1

Travel on airless worlds

source link: http://hopsblog-hop.blogspot.com/2014/06/travel-on-airless-worlds.html

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Travel on airless worlds

When we get to other worlds how will we get from point A to B? There are no roads on Ceres. No rivers or oceans on the moon. No airports on Enceladus or even air for an airplane to glide on.

Until transportation infrastructure is built, suborbital hops seem the way to go. A suborbital hop is an ellipse with a focus at the body center. But with much of the ellipse below surface.For a suborbital hop from A to B, how much velocity is needed? At what angle should we leave the body's surface? At what angle and velocity do we return?

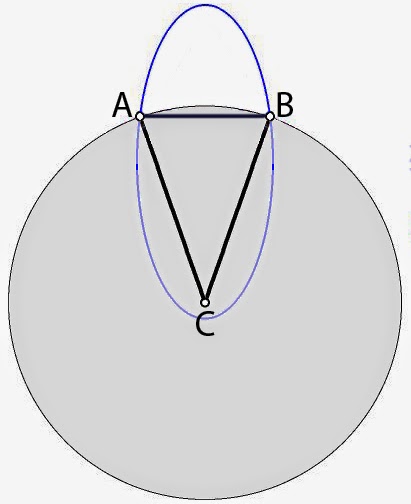

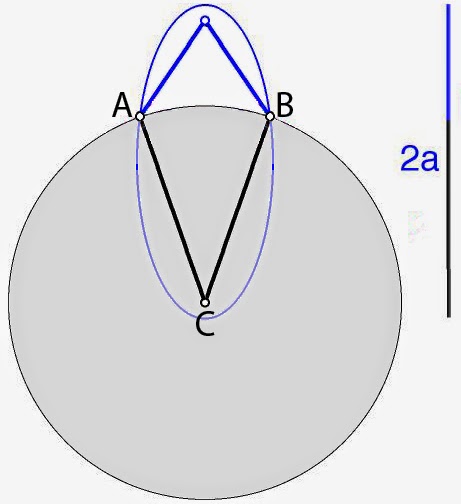

Points A and B are two points in a Lambert Space Triangle. The triangle's third point C is the body's center. Two of the sides are radii of a spherical body so the triangle is isosceles. A point's distance from one focus plus distance to second focus is a constant, 2a. 2a is the ellipse's major axis. Since A and B are equidistant to the first focus, they're also equidistant to the second focus. Points A & B, the planet and ellipse are all symmetric about the ellipse's axis.

The payload returns to the body at the same angle and velocity it left.

There are a multitude of ellipses whose focus lies at the center and pass through points A and B. How do we find the ellipse that requires the least delta V?

Specific orbital energy is denoted ε.

ε = 1/2 v2 - μ/r.

1/2 v2 is the specific kinetic energy from the body's motion. - μ/r is the specific potential energy that comes from the object's distance from C, the body's center. For an elliptic orbit, | - μ/r | is greater than 1/2 v2, that is the potential energy overwhelms the kinetic energy. If potential and kinetic energy exactly cancel, the orbit is parabolic and the payload's moving escape velocity.

So to minimize 1/2 v2 we'd want to maximize | ε |.

It so happens that

ε = - μ/(2 a).

To grow |- μ/(2 a)| we shrink 2a. So we're going for the ellipse with the shortest possible major axis. The foci of all these ellipses lie on the same line. Moving the focus up and down this line, it can be seen the ellipse having the shortest major axis has a focus lying at the center of the chord connecting A and B. That would be the red ellipse pictured above. The angle separating A and B is labeled θ. Recall the black length and red length sum to 2a

2a = r + r sin(θ/2).

a = r(1 + sin(θ/2))/2.

Now that we know a, we can find velocity with the vis-viva equation:

V = sqrt(μ(2/r - 1/a)).

At what angle should we fire the payload?

It's known a light beam sent from one focus would be reflected to the second focus with the angle of incidence equal to the angle of reflection: Angle between position vector and velocity vector is (3π - θ)/4. A horizontal velocity vector has angle π/2 from the position vector.

(3π - θ)/4 - π/2 = (3π - θ)/4 - 2π/4 =

(π - θ)/4

(π - θ)/4 is the flight path angle departing from point A. If A and B are separated by 180º (i.e. travel from north pole to south pole), flight path angle is 0º and the payload is fired horizontally. If A and B are separated by 90º (i. e. travel from the north pole to a location on the equator), flight path angle is (180º - 90º)/4 which is 22.5º

When A and B are very close, θ is close to 0. (180-0)/4 is 45º. When A and B are close the the payload would be fire at nearly 45º. With one focus near to the surface and the other at the body center, the ellipse would have an eccentricity of almost 1. The trajectory would look parabolic.

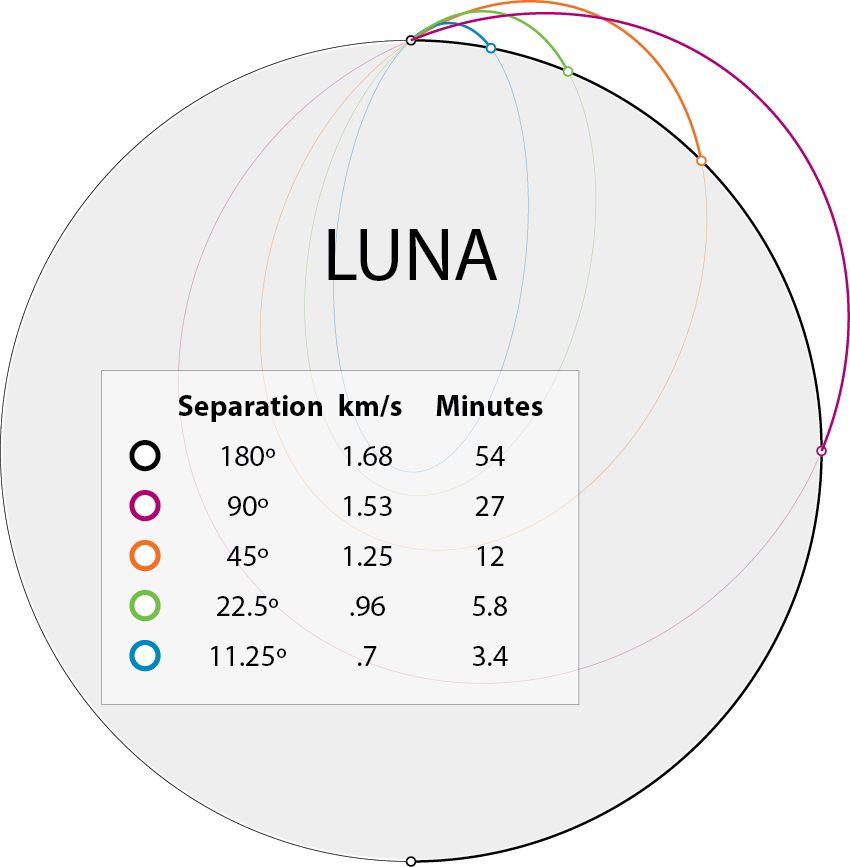

Here's a few possible suborbital hops on our moon: Minimum energy ellipse from pole to pole is a circle. Launch velocity is about 1.7 km/s. It'd take the same amount of delta V for a soft landing at the destination. Trip time would be about 54 minutes

From the north pole to the equator would take a 1.53 km/s launch. Trip time would be about 27 minutes.

Period of a circular orbit (T) is 2 π * sqrt(r3/(Gm)) where m is mass of planet.

Mass can be expressed as ρ * volume where ρ is density.

2 π * sqrt(r3/Gm) = 2 π * sqrt(r3/(G * 4/3 *π * r3 * ρ).

The r3 cancels out and we're left with T = sqrt(π/(G * 4/3 *ρ).

Thus trip times for a given separation rely solely on density. Period scales with inverse square root of density.

I did a spreadsheet where the user can enter angular separation on various airless bodies in our solar system. Delta Vs vary widely depending on size of the bodies. But trip times between comparable angular separations are roughly the same. This is because most the bodies have roughly the same density. Denser bodies like Mercury will have shorter trip times while icey, low density bodies will have longer trip times.

I got some help on this from a Nasa Spaceflight thread. My thanks to AlanSE and Proponent.

After time we would establish infrastructure on bodies and burrow into their volume. With tunnels we could reach various destinations with very little energy. I look at this in Travel On Airless World Part II.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK