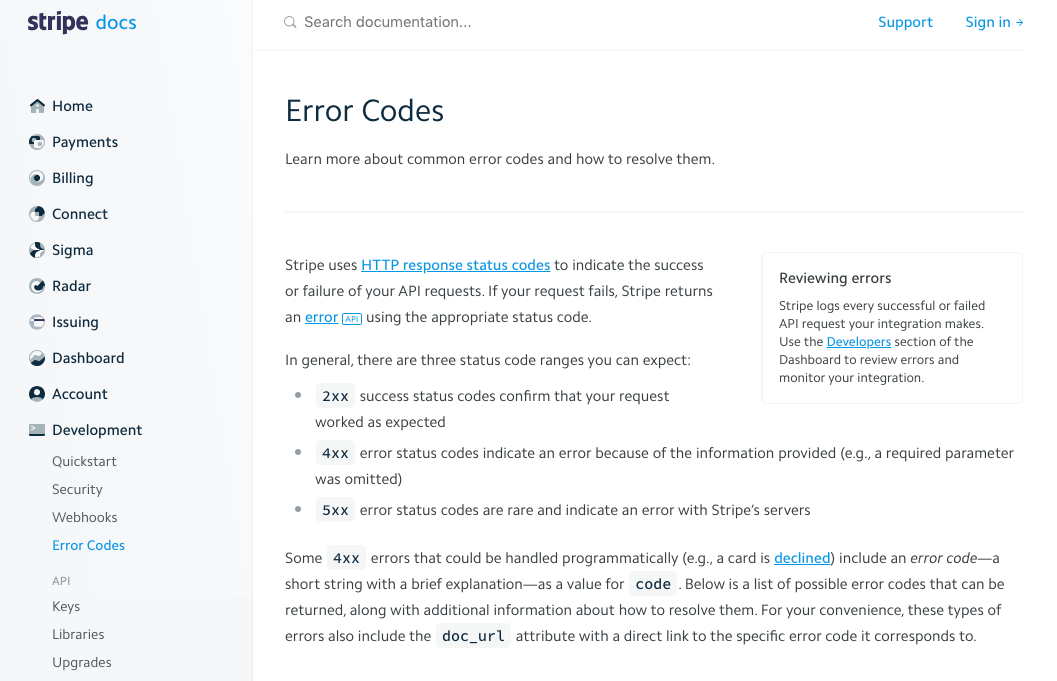

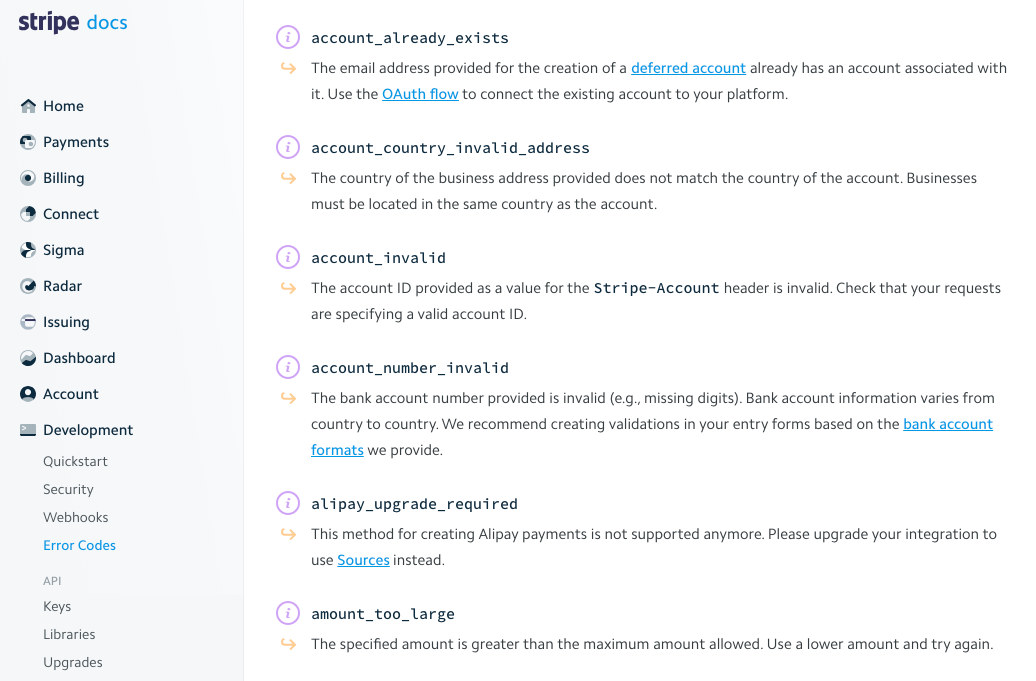

Stripe also does something similar with extensive descriptions of the different error codes.

You might even find your error messages in StackOverflow questions. Respond to these in a humble, human, and helpful way too. Because of SEO, it is common for users to end up on StackOverflow with your error messages and not your actual documentation.

Protip: If someone didn’t respond in a humble, human, and helpful way, it is possible to edit StackOverflow answers with enough “reputation”.

Word Choice

There are mental models for many words that already exist. For example, words like “libraries,” “SDKs,” “wrappers,” and “clients” are already overloaded, and you are walking straight into that.

In Ruthie BenDor’s talk, “ Even Naming This Talk Is Hard ” from Write the Docs, Ruthie talks about why choosing the right words can be so hard for us.

We are often bad at choosing what to leave out, even though we are doing it all the time when we write. Like the many names for an SDK, the names you give things are going to evoke all kinds of feelings, ideas, or definitions for your readers. You might not know what these are and we often make wrong assumptions.

The famous saying, “there are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things” feels very true in this situation. The quote is often attributed to Phil Karlton, but there are many variations of it today, like adding “off by one errors” or “diversity and inclusion” to the end of the quote. Ruthie maintains this demonstrates how much software these days is just an amendment to someone else’s code or work.

So why do bad names (or docs) persist?

Often, as with oversimplification, we don’t realize that the name is bad. This is what Ruthie calls “ empathy failure .” It’s like saying, the problems caused by the words don’t affect me, therefore they don’t exist.

Protip: Avoid accidental racism by using “denylist” and “allowlist,” instead of “blacklist” and “whitelist.”

(Sources: André Staltz and rails/issues/33677 )

To me, this is also similar to what Ruthie calls “ beginners’ mind failure .” This is like saying, “it is perfectly clear to me. I don’t understand how someone can not understand this.”

Lastly, Ruthie brings up that there can be “ localization failur e.” “What do you mean “bing” means “sick” in Chinese?”

According to the GitHub Open Source Survey from 2017 :

Nearly a quarter of the open source community reads and writes English less than ‘very well.’ When communicating on a project, use clear and accessible language for people who didn’t grow up speaking English, or read less-than-fluently.

Are you considering this when you use Americanisms and idioms in your docs? Many of these could be lost on your users.

Protip: I firmly believe that one of the greatest “tricks” to solve these failures is having a diverse and inclusive team working on documentation.

Then there are the cases where we recognize it is bad, but can’t, or won’t justify fixing it because we…

- Are tied to it

- Can’t justify the time

- Don’t know the value

- Don’t have the agency to fix it.

You might say or hear: “But this is my baby!” “Who moved my cheese?” “If we rename this, everything will be broken and on fire forever.” “I don’t believe that changing this name will move the needle on what we care about.”

We can’t be afraid to refactor and rewrite when it comes to our documentation. How will anything get better if we don’t accept that maybe you didn’t make the best choice initially?

How to choose your words wisely?

To help make this decision, I recommend first asking, “what words are your users using?” Different programming communities use different words, don’t try to use something that they aren’t. This is not only good for developer experience but even searchability and SEO.

In the end, it will inevitably be a judgment call and a balancing act. However, there are a few things to think about when you are evaluating how to say something. Ruthie says that bad names:

- Confuse

- Frustrate

- Misguide

- Obscure

- Offend

Moreover, good names:

- Make “aha!” moments happen

- Contextualize

- Explain

- Illuminate

- Empower

I recommend having these qualities considered when someone is reviewing your documentation. It helps give them things to look out for so that they can give you helpful and honest feedback.

The reality is word choice is hard. There are no magical formulas for it. All of our users and use cases are different; what might work for one set of users might not work for another. If it were easy, we’d all have a lot better documentation. As Ruthie says to developers, “writing software is an exercise in naming things. Embrace it.” And if you are writing docs for something someone else created, “let the developer know when their names miss the mark.”

I hope some of these tips help you the next time you are writing documentation. I’d love to hear what tips you’ve learned over the years that were helpful to you in the comments below. Keep your eye out for part three coming out in September, and check out part one from July .

We started a newsletter at Stoplight with some of the month’s blog posts, our favorite posts from the API community, and more! Sign up below :point_down:

Recommend

-

116

116

-

11

11

Six Tips for Interviewing Software Engineers When You Aren't Technical Mar 10, 2020 Interviewing engineers when you aren't one is a regular human resources task that tends to give non technical folk fits and f...

-

10

10

Writing - Technical - Writing API Documentation Jun 6, 2002 Writing : Technical : Writing API Documentation Last updated: 6/16/2002; 10:21:45 AM

-

7

7

About the roleHey 👋, we are looking for a member to join our team. Are you interested? About Webiny Webiny is a company with a mission to empower developers to create applications and websites on top of...

-

6

6

Throughout my life, I have been beneficially affected by many incidents, and technical blogging is definitely one of them. Throughout this article, I will paint a picture of me and my background in technical writing - where it came f...

-

14

14

What Is the Difference Between a Technical Writer and a UI/UX Writer By Aarthi Arunkumar Published 10 hours ago The...

-

6

6

关于 Technical Writer...

-

4

4

Introduction Technical writing is a highly demanding skill in the market right now because every organization needs someone to break complex terms into simple words to explain the product to the user. Not only the pro...

-

12

12

@edemgoldEdem GoldTurning Complex Concepts into stories. Contact Me: edemg...Receive Stories from @ed...

-

5

5

Technical Content Writer (Remote) (India)

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK