Striping A Disk Drive The 1970 Way

source link: https://hackaday.com/2022/05/16/striping-a-disk-drive-the-1970-way/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Striping A Disk Drive The 1970 Way

These days, mass storage for computers is pretty simple. It either uses a rotating disk or else it is solid state. There are a few holdouts using tape, too, but compared to how much there used to be, tape is all but dead. But it wasn’t that long ago that there were many kinds of mass storage. Tapes, disks, drums, punched cards, paper tape, and even stranger things. Perhaps none were quite so strange though as the IBM 2321 Data Cell drive — something IBM internally called MARS.

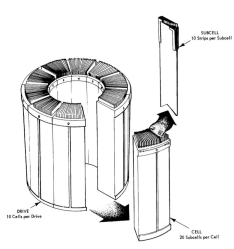

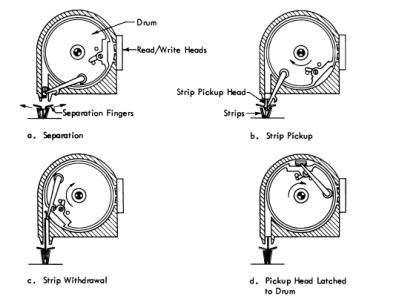

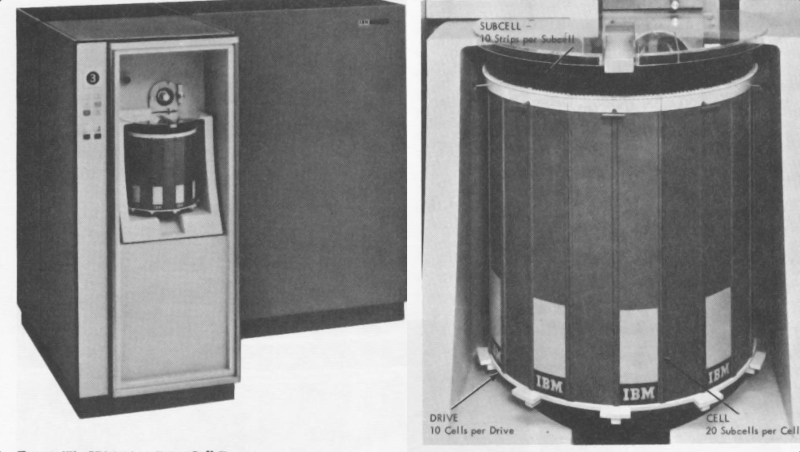

What is a data cell you might ask? A data cell was a mass storage device from IBM in 1964 that could store about 400 megabytes using magnetic strips that looked something like about a foot of photographic film. The strips resided inside a drum that could rotate. When you needed a record, the drum would rotate the strip you needed to the working part and an automated process would remove the strip in question, wrap it around a read/write head and then put it back when it was done.

Needless to say, these didn’t catch on. Tape drives were fine for most things and disk drives would soon be cheaper, dooming the 2321 to be a historical curiosity.

Given the limitations of the day, though, the solution was clever. Each strip was a bit more than two inches wide and 13 inches long. There were 200 strips on each drum and a 20-track head that could move to one of five positions, meaning each strip held 100 tracks of data. For high storage needs, you could connect multiple devices together.

The drum was like a very tall slide projector carrying magnetic strips instead of optical slides

It is hard to see how 200 strips fit in the drum if you look at the pictures. You have to look at the drawing from the IBM manual that makes it clear. The drum is really made up of 10 cells. Each cell has two subcells of 10 strips. The physical arrangement is like an old carousel slide projector. The strips are like very thin slices of pie and the machine sucks one particular strip into a fixed read write head.

Sure, it seems like a bit of a Rube Goldberg, but consider this. A similar IBM disk drive from the day held less than 1/50th of what the data cell could hold. If you loaded a control unit with eight drums, it would be the same as over 440 IBM2311 disk drives. Don’t forget, you’d need upwards of 50 controllers for the disk drives, too. The disk drives, of course, were faster, but not by a lot. The 2311 had an access time of 85 mS as opposed to the data cell clocking in at about 600 mS worst-case although if the stars and the strips aligned it could be as fast as 95 mS.

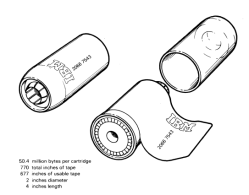

Tape cartridge for the IBM 3850

Tape cartridge for the IBM 3850

If you think these were noisy, you are right. They also took a special oil to lubricate all the workings. Apparently [Nerding] had a chance to work with one of these back in the day. The computer was granting and denying credit authorization and it kept getting hung up. It turned out that sharing these data cells was risky. One program would move the drum and another program would move it again before the first one could read if the programs were accessing opposite sides of the drum.

IBM also produced the 3850 that could store up to 472 GB on the IBM System/370. This was a very similar idea, but the magnetic tape was not in strips but in small cartridges that held about 50 MB each. This was more like an automated tape machine than a disk drive, though, but it still shows that disks took a while to completely overtake tape.

IBM’s diagram of the read/write head

We have a mild urge to build a working replica. Sure, there’s some precision involved in lining up on 1.8 degrees but that number sure has a familiar ring to it if you build 3D printers or CNC machines. A typical stepper motor just happens to make 200 full steps per revolution. Go figure. The other thing that would be hard to do accurately is handling that flimsy film. The film itself is, according to IBM, 0.005 inches thick. Still, you’d think you could figure something out.

We’d settle for an emulator, especially if it had a graphical simulation. While we may have IBM to thank for popularizing tape storage, we can thank Bing Crosby for making audiotape a thing.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK