How risk scores could shape health care.

source link: https://slate.com/technology/2022/09/health-care-risk-scores-insurance.html

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Can Your Health Be Boiled Down to a Single Number?

An expert on health economics and predictive analytics responds to B. Pladek’s “Yellow.”

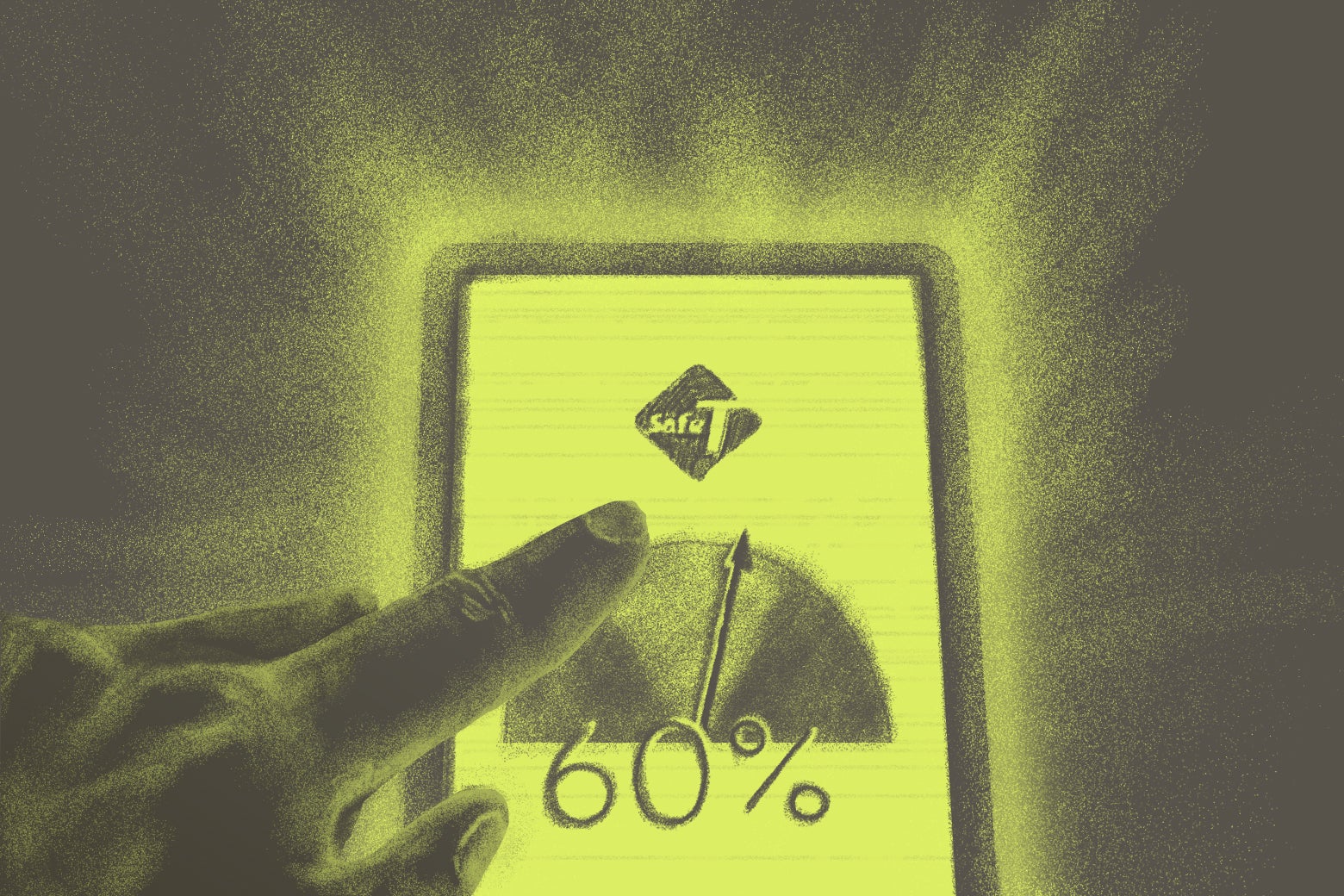

If a medical treatment for a life-threatening disease had a 60 percent chance of success, but another treatment with a 50 percent success rate had a lower risk of bankrupting your family, which would you choose? What if the success rates were 95 and 90 percent? Would you change your answer?

How we use probabilities like these to guide our choices is at the heart of “Yellow,” a new Future Tense Fiction story written by B. Pladek. The story’s main character, Chase, works for a private company that helps people navigate these numbers. One of Chase’s clients, for example, is a mother with stage-three cervical cancer who must choose between radiotherapy (60 percent success rate, 80 percent bankruptcy risk) and chemo (50, 65 percent). Is a 10-point increase in the chance of survival worth the 15-point increase in the risk of bankruptcy?

For any patient, this is a difficult decision to make—and, for better or for worse, cancer patients today don’t yet benefit from risk estimates as precise as those Pladek imagines. But quantifying the risks associated with each treatment option is essential for patients to understand the nature and magnitude of the trade-offs involved, even if it doesn’t make the ultimate decision any easier. Moreover, these dilemmas, and the treatment choices patients eventually make, signal to health care providers which features of existing therapies they need to improve—which in turn benefits future generations.

Getting these percentages wrong harms current and future patients alike. For instance, if providers overstate the effectiveness of radiotherapy or understate its associated bankruptcy risk, current patients may be misled to sacrifice too much financial health in return for a smaller-than-expected return in terms of physical health. And when current patients accept inferior therapies, their choices send the wrong signals to the developers of new therapies, harming future patients.

How to set up efficient markets for such high-stakes medical treatments is far from obvious.

For starters, it is practically impossible for patients to detect on their own when the risk estimates of competing therapies are off. These are not easily verifiable predictions. By contrast, each time we check the weather forecast, read a stock picker’s report, listen to a podcast’s predictions on how our favorite football team will do this weekend, or consult a route planner for predicted traffic patterns, we can observe how accurate these predictions are over time. By rewarding providers of more accurate forecasts with greater market share, we encourage investment in better prediction technology. More accurate forecasts in turn attract more users, reinforcing the incentive to improve. This virtuous cycle breaks down when forecasts are used so rarely that individuals cannot reliably assess their accuracy. The success rates of cancer therapies and lawsuits are prime examples. Although a 60 percent success rate, expressed as a 10-year survival probability, would lead us to expect Chase’s patient to live at least another decade if she chose radiotherapy, her death before reaching that milestone would not imply the prediction was wrong—after all, her chance of survival was only 60 percent. As Chase observes pointedly, “your number wouldn’t protect you.”

While your number won’t protect you, insurance against an adverse treatment outcome can, to some extent. For major, yet infrequent medical interventions such as cancer therapy, bariatric surgery, heart-bypass procedures, or joint replacement, providers could offer to compensate patients for failing to achieve well-defined treatment outcomes, such as surgical complications, recovery time, preservation or restoration of physical function, and survival. Analogous to auto or life insurance, patients’ medical histories, clinical profiles, and possibly a preoperative exam would allow providers to offer personalized insurance quotes. Providers, then, could back-up promises of better patient outcomes with outcome warranties that would replace the costly and inefficient litigation pathway to resolve such cases. Medtronic, a large medical device manufacturer, is already experimenting with rebates to convince skeptical surgeons of the effectiveness of its devices. By soliciting premium quotes from competing providers, patients could infer quality differences among providers by comparing their warranties. Your number won’t protect you, but it can set expectations.

Predictions become more complex, and more tempting to manipulate, when they inform our choices, and our choices in turn affect those very predictions. If your route planner predicts a traffic jam, should you believe it? What if, in anticipation of the traffic jam, everyone takes an alternate route, thereby preventing the traffic jam from forming? But what if, in anticipation of everyone else switching to an alternate route, everyone reverts back to their original route and thereby cause the traffic jam as it was forecast originally? When this process of adjusting expectations has reached an equilibrium point, the traffic jam will form, although it will not be as long as originally forecast. It will be just long enough to deter the believers of the forecast from taking the original route and short enough to invite the doubters. Paradoxically, the more we trust a prediction, the more suspicious we should be of it.

In “Yellow,” a similar dynamic plays out between Chase and his wife, Tara—who are split both in their trust of the risk assessment system and their tolerance for risk itself. This is nowhere more apparent than when they consider how much they should believe the “overall safety number” for Whitefish Beach, an index that reflects the risks of, among other things, unrest and contagion. As they both ultimately suspect, the consortium that publishes this number may try to misstate these risks to influence would-be protestors and saboteurs in their decision to travel to Whitefish Beach. But the more the consortium distorts the true prediction, the less credible its risk estimates become and the less it will be able to influence subsequent decisions. The consortium’s optimal degree of distortion will balance the benefit of exploiting its credibility (and thus influence) against the risk of eroding or destroying entirely that credibility in the process: We should expect it to rig the published risks of unrest and contagion sometimes somewhat, but not too often and not too much.

As the story progresses, Chase grows more and more suspicious of the increasing, and increasingly implausible, overall safety number for Whitefish Beach. How we view and use predictions, particularly those relating to our safety and health, is intensely personal. It also is a task unprecedented in human history. Never before have we had access to this volume of personalized risk estimates. Nor have we had to decide how far to allow them into our lives. For instance, combining data derived from wearables, health care use files, electronic medical records, patient registries, and social media enables increasingly precise predictions of who may develop a rare disease—even before that person has shown any symptoms or undergone any diagnostic testing. When risks like these suddenly become visible to us, we must ask: What do we each gain by tracking them?

In the end, Chase is able to confirm his suspicion and break his unproductive spiral of rumination when he contrasts the published safety number with the list of injuries that his employer is forecasting for Whitefish Beach. His approach suggests that our best hope of promoting impartial and accurate risk assessments may be to foster competition among prediction publishers who can draw on a wealth of diverse data sources. Yet, when accurate predictions rely on large volumes of user data, competition tends to give way to market concentration. Analogous to the network effects that drive market concentration in social media, any sort of successful predictive platform (say, Waze for traffic) will come to dominate its market. In a medical context, the more patients who share their experiences with a given prediction platform, the more patient data that platform can draw on to improve its predictions, in turn attracting even more patients.

Social media platforms have shown us the immense benefits of such network effects when they improve our access to information. They also have shown us the potential for harm when they unduly influence our choices. We haven’t yet resolved how to curb the influence-seeking abuse without jeopardizing the information-sharing benefits that such highly concentrated power makes possible, but it will be essential to do so before the ever more sophisticated predictive platforms envisioned by Pladek are widely available.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK