Does Signal’s “secure value recovery” really work?

source link: https://palant.info/2020/06/16/does-signals-secure-value-recovery-really-work/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Does Signal’s “secure value recovery” really work?

If you care about privacy, Signal messenger is currently the gold standard of how messenger services should be build. It provides strong end-to-end encryption, without requiring any effort on the user’s side. It gives users an easy way to validate connection integrity via another channel. Its source code is available for anybody to inspect, and it’s generally well-regarded by experts.

The strong commitment to privacy comes with some usability downsides. One particularly important one was the lack of a cloud backup – if you ever lost your phone, all your messages would be gone. The reason is obviously that it’s hard to secure this sensitive data on an untrusted server. That isn’t an issue that other apps care about, these will simply upload the data to their server unencrypted and require you to trust them. Signal is expected to do better, and they finally announced a secure way to implement this feature.

Their approach is based on something they call “secure value recovery” and relies on a PIN that is required to access data. As the PIN is only known to you, nobody else (including administrators of Signal infrastructure) should be able to access your data. This sounds great, in theory. But does that approach also work in practice?

The trouble with short passwords

One part of the announcement caught my eye immediately:

Signal PINs are at least 4 digits, but they can also be longer or alphanumeric if you prefer.

Don’t get me wrong, I understand that nobody likes entering lengthy passwords on a mobile device. But this sentence is suggesting that 4 digits provide sufficient security, so a considerable number of Signal users won’t bother choosing a more complex password. Is that really a sensible recommendation?

The trouble is, it’s impossible to properly protect encrypted data with such short passwords. Even if a very slow key derivation algorithm like Argon2 is used and it takes 5 seconds to validate a password (this is a delay which is already considered way too high for usability reasons), how long would it take somebody to try all the 10,000 possible combinations?

5 seconds times 10,000 gives us 50,000 seconds, in other words 13 hours 53 minutes. And that’s assuming that the process cannot be sped up, e.g. because infrastructure administrators can run it on powerful hardware rather than a smartphone. Also, that’s the worst-case scenario, on average it will take only half of that time to get to the right PIN.

Rate limiting to the rescue

So how come in some scenarios a four digit PIN is considered “good enough”? Nobody worries about their credit card PIN being too short. And for unlocking an iPhone it was even considered too secure, so now you can use your thumb’s fingerprint as a less secure but more convenient alternative.

The solution here is rate limiting. Your bank won’t just let anybody try out thousands of PINs, after three failed attempts your card will be blocked. It’s the same with an iPhone: each failed attempt will require attackers to wait before the next try, with the delay times increasing with each attempt: 1 minute after the 5th, 5 minutes after the 6th. After the 10th failed attempt an iPhone might even delete all its data permanently if configured accordingly.

The weakness of these schemes is: they require a party to do the rate limiting, and you will have to trust it. You trust a bank to block the credit card after too many failed attempts, yet banks have been hacked in the past (granted, you would have bigger issues then). You trust the iPhone software to slow down PIN guessing, yet various vulnerabilities allowed FBI to circumvent this protection.

So if Signal simply did rate limiting on their server, we would have to trust administrators of this server and well as the hosting provider to always uphold the rate limiting mechanism. We would have to trust them to keep this server secure, so that no hackers could circumvent the limitations. Essentially, not much would be gained compared to simply uploading data in plain text.

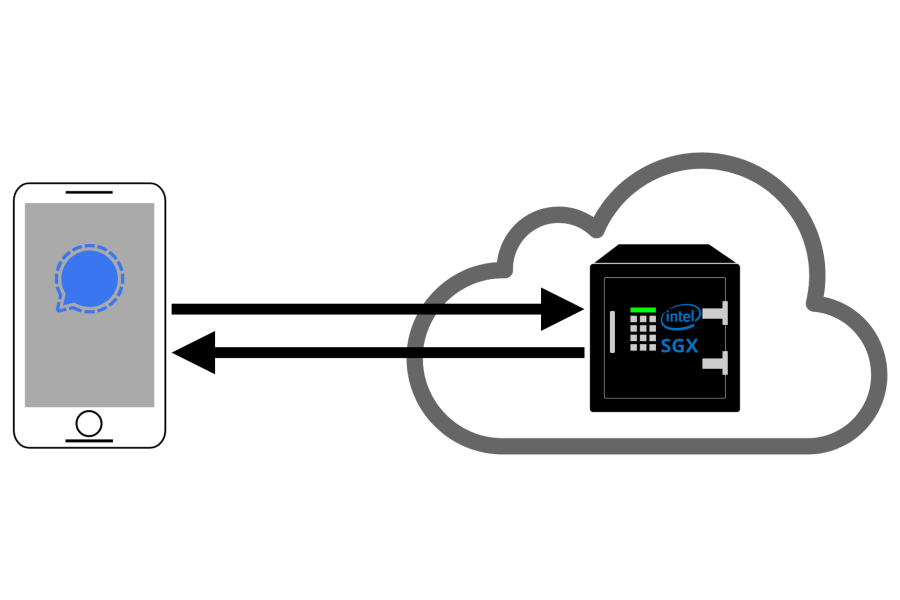

SGX ex machina

In order to change that, Signal pulls an interesting trick: they are going to use a technology built into Intel processors called Software Guard Extensions (SGX). The goal of SGX is allowing “secure enclaves” to be trusted even when the operating system or any other software running on it isn’t, these being encrypted and out of reach for outside code. Enclave validation guarantees that only the expected software is being executed there. The client can then establish a secure connection to the enclave and the magic can unfold.

I am new to SGX myself and I don’t claim to understand all the crypto behind them. But enclave validation is a signature, and that signature requires a private key. Where does that key come from and how is it being trusted? Apparently, the enclave contains an attestation key which is signed by Intel. And here we have one potential attack point.

Shifting the root of trust

One of the concerns is that Signal is a US organization. So if you are somebody who touches US interests in their communication (and US have very wide interests), the US government could order Signal to provide your messages. Which luckily they cannot, thanks to end-to-end encryption.

But now the US government could go to Intel, which also happens to be based in the US, and ask them to sign keys for a malicious enclave. That malicious enclave could then get into the data replication process and thus extract all the secrets. No more rate limiting, decrypting data with simple passwords is easy and very fast.

Note: Once again, I’m not an SGX expert, and I could be wrong about the above. It would be great to have somebody confirm or deny my conclusion here.

Attacks on hardware

There are also simpler ways to attack secure enclaves however. Somebody with access to Signal infrastructure, be it Signal admins, US government or some hackers, can run any code on the servers where the secure enclaves are located. In theory, this shouldn’t matter due to the enclaves being properly isolated. In reality, a number of attacks against SGX have been publicized over the years.

There is for example the SGAxe attack which was published just recently:

We then proceed to show an extraction of SGX private attestation keys from within SGX’s quoting enclave, as compiled and signed by Intel. With these keys in hand, we are able to sign fake attestation quotes, just as if these have initiated from trusted and genuine SGX enclaves.

Ok, so Intel is no longer required to sign a malicious enclave, anybody can do that. And that’s merely the most recent example. Earlier this year it was Load Value Injection:

we smuggle — “inject” — the attacker’s data through hidden processor buffers into a victim program and hijack transient execution to acquire sensitive information, such as the victim’s fingerprints or passwords.

Yes, compromising the code running inside a secure enclave is also a way to extract all the secrets. Late last year it was PlunderVolt:

We were able to corrupt the integrity of Intel SGX on Intel Core processors by controling the voltage when executing enclave computations. This means that even Intel SGX’s memory encryption/authentication technology cannot protect against Plundervolt.

The list goes on, prompting a journalist to write on Twitter:

I believe SGX is a conspiracy by PhD students and infosec researchers doing hardware-based attacks. It has barely any real use case, but so many papers can be written about attacking it.

I am inclined to agree. Even if all of these vulnerabilities are patched quickly (via firmware updates, code changes or even new hardware), each of them provides a window of opportunity to extract data from secure enclaves. Does it make sense to build products on top of a foundation that is only trustworthy in theory?

The question of transparency

Either way, all of this only matters if we (the users) can verify that Signal’s secure enclaves work exactly as advertised. Meaning: the values required to decrypt the data will only be provided to the rightful owner, without any backdoors to circumvent the rate limiting mechanism. As long as this cannot be verified, we are back to trusting Signal.

At the moment, I can only see underdocumented client-side SGX code in Signal’s GitHub account. I assume that the software running inside the secure enclaves will be open source as well. Which will in theory allow us to inspect it and to flag any privacy issues.

Unfortunately, SGX is a rather obscure field of technology. So I suspect it will take an expert to validate that the source code matches the code actually running inside the enclave. After all, we cannot look at the code being executed, one has to go by its signature instead, trying to match it to a specific build.

Given Signal’s popularity, I totally expect some experts to do this. Once, maybe twice they will do it. However, it doesn’t seem that the enclave’s code will be completely maintenance-free. It will need to be updated frequently, and nobody will keep up with that. And then the users will on longer know whether the secure enclave they connect to is really running the code it should.

Conclusions

It is great that Signal is looking into solutions which both respect our privacy and are user friendly. However, in this particular case I doubt that they achieved their goals. There are just too many ways to compromise the SGX technology they build this solution on, so we are back to trusting Signal which we definitely shouldn’t have to. The approach was probably inspired by Google’s solution for Android data backups which IMHO suffers from the same shortcomings.

If you ask me, Signal should give up the complexity of their SGX-based solution. Instead, they should enforce strong passwords. Yes, the user experience will suffer. But the end result will be a solution that’s clearly secure, rather than a mesh of fragile assumptions that they have right now.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK