Design 4.0: leading design in the new industry

source link: https://uxdesign.cc/design-4-0-leading-design-in-the-new-industry-2720fefb89ff

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Design 4.0: leading design in the new industry

Is there a need for designers to up their skills and knowledge in the new industrial revolution? Yes, but it comes with its own set of challenges.

The art community is going through a terrible storm of words over the latest annual art competition at the Colorado State Fair. As it turns out, the artist, Jason M. Allen, won a prize for his work, “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial.” The catch? It was done with a line of text through an artificial intelligence program called Midjourney. Artists are disillusioned as they sense the beginning of the end is there in the writing. As the creator, Allen, said, “Art is dead, dude. It’s over. A.I. won. Humans lost.”

While the art community continues to grapple with the emergence of DALLE-2 and GPT-3, an invisible force known as Industry 4.0 is at play, and none of us are out of the woods. In fact, the world is not putting the brakes on technological progress either. Rather, both producers and consumers are gradually embracing the transformative effects it has on society and the economy.

Where does this leave the designer, and how do we embrace this new era? Perhaps there is a way to look at this from a half-cup-full perspective. To do this, we should understand how Industry 4.0 got to where it is today.

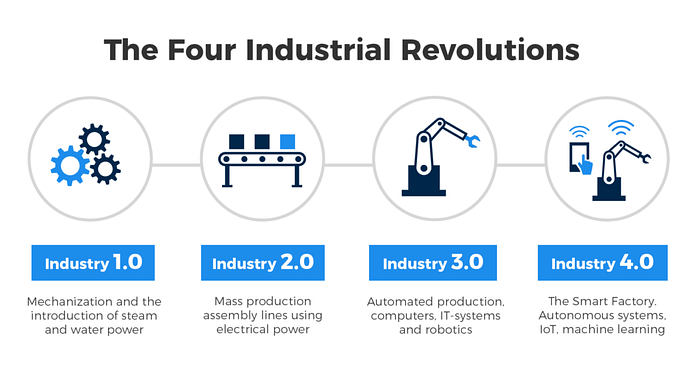

The Four Industrial Revolutions

In Industry 1.0, dating back to the 18th century, steam-powered machinery, allowing people to free themselves to work with their bare hands or with simple tools.

Industry 2.0 prompted the rise of assembly lines due to the introduction of oil and electricity, which brought about the emergence of automation in the late 19th century. Telegraphic communication was also invented in this time period.

In the 20th century, the world entered into Industry 3.0, also known as the Information Age. This was the time period when computers, data analytics, cellphones, and the Internet were introduced. It was possible to run a factory without human assistance.

In 2011, the German government started using the term “Industry 4.0” in one of its high-tech strategy forums, but it was only popularized by Klaus Schwab during the World Economic Forum in 2015. In other words, Industry 4.0 is a relatively new phase, leading to a myriad of many ongoing conversations on what constitutes its defining technology. Collectively, most people can agree that Industry 4.0 is an advanced use of the Internet, where technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data, IOT, and advanced robotics can be achieved due to a highly connected cloud environment. It is worth noting that this list continues to grow with additive manufacturing, gene editing, blockchain, and metaverse being added to it, which brings us to the present.

Why should Industry 4.0 matter to designers?

New times, new designer

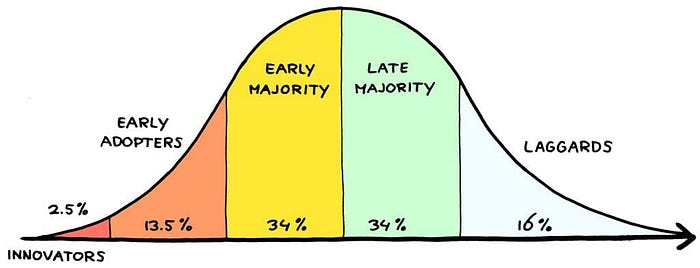

As with every new change, our human brain generates a fight-or-flight response. Designers are at a similar crossroads in terms of deciding whether to embrace new technology or stick with the status quo. Take the diffusion of innovations model by Professor Everett Rogers as a reference. Essentially, there are two extreme groups of people when it comes to adopting technology. The innovators are the first movers, whilst the laggards are those who reject the current paradigm. Hence, not everyone is agreeable with Industry 4.0. More specifically, given its recency, individuals and companies may still persist in their own existing paradigm without seeing the need or impetus to move forward. They may even resist and retaliate against such trends.

Take the battle between Netflix and Blockbuster, for example. At one point, both companies were competing over the same type of customers, despite Blockbuster acting as Goliath with $6 billion in revenue, and a hundred times bigger than Netflix. However, the odds became clearer when Netflix innovated aggressively by changing not only their go-to-market approach but also their business models. Eventually, their underlying success lay in their appreciation of Internet streaming, eventually winning the viewers over through digital means, and ultimately causing Blockbuster to go bankrupt. Netflix embraced digitalisation, whereas Blockbuster was stuck in the previous era.

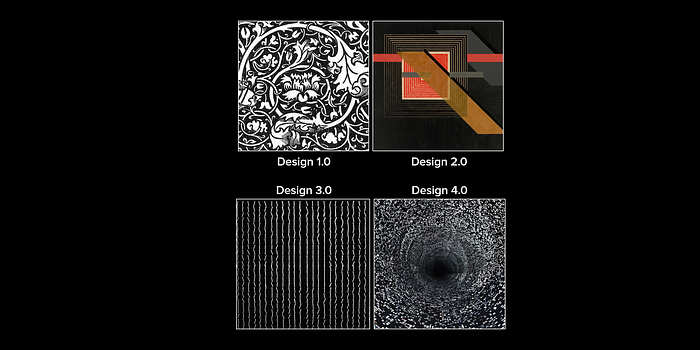

Designers are no different, and interestingly, there are examples of such design groups across the industrial revolutions. In Industry 1.0, there were the designers from the Art & Craft movement, who refuted the use of machinery over craftsmanship. The Art Nouveau designers were the next antagonists to design in Industry 2.0 with their elaborate and ornate works, typically done with skilled craftsmanship. Not all design groups resist change, as can be seen by the Bauhaus. Industry 3.0 was the exodus from hand-drawn plans to computer-aided design (CAD) software when companies like Corel, Autodesk, and Adobe entered the design market. And so the story persists in Industry 4.0, where designers are choosing either to grapple with Industry 4.0, or settle for Industry 3.0’s norm.

Levelling up from Industry 3.0

Yet, the tricky part of Industry 4.0 is the blurring of lines between two phases, as Industry 4.0 rides on its predecessor. With the emergence of the Internet, access to new information has become extremely easy yet fragmented. The upside is more rapid discovery and execution of new ideas. The downside, however, is the expansive sea of innovation, each fighting for its own dominance in a melee of tug-of-wars. Rather than a clean cut of a new industrial revolution, Industry 3.0 and 4.0 are more like a blotch of digital technology. (It could also be due to hindsight bias, where commentators of the present downplay the messiness that actually took place in the past industrial revolutions.)

Designers are thus often faced with the predicament of having mastered a tool or skill, only to realize there is a newer, better tool out there in the market. In the past, designers were expected to both design and code front-end applications. Gone are those days with the rise of Figma and Webflow, as well as many other no-code platforms. If Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator are what distinguish a designer from a non-designer, think again, as new platforms like Canva have entered the preset template market.

Connectivity and automation are two key underlying differentiators between Industry 3.0 and 4.0. Undeniably, artificial intelligence will loom over the UX/UI design community. Uizard, for example, is positioned as a rapid, AI-powered prototyping tool used for designing wireframes, mockups, and prototypes in minutes. Demand is also growing for 3D modelling as cyber-physical environments are becoming a reality with digital twinning and IOT sensors. Would these trends be the new skills for the design world of Industry 4.0?

Cutting across the different paradigm

A common misconception is that technology trends are only applicable to technical people. This may be true for incremental ideas, but let’s not forget the transformative power of an invention that ripples across industries as a movement. There are enough examples across history, ranging from automotive to smartphones, which show the incredible network effect of innovative solutions.

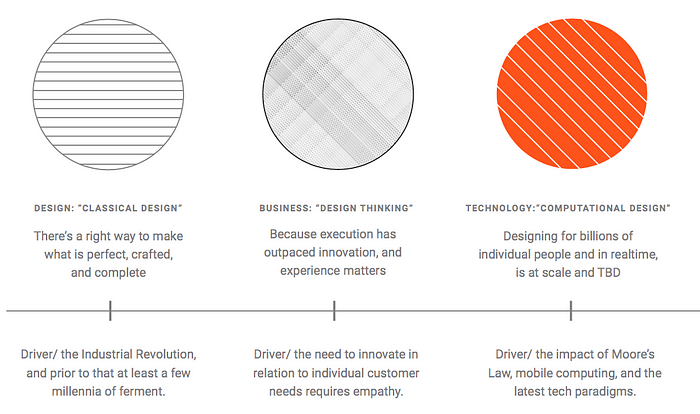

Still, it is tempting to think that Industry 4.0 is only for designers working in tech companies or dealing with digital technology, but this thinking is far from the truth. Perhaps John Maeda best identifies three groups of designers — the classical designers, the business designers, and the computational designers — and how a combination of these designers “will be able to move faster than their competitors.” Guess what the driver behind the classical designer type is? The Industrial Revolution. It is no wonder designers in top companies are progressing because their classically trained designers are also syncing and transiting into Industry 4.0. Consider the industrial designer who now designs with IOT in mind, or the graphic designer who can now dabble in both the physical and virtual worlds through augmented reality. Or the architect that relies on big data to inform the circulation of space. Or the business designer who is defining the interrelationship between the chatbot and a set of diverse users.

Speaking of users, let’s also recognise that they too are part of Industry 4.0. And unlike the users of other industrial revolutions, these users are uniquely positioned to create their own content easily. They are accustomed to speed and rapid change. They are early adopters of mobile technology at an early age and are interoperable across physical and virtual environments.

And from there, we start to see the different vantage points of other users. Users of different languages and colours. Users with special needs. Innovators. Laggards. But beyond end usage, we should consider other important stakeholders that shape and influence design in a given context. If we apply another lens, such as the PESTLE framework, we may uncover the viewpoints of politicians, market leaders (or competitors), communities, regulators, and ethical and environmental bodies. Through the eye of a well, the designer looks up and sees a narrow view of the sky. Only by venturing out of the well would the designer see the entire spread of the horizon.

Design 4.0

At one point, well-known Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan contributed to the modern digital ecosystem based on these words:

“If words were ambiguous and best studied not in terms of their “content” but in terms of their effects in a given context, and if the effects were often subliminal, the same might be true of other human artifacts, the wheel, the printing press, the telegraph, and the TV.”

I often wonder how differently we, as designers, view Industry 4.0 if we had played a little game by switching around the words we attribute our understanding to. What if Industry 4.0 was reframed as Design 4.0 for designers? Retaining the full context of the current world we live and work in, could we rethink our current understanding of design?

4 ways to become Designer4.0

1.Look for design innovators on the fringes.

It can be very tempting to stick with the current design tribe, which is normal, especially when they speak the same language and have the same practices. The danger with such behavior is the repercussions of previous design movements turned into laggards. The alternate approach is to sniff out designers on the fringes. These are people who are actively experimenting. They won’t immediately call themselves designers; they’re more like innovators. And while they may be connected with other designers, they are also having conversations with innovators in other fields. Finding such innovators is hard, but there is a lot to learn once you meet one of them. Your odds may increase when you expose yourself to non-design forums and conferences, and possibly new tribes outside of design.

2. Call into question the Design 3.0 standards.

Just like Netflix, the first step is to recognize the opportunities that lie ahead as designers without dismissing the absurd possibilities. To do this, we have to ask the question, "What does it mean to be a designer?" Such an exercise is a deliberate activity to extract your current worldview and qualms about yourself, which may take time. It does, however, help to provide a reframe of your current reality, if there is one. For example, a designer may start by stating that a designer creates wireframes and beautiful screens, but spells possible obsoletion when AI becomes more sophisticated. A reframe could be the following: a designer explores the complexity of beauty through new media. Although similar, the reframe helps the designer become more nimble in the changing environment. The outcome could range from conversational interfaces, virtual reality or experiential art forms.

3. Be good with what you know, but be better with what you don’t know

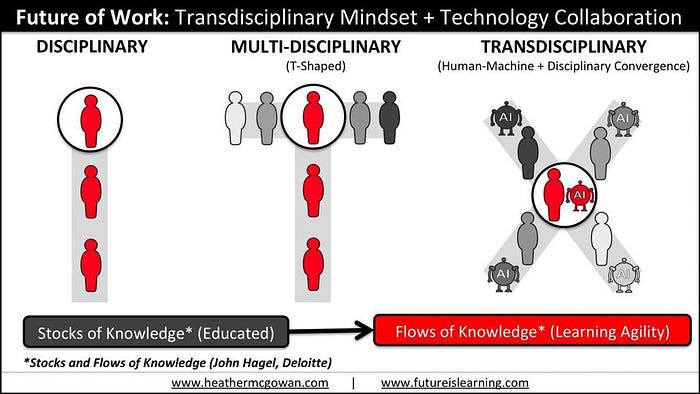

Pick contrasting skills that fit your current role as a designer. It may be counterintuitive, but it is this difference that makes you an ambidextrous designer. For example, if working with 2D mediums such as visual graphics is what you’re good at, how about trying 3D modelling? If you are working in healthcare, what about learning about cybersecurity? And if you are an expert on a subject matter, what about expanding your horizons by striving to be an expert in people management? In an existing paradigm, the T-shaped person is celebrated for having complementary multidisciplinary skills. Transiting to a new paradigm requires X-shaped thinking. This is done by picking two divergent skills and having the intersections in them.

4. Be a scientist: experiment, learn and repeat

In the spirit of experimentation, the person who tests their assumptions rigorously triumphs. Rather than cowering from the challenge, we can learn to embrace and adapt to changing requirements. Instead of being preachers, prosecutors, or politicians, we can be scientists, as described by Adam Grant. The trait of being a scientist is to develop a sense of intellectual humility by treating your current ideas as a hypothesis worth testing continuously.

We often see programming as an endeavour to build an application fit for its intended purpose in an industrialised setting. In the age of Industry 3.0, large clunky computers were costly and housed in research facilities. As a result, early computational work focused on producing utilitarian outcomes. It was through one technologist by the name of Vera Molnar that the hypothesis of computing being a form of artistic expression was formulated. Her work sets the stage for the future of computer art and generative art. It paved the way for the future generation to redefine computer art in Industry 4.0. One such upcoming new media designer is Refik Anadol. Through his exploration of aesthetics and machine intelligence, he has derived a radical art form that exploits the power of artificial intelligence onto a large interactive digital canvas found in architecture. He became a technologist, an artist, and a scientist all at once, possibly a representation of the prototypical Designer 4.0.

Come full circle, Allen’s proclamation of A.I. winning is a distant echo. Surely, whilst new technology can be exploited, or even rejected, it can also be harnessed as a new enlightened form of design. As designers in Industry 4.0, let us remember why we are designers — imagineers of any given medium. The call to become more transdisciplinary is imminent, but as John Maeda concludes,

“Computation is made by us, and we are now collectively responsible for its outcomes.”

Further readings

Roost, Kevin. An A.I.-Generated Picture Won an Art Prize. Artists Aren’t Happy. New York: The New York Times, 2022. Online.

Rogers, Everett. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition. New York: Free Press, 2003. Print.

Maeda, John. Design in Tech Report 2017.Online.

Marchand, Philip. Marshall McLuhan: The Medium and The Messenger : A Biography (Rev Sub ed.). Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1998. Print.

Grant, Adam. Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know.New York: Penguin Publishing Group,2021. Online.

Maeda, John. Why we shouldn’t forget that the world’s first computers were humans.Online.

Lissitzky, El. Proun.Chicago: Art Institute Chicago, 2018. Online.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK