When the Surgeon Was an Uneducated Barber

source link: https://nautil.us/when-the-surgeon-was-an-uneducated-barber-22409/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

When the Surgeon Was an Uneducated Barber

A medical student confronts the history of surgery.

Come here,” the vascular surgeon told me during a lull in activity. I stepped closer. “Put your hand where mine is.” I burrowed my hand into the open abdomen, my wrist sliding past a mess of slippery intestines that occasionally contracted with a wave of peristalsis.

“You feel that?” he asked me. I nodded as a strong, steady pulse pushed against my fingers. “That’s the aorta.”

Over the past few weeks as a medical student on my surgery rotation, I had begun learning many of the tasks essential for a variety of operations. I had practiced suturing wounds closed, tying surgical string to my scrub pants so that I could hone my knot tying skills in between surgeries. I had grown familiar with how each surgeon liked to organize the array of wiring and tubes responsible for inflating the abdomen to improve visibility, vacuuming blood to locate the source of bleeding, and burning tissue to cauterize blood vessels. I had learned how to replace the arms on the behemoth that is the approximately $2 million da Vinci robot frequently used by some of the surgeons at my hospital, marveling at how much money could be put to work in a single room.

Medicine had been based on one man’s anatomical romp through the animal kingdom.

Each little task represented centuries of progress and innovation, the result of countless surgeons and non-surgeons alike driving the field forward. But in that moment, with my hand against the steady thrum of our patient’s heart driving blood down the torso toward the legs, I wasn’t thinking about history but that against my fingers pulsed the vitality of another human being. A person who was placing their full trust in our care. The weight of that responsibility hit me, as it would again and again throughout my rotation on the surgical service. Rarely do we place as much trust in a stranger as we do in the operating theater. How did the profession of surgery progress to this point? In large part, at the expense of the vulnerable.

The essence of the surgeon has changed dramatically, not over three or four thousand years, but only over the last hundred,” Ira Rutkow, surgeon, historian, and author of Empire of the Scalpel, published this March, told me. In his book, Rutkow offers an overview of surgery’s long course from the Stone Age to modern times. Four main advances, he writes, led to the development of modern surgery: an understanding of human anatomy, an ability to control bleeding, a means of controlling pain, and a method of minimizing infection.

Poor outcomes were so prevalent that surgeons—loosely defined as people who used their hands to physically intervene on the human body to treat injuries or disease—“were usually looked at askance,” Rutkow said. The Code of Hammurabi—the legal text of the famed Babylonian ruler who reigned from 1792 to 1750 B.C.—included a warning of the risk of failure in surgery: “If a surgeon has treated a gentleman for a severe wound with a bronze lancet and has caused the gentleman to die, or has opened an abscess of the eye for a gentleman with the bronze lancet and has caused the loss of the gentleman’s eye, one shall cut off his hands.”

Before Andreas Vesalius’ seminal work De humani corporis fabrica (On the fabric of the human body) was published in 1543, common understanding of anatomy in Europe was largely based on the work of a physician named Galen of Pergamon, who was born in what is now Turkey in 129 A.D. Because dissections of human bodies were forbidden in the Roman Empire at the time, Galen relied on dissections of animals to make inferences about humans. His teachings included descriptions of the liver as having five lobes (human livers have two) and the wall separating the left and right sides of the heart as being littered with small holes (which led to significant misunderstandings of human circulation until the 17th century). “Western anatomy and medicine had, for hundreds of years, been effectively based on one man’s anatomical romp through the animal kingdom,” writes Paul Craddock, historian and author of Spare Parts: An Unexpected History of Transplants, published this May.

In contrast to the precedent of scholars blindly trusting Galen’s observations, Vesalius performed his own dissections and noted how his findings differed from those of the esteemed Galen. His descriptions in the Fabrica helped usher in a wave of questioning and experimentation emblematic of the Scientific Revolution. It would not be long before Rutkow’s second criterion for the development of modern surgery—the ability to stop bleeding—was met.

“The surgeon’s role fell mostly to uneducated barbers who had been frequenting monasteries since the late 11th century AD, when beards were banned,” Rutkow writes. The two fields became more intertwined as barbers took on more surgical roles, like performing bloodletting and amputating digits. Patients’ pain was often understood as having a biologically protective role, or even as a religious blessing.

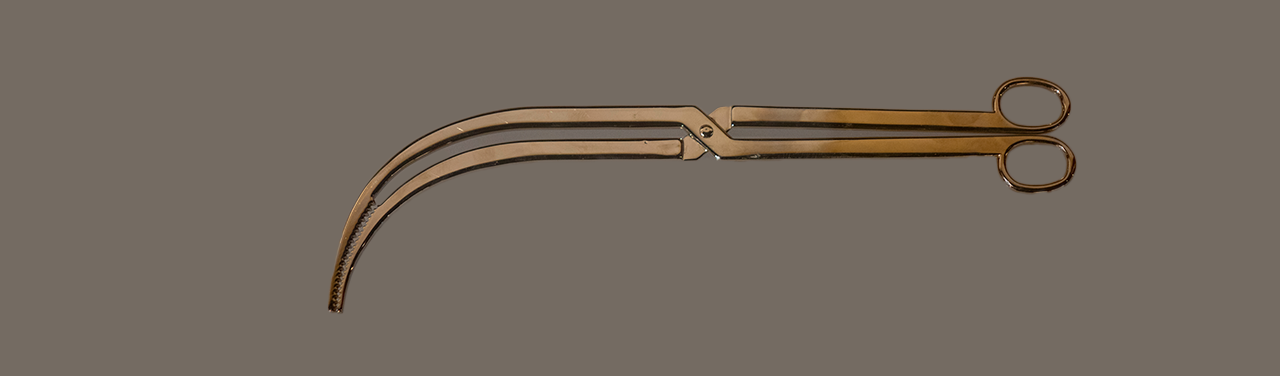

Shortly after the Fabrica’s publication, during the Italian War of 1551-1559, one such barber-surgeon named Ambroise Paré struggled to find a method to halt bleeding in amputations. Based on the Greek and Roman use of ligatures to tie off blood vessels—a practice that by this time had been abandoned—Paré developed an instrument called the bec de corbin (crow’s beak) to close off large blood vessels, buying time for a ligature to be tied around the blood vessels, stopping the hemorrhage. This device would evolve into today’s hemostat, a surgical clamp used in almost every surgery I’ve participated in—an essential in the modern operating room.

The surgeon asked his assistants “to unfasten their trousers and relieve themselves in the patient’s open abdomen.”

Lives were sometimes abused and sacrificed without choice in the pursuit of surgical knowledge. Rutkow describes one such instance in 17th-century France. To prepare himself for a surgical reparation of King Louis XIV’s anal fistula—an abnormal tunnel extending from the rectum to the skin around the anus, usually caused by an unchecked infection—the king’s chief surgeon, named Charles-François Félix, practiced his technique on dozens of indigent patients, many of whom died. The success of the operation on the French king in 1686 brought Félix wealth and acclaim, lending prestige to the art of the surgery and jumpstarting a wave of medical tourism to Paris for anal fistula treatment, even for some patients who had no such problem.

Surgery in the United States shares this checkered past. In the 1840s Alabama physician James Marion Sims garnered national attention after publishing his work on vesicovaginal fistula repair, techniques which he optimized through his experiments on enslaved Black women.

It’s almost unfathomable that centuries of surgery passed before the first public use of surgical anesthesia occurred at Massachusetts General Hospital in 1846. Inspired by a public display of nitrous oxide (also known as laughing gas) in which a participant injured himself but was seemingly nonplussed until the gas’s effects wore off, dentist Horace Wells imagined the gas’s potential application for tooth extraction. Collaborations with dentist William Thomas Green Morton, physician Charles Jackson, and surgeon John Collins Warren eventually led to a successfully painless 25-minute neck operation by Warren. Fights later ensued between Morton, Jackson, and Wells as to who should receive credit for the discovery of surgical anesthesia, as well as the associated financial rewards. Although rivalries, spiritual beliefs, and fears about safety limited the speed of its initial uptake, over the next decade surgical anesthesia became widespread.

As surgeries increased in complexity, the need to address risk of infection became ever more dire. Likely due to a belief in the antiseptic power of urine, an early transplant surgeon named Leonardo Fioravanti requested his assistants and spectators of the spleen operation “to unfasten their trousers and relieve themselves in the patient’s open abdomen,” Craddock relates.

Following his groundbreaking research on bacteria that refuted traditional notions of spontaneous generation, French chemist Louis Pasteur conjectured that microorganisms might be a cause of human disease. English surgeon Joseph Lister built on Pasteur’s work to conclude that microbes from the environment—including the millions of bacteria on surgeon’s hands and instruments—seeded wounds, leading to infection. In 1867, Lister published research describing his use of carbolic acid as a means of killing these organisms. His research was met with skepticism but would become universally accepted, heralding a new age of surgery into the 20th century.

Surgery, I learned, owes much of its current practice to fields outside of medicine. Grafting, for instance, taking tissue from one part of the body to heal another part, emerged from agricultural methods. The skin grafting technique described in the Sushruta Samhita in ancient India and the grafting technique described later in the Renaissance, in the 16th century, are both direct transpositions of farming. “That’s where you get phrases like ‘agriculture of the body’ and ‘the farming of men’, all these metaphors,” Craddock told me. “That kind of agricultural frame lies completely outside of legitimate medicine at the time, the medicine of Galen.”

In the early 17th century, the English physician William Harvey discovered the heart’s role as a pump. As a result, Craddock said, “you start to get these mechanical metaphors that speak to a very different understanding of the body as partly machine.”

This mechanical framework, Craddock argues, later shifted to one of craft- or fabric-making as surgeons began using finer techniques on more delicate tissues. French surgeon Alexis Carrel pioneered techniques for suturing blood vessels, allowing for vessels to be reconnected to one another, a critical development in the history of transplant surgery for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1912. According to Craddock, Carrel obtained both suturing material and sewing technique from famous Lyon embroiderer Marie-Anne Leroudier. This inter-industry transfer of skills allowed him to learn how to sew hundreds of stitches into delicate cigarette paper while studying “how far he could push his materials and how the fabric of the human body would respond to the action of his nimble, sensitive fingers,” writes Craddock. Notably, Carrel would later retire to France in pursuit of a eugenics program that, thankfully, never panned out. Yet his technical advances remained of lasting impact to the field of surgery.

A strong, steady pulse pushed against my fingers. “That’s the aorta,” my professor said.

“If the study of surgical history offers any lesson,” writes Rutkow in Empire of the Scalpel, “it is that progress can always be expected, at least relative to the technology of a given era, and will lead to increasingly sophisticated surgical operations with better results.”

The development of military technology has spurred surgical innovations, often by creating new, more gruesome methods of injuring other humans. From the moment “the first machine gun rang out over the Western Front, one thing was clear,” writes historian Lindsey Fitzharris in The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeon’s Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I, published this June. “Europe’s military technology had wildly surpassed its medical capabilities.”

“Shells and mortar bombs exploded with a force that flung men around the battlefield like rag dolls,” Fitzharris writes. “Noses were blown off, jaws were shattered, tongues were torn out, and eyeballs were dislodged. In some cases, entire faces were obliterated.” Men suffering some form of facial trauma from France, Germany, and Britain alone totaled around 280,000 before the war ended.

The Facemaker describes the advancements of British facial reconstruction surgeon Harold Gillies in his efforts to repair the extensive injuries incurred by soldiers during the war. By establishing a center devoted to the interdisciplinary reconstruction of soldiers’ faces—involving teams of “surgeons, physicians, dentists, radiologists, artists, sculptors, mask-makers, and photographers”—Gillies helped pioneer many techniques that would prove critical to the development of plastic surgery. Among these included the use of surgical flaps, healthy tissue cut from one area of the body and then moved to another while maintaining its original blood supply.

It can’t be emphasized enough how transformative some of these surgeries were for these injured soldiers. Gillies’s consideration of both function and aesthetics allowed many of his patients to return to some semblance of normalcy. That alone often proved to be transformative for these injured soldiers. Soldiers with significant facial wounds generally faced considerable obstacles on returning home, including broken engagements, scared children, and lost identities.

In reality there is no way to separate present-day surgery and one’s own practice from the experiences of all the surgeons and all the years that have passed,” Rutkow writes.

I would like to think that, as a medical trainee, I am participating in a long lineage of surgeons, extending from clinicians expanding the definition of who can practice surgery today all the way back to the unnamed Stone Age practitioners who engaged in neurosurgery—as evidenced by numerous skulls with man-made holes scattered around the world. It makes me wonder how the ways we gain knowledge might inform surgical practice, as well as how advances should be memorialized.

Shortly after I palpated the aorta, I assisted with closing the footlong incision in the patient’s abdomen. Because I had been practicing, I was more confident than I had been mere weeks before. I drove the needle into the patient’s skin, my eyes homing in on the line dividing the layers of epidermis and dermis, my target. A fellow watched over my shoulder as I extended the continuous suture down the patient’s belly, trying to close the layers of skin as evenly as possible, avoiding any unnatural ripples or mismatched edges. ![]()

Michael Denham is a medical student at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Lead image: Scarc / Shutterstock

Get the Nautilus newsletter

The newest and most popular articles delivered right to your inbox!

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK