Why an Engineering Manager Should Not Review Code

source link: https://betterprogramming.pub/why-an-engineering-manager-should-not-review-code-46f87c08db66

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Why an Engineering Manager Should Not Review Code

Observing the Machine — Midjourney v5.1

When discussing team organization, I am often asked: “Why don’t you have the tech lead manage the team?” My response is to hiss like a vampire exposed to holy water. When the follow-up question is: “Given you want managers on your teams, can the manager still perform code reviews?” I burst into flames.

This question comes up all the time. But, let’s think about this question (and my response) a little deeper.

- Why shouldn’t the tech lead manage the team?

- Why shouldn’t the engineering manager perform code reviews?

Like everything in technology, the answer depends on the situation. Here I attempt to answer the perennial question of “Why should the TL not lead the team and why should an EM with a team of sufficient size not review code?”

We consider three aspects when answering this question: role definition, team communication complexity, and team size. Let’s unpack my reasoning with helpful graphics. Warning: very light math ahead.

The difference between the Manager and the Tech Lead Roles

First, let’s tackle role definition. Engineering manager and technical lead are two different roles with different skill sets. Someone might be good at one role but not the other (and vice versa). For example, the best programmer on the team is not always the best person to organize all the stuff.

However, the team needs both roles to operate optimally. So let’s compare and contrast the roles.

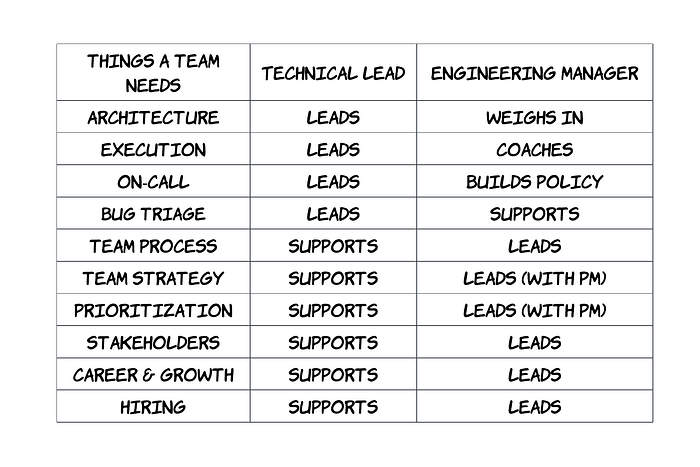

Difference in Role and Responsibility between TL and EM

This table is why, when an engineer asks to become a manager, I start with a round of “Are you sure are you really sure are you really really sure” questions — because these are very different roles.

This table reflects a partnership between the Technical Lead and the Engineering Manager — a division of labor between the organizational and communications labor and the hand’s on technical deep thinking. The roles are equals in level and scope across the team, but they perform different activities to support the team’s success.

For the manager-lead partnership to work, they need to build trust between themselves.

- The manager should delegate the team technical leadership to the technical lead and get out of the weeds. Managers should not fall off the bus and forget decades of technical background. However, managing is fundamentally a policy job, and managers should respect boundaries. Anything else is micromanaging and breaking trust.

- The technical lead should delegate the career, team growth, communications, and coordination work to the engineering manager and focus on architecture, technical choices, technical direction, and helping to drive execution.

However, this manager/lead distinction doesn’t need to exist until the team has at least 4 people. Below that team size, lines blur. After a team size >= 4, the roles split, and engineering manager should focus on the team and invest in a trust partnership with the technical lead.

Let’s see why that size >= 4 is an inflection point.

O(n²) communication complexity

Second, let’s talk about communications. A manager builds a well-working team on solid communication fundamentals. As we add members to the team, communication paths on a team multiply. We intuitively think team communication complexity grows in O(n) as we add people to the team, but here, the Mythical Man Month is 100% on point.

Communications complexity on a team grows (n * (n-1))/2) as new people join the team—or O(n²) quadratic time.

- At first, you are the only person on your team, so you spend all day talking to yourself. 0 communication paths, and remember to take health breaks.

- You add 1 person A to your team. Now you talk to A, and A talks to you — 1 communication path.

- You add 1 person B to your team. So now you’re managing 3 communication paths — you — A, you — B, and A — B.

- You add 1 more person C to your team. So now you’re managing 6 communication paths.

- And so on.

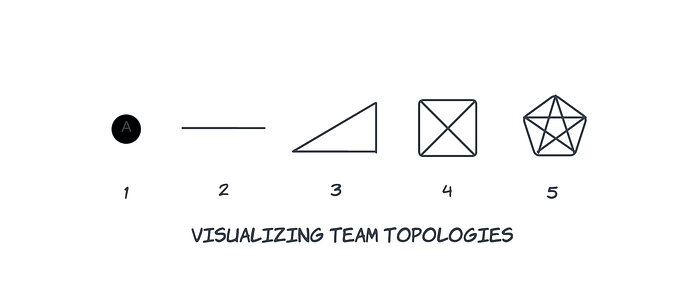

Visualizing the communication paths in a team — everyone must speak with everyone!

Once we’ve built a team of 5 people (6 total, you + 5 engineers) and add a Product Manager and a Data Scientist, the team’s manager must keep 26 ((8*7)/2) team interconnected communications pathways flowing unblocked so the team can execute. Toss in a few partner teams and engage with marketing, sales, and customer service — managing the team suddenly becomes a day job.

All these communication interconnections represent an investment in time. The manager is the spider in a web of complicated communications, including:

- Communicating extreme clarity of prioritization,

- Driving team execution,

- Coordinating status and releases with stakeholders,

- Operating team processes smoothly,

- Communicating team and individual goals, expectations, and performance for career growth,

- Untangling team communication knots,

Simply managing the meetings around the team becomes complex as the team grows. The negative side of team growth is called the diseconomies of scale — the more scale added to the system, the more rigid the system becomes and the higher the complexity overhead. This complexity is why standups grind to a halt the more people in the meeting.

And the team cannot scale infinitely — adding infinite people to the team will cause the team to implode. At communication interconnections equal to or greater than Dunbar’s number, the manager can’t manage the communication complexity themselves anymore. The threshold is about 17 different people (136 connections) before the manager has to start prioritizing relationships, breaking the team up into two, or delegating further.

The explosion of complexity doesn’t explain why the manager shouldn’t code but does describe why the manager’s calendar turns into that “classic manager’s calendar” at a particular team size, and time becomes a premium.

Let’s plot this out and see what is going on visually.

The Team Size Curve

Third, we’re going to talk about communications to team size. We’re all engineers here. If we can do anything, it’s plot stuff.

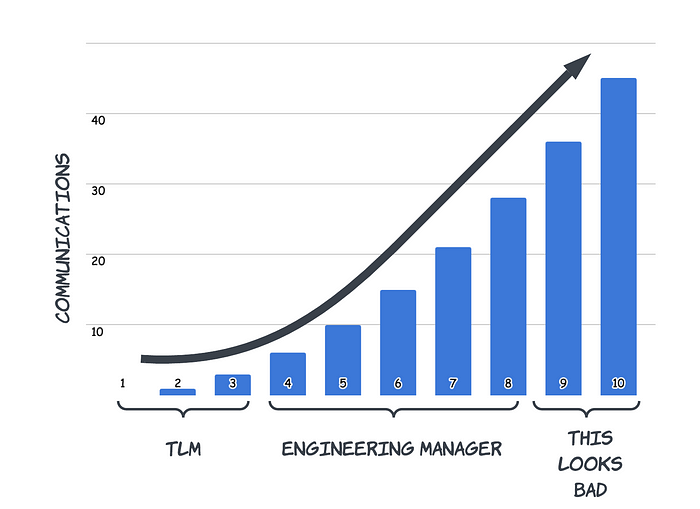

We plot the complexity of interconnected communications and team size to see when the manager should pull themselves out of the technology and focus on the communications overhead required for a well-functioning team. (We include the manager in the counts, so these counts are manager + engineers.)

Plot of team size vs communication interconnections

At 1–3 team members, the communications interconnections are manageable by the group. It’s still small and light. And, at this size, the team leader can perform the role of a Tech Lead Manager (TLM) — a leader of a small technical team who can still write code and perform technical functions while maintaining many aspects of the manager role: growing engineers, conducting performance reviews, managing the overhead of collaboration with nearby teams, etc. The communications overhead has not yet become overwhelming, and it is possible to wear both hats.

The laws of quadratics bites after 4, when there are 6 paths to keep reconciled. 6 doesn’t feel like much overhead, but start thinking through growth, performance, prioritization, and alignment for 4 people and it takes just enough time investment that technical output begins to wane and something must give — either the output or the fidelity of the communications — if one person performs both roles. Engineers stop growing. Code stops shipping. Team becomes confused over the most important things.

4 is the magic number when the TLM must make a choice between Technical Lead or an Engineering Manager, but not both.

Once we’re to 5 team members, TLM-ing is right out. What happens if no one steps up and takes on the communications role for the team? More often than not, the team collapses into thrash and stops moving forward on their priorities. The team and their stakeholders are too confused. Someone has to establish clarity and process to allow engineers to do what they do best: make awesome things. That role is a full-time job.

Interconnected communications complexity is also why large teams naturally break down into sub-teams of 1–3 people to focus on a project. At team size 1–3, communication overhead is manageable, and technical work gets done. But, once adding the 4th person, we’ve entered the world of the team size curve…

An Aside: On TLM-ing

It would seem that the TLM role is the ideal one that allows a leader to perform some people management and technical work and encompasses the best of both worlds. Moreover, for small companies, converting a technical lead to a TLM is a convenient hack for building a team quickly.

But TLM is not a long-term position because, ultimately, the roles of Technical Lead and Engineering Manager are different. As a result, TLM is a dead-end: performing two roles at once (badly) without being able to drive the scope (technical or teams) of someone dedicated to one or the other. Ultimately, the TLM will need to pick one lane or the other to invest 100% of their time or become stagnant as they cannot grow scope.

Why an Engineering Manager should not do code reviews

Finally, pulling these tracks together, we’ve establishing two facts:

- Technical Lead and Engineering Manager are two roles that partner to make the teamwork. Therefore, they should have clear roles and responsibilities and cooperate in a mutual partnership.

- Teams hit a size inflection point of ~4 where someone must dedicate their time to communications for the team to work. Otherwise, the team collapses into a black hole of thrash.

At a team size of >= 4, an engineering manager should focus on their core role — managing the communications within and outside the team, focusing on engineer growth (also communications), and understanding the team’s priorities (yet again communications). And at team size of >= 4, the technical lead should focus on architecture, technical choices, and the team’s technical work. Divide and conquer is how the team succeeds.

Unpacking how we get to the end:

- The core role of an engineering manager is to manage communications within and without the team — including career, performance, planning, and setting team processes. This communications job is a significant investment in time.

- After a sufficient team size, the manager must trade off technical acumen for investment in alignment and communications because the communications interconnections are high.

- And at sufficient team size, the communications overhead may be so high that the manager must pick and choose or be overwhelmed by that job alone due to the complexity.

- An engineering manager reviewing code is not only neglecting their core role but micromanaging the technical lead. This activity is a breakage of trust.

- And not only is it micromanaging, it’s also condescending to the technical lead.

- This does not mean the engineering manager cannot participate in technical discussions (especially architectural reviews), but the technical lead drives the technology.

And thus, why an engineering manager with a team of sufficient size should not review code. Trust, delegation, and communication are the core of the engineering manager’s role, and that’s what it’s all about.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK