Frantic Puppy Protagonists

source link: https://ginadenny.medium.com/frantic-puppy-protagonists-2f50773d979b

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Frantic Puppy Protagonists

They’re adorable and you love them, but do they ever do anything useful?

In the summer of 2021, I read a very popular YA fantasy. Very popular — more than 750,000 ratings on Goodreads and more than 12,000 Amazon reviews. It enjoys a 4+ star rating on both sites. It was a few years old, but it was one of those I kept meaning to pick up, so when I finally got around to it, I was pretty excited to read it.

About halfway through, though, I realized the protagonist hadn’t … done anything. She had been kidnapped (more or less) and had watched a lot of terrible things happen. She had shouted her disapproval and tried to escape, but she hadn’t changed the course of events in the book. She was there, she had front-row seats for all the action, but that was it.

This was odd, so I started to really look more closely through the second half of the book. I really wanted to see the moment where all this helplessness turned into action, when her hidden talents leapt out onto centerstage to prove that she was the right person to be at the center of this story.

No such luck.

By the end of the book, the bad guys had triumphed mostly, and the foothold the good guys had was thanks to someone else, not the protagonist. She was a bystander for the whole thing.

She did a lot of stuff. She punched some people, just to be put back in handcuffs. She shouted at people, just for them to not listen to her. She ran away, just to be dragged back. She watched as atrocities happened. She bemoaned the atrocities in her inner dialog.

But none of it mattered.

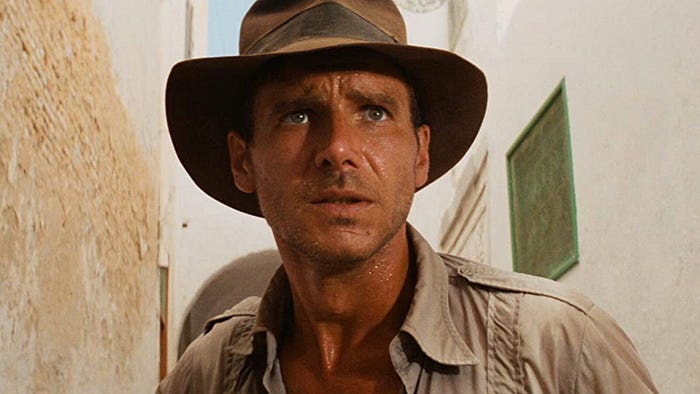

Big Bang Theory and Indiana Jones

You might be thinking, “That’s crazy talk, there would never be a protagonist in a big-budget book who doesn’t do anything! That’s bush-league stuff!” This concept, though, was memorialized in an episode of The Big Bang Theory, in which Amy points out that Indiana Jones is superfluous to his own movie. This was not the first time someone pointed it out, but it was the first time this fact was put in front of a mainstream audience on a large scale.

And it’s true: Indiana Jones does a lot of stuff in Raiders of the Lost Ark. He shoots, he runs, he jumps on cars, he’s ruggedly handsome and charming, he dodges arrows and slingshots, he gets the girl.

But none of it mattered.

Indiana watches the Ark get opened by Nazis, he doesn’t cause it to happen, he doesn’t stop it from happening, he doesn’t actually get involved, other than to attempt to slow everyone down a bit during the second act.

(if you want to lol and roll your eyes at a dudebro insisting that Raiders is actually a quiet character study and “you all just don’t get it” you can read this article on Collider)

The Sexy Lamp Test

When I first finished this very popular YA fantasy, I complained to a few friends* that it failed the Sexy Lamp Test, but that didn’t feel completely accurate.

*by “a few friends” I definitely mean a few thousand people on twitter

The Sexy Lamp Test is a critique theory first put forth by comic book writer Kelly Sue DeConnick. In her words: “If you can take out a female character and replace her with a sexy lamp, YOU’RE A FUCKING HACK.”

So, if your female character sits on a couch and listens to the hero talk, gets carried to bed by the hero, gets carried out of the room by her abductor, sits on the floor with her hands tied (and her skirt artfully torn up her thigh, of course), watches the hero fight for her honor, and then gets carried off into the sunset by the hero… she’s a lamp. A sexy lamp, but still a lamp.

This was what I thought this popular YA fantasy book was: a sexy lamp book. But, as I said, that didn’t feel quite right.

You see, the protagonist did stuff. She tried to run away, she shouted her opinions, she interacted with bad guys and good guys. It’s just that nothing she did mattered to the plot.

Seeing the Pattern Elsewhere

Then in late 2021, I read another YA fantasy that did the same thing. The male protagonist did a bunch of stuff. He got into fights. He made mistakes. But at the end of the book, he was literally right back where he started, having accepted his lot in life.

All his fighting and flailing around had failed to change the plot of the story, had failed to change his own trajectory.

If this was book one in a series, that could make sense, I guess, especially if the author is well-established. A well-established author has bought a lot of trust with the audience. We know they will deliver a good story, we just need to trust them. Book one in a series might not do what we expected, but we can reasonably expect the rest of the series to fulfill its promises.

This YA fantasy was a standalone, though. And the previous example I gave was the start of a series, but it was by a debut novelist who hadn’t bought any trust with the audience yet.

Then it happened again. Another YA fantasy (my favorite genre, if you can’t tell by now), but this time the protagonist accomplished nothing in a slightly different way.

Actively Inactive

This protagonist had magic powers and was living in turbulent times. She is recruited to use her powers to stop the progression of evil, she met a boy who was on the side of evil, and she waffles about whether or not she will help the good guys or the bad guys.

Pretty standard YA fantasy stuff, in other words.

The problem is that with all her waffling, she ended up literally back in the same place she was at the beginning. She used her powers to help the good guys, got cold feet, used her powers to undo the help, then stood by and did nothing as the bad guys won. She didn’t end up with the boy who made her waffle in the first place, it wasn’t a romance, and she didn’t seem to have learned anything along the way.

She just . . . didn’t stop evil.

It wasn’t even that she tried and failed, which is an important part of any long-form fiction. It wasn’t that she made a huge mistake and had to undo it. She just changed her mind, put everything back the way it was, and let the chips fall where they would have fallen without her intervention.

This is when it clicked into place for me.

That first book I’d read, the one that I thought was a sexy lamp book, the mega bestseller? It wasn’t a sexy lamp book.

Photo by Amber Aquart on Unsplash

It was a Frantic Puppy Protagonist Book

A Frantic Puppy Protagonist (hereinafter “FPP”) is a protagonist who is extremely likable or charismatic. They might be hilarious or ultra-competent. They can be smart and have awesome magic powers. They can be super badass warriors or interestingly quirky folks.

You want to read about them, in other words. You want to follow their story, you root for them to win all along the way. This is crucial to identifying a FPP. If they aren’t intensely likable, then no one gets fooled into reading the entire book.

A FPP do a lot of stuff. Like… a lotof stuff. Every scene has stuff going on. They fight, they negotiate, they make jokes, they make decisions. This is also crucial in identifying a FPP. If they aren’t doing anything, it’s a very boring story. If they aren’t doing anything at all, they likely aren’t the protagonist. Or it’s possible you’re reading a very quiet novel where all the stakes are internal and the “action” is more about decisions and feelings, rather than actual actions. Those novels have their place in the world, and if you love them, I want you to enjoy them exactly as they are. Those are not what I’m talking about here.

FPPs are named after puppies who get the zoomies. They run in circles, they bark, they jump, they fetch things just to drop them immediately, and then at the end of their little zoomie session, they just lay down and act like nothing happened.

In the grand scheme of things, nothing did happen. They ran around the yard or the living room and nothing changed. They still lived in the same place, with the same people, and would wake up to the same routine tomorrow morning.

What To Do With This Information

Once I identified this issue in published books, it was a lot easier to see it happening somewhere else: pre-published books.

If you’re a writer, then you are reading a lot of pre-published books. Giving and receiving feedback is absolutely imperative for any writer and swapping manuscripts with your writing group and critique partners is the best way to do that. So, you end up reading a lot of books that aren’t ready yet.

If you’re a writer, then you’ve got at least a couple books that aren’t ready to be published yet.

This is why it’s helpful to be able to identify a FPP. If you have a FPP, and your book is pre-published, you can still fix it. The chances that you’re going to be the one in a million that gets to be a bestseller with a FPP is… well… one in a million.

Here’s two simple steps to avoid a FPP:

- Compare your protagonist’s starting point to their endpoint.

- Track your protagonist’s actions and how they affect the plot.

Compare Your Protagonist’s Starting Point to Their Endpoint

Ask yourself a few questions: Why are you telling this story? Why have you chosen this protagonist? If your protagonist doesn’t affect the plot, then why are they your protagonist?

The protagonist is the one who changes, either themselves or the world. The protagonist has a goal and works toward it. Luke Skywalker wants to get off that dirty, boring planet. Harry Potter wants a family that loves him. Cady Heron wants to be accepted by her new public school peers. Lightning McQueen wants to win the big race. Cinderella wants to be free of her tyrannical stepmother. Rory Gilmore wants to go to Harvard and be a journalist. Steve Rogers wants to save innocent people.

Their goals can change over the course of the story. Luke and Harry learn about a massive evil in the world and decide to defeat it. Lightning McQueen learns that friendship and family is more important than winning. Rory decides Yale is better for her than Harvard.

However, in changing their goal, they do not revert back to who they were before. Luke and Harry don’t see the evil in the world and decide they’re too scared to fight and go back home to hide in obscurity. Rory doesn’t decide to skip college altogether and stay in Stars Hollow.

If your protagonist’s endpoint is exactly the same as their starting point, you might have a FPP.

The exception to this is that your character always wanted to stay the same, but the inciting incident of your story forced them to fight for that stability. In that case, though, your protagonist is still working toward a goal, and their actions should affect whether or not they reach their goal.

Track Your Protagonist’s Actions and How They Affect the Plot

In each scene, you’ve got forward momentum, things happening that push the plot forward.

Look at your protagonist’s role in every scene, even if they aren’t on the page. What are they doing and how does their action affect the plot?

They’re likely doing stuff in every scene. Making decisions, talking to other characters, moving around within the world you’ve built.

But if that stuff doesn’t have any effect on the plot, if those conversations just put your character back where they started, you might have a FPP.

Follow me on Twitter for education, feminism, and writing. Consider upgrading to a paid Medium account to read everything behind the paywall. Your subscription really helps me as well as this publication.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK