Why Siri Sounds A Little Off…

source link: https://medium.com/@samuel.c.danquah/why-siri-sounds-a-little-off-380352ac1417

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Why Siri Sounds A Little Off…

“For decades, technologists have teased us with this dream that we will be able to talk to technology and it will do things for us,” said Apple Fellow Phil Schiller on a cloudy October day in Cupertino, California. At the time, Phil was giving his keynote address during an Apple Special Event (you know, the thing that you hear about that happens in the fall when they tell you what new S’s, XR’s and Pro’s will be available during the coming year), and he relayed this sentiment in the ever-so-slightly arrogant tone indicative of an Apple Executive. During his introduction, Schiller stressed that he was fully aware of the voice assistant technology of the time, and that he was…underwhelmed. The paradigm of the era seemed to be to simply have the machine learn the syntax then execute the actions. No nuance or expansion could be provided by the user, and any attempts to do so would obfuscate, rather than clarify, the user’s intentions in the mind of the machine. All of this would change with the introduction of Siri, Apple’s new intelligent mobile assistant, which the technology giant claimed would help users accomplish tasks on their phone “just by asking.” Even at the time, Schiller and his team knew that the technology which they were developing was not inherently revolutionary. Siri never promised to be more efficient at taking notes for you or setting alarms than any of its competitors, but Siri did promise to do one thing: hold a conversation — or, at least, simulate a portion of one. Schiller and his team correctly identified the core issue affecting consumer perception of virtual assistants: could you really talk to it?

Years later, while watching Her, Senior Director of Siri Alex Acero breathed a sigh of relief when he recognized exactly what made Scarlett Johansson’s performance so powerful: despite playing a robot, Johansson made every aspect of her speech sound natural. Acero and his team sought to humanize the Siri experience, an endeavor that has been pushed further every year since. Nowadays, speaking to Siri is much more fluid than it was merely a decade ago, but even the untrained ear can still recognize that the sentences coming from our phone speakers are being “generated.” It just doesn’t quite match the fluidity of speaking to or hearing another human speak. Why is that the case? Even if it was the case ten years ago, why has technology not sufficiently improved since then to eliminate that discrepancy? In order to answer this question, it’s worthwhile to take a look at how Siri “speaks” to us, and how we speak to it.

How Siri Works

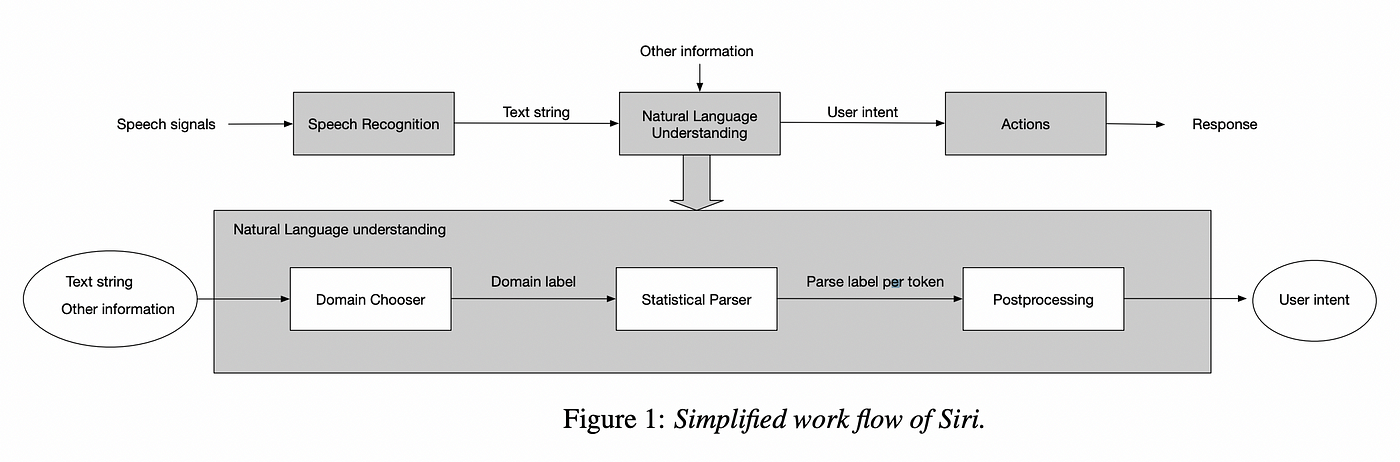

When you ask Siri something like “what’s the weather like today,” you expect a pretty swift response, and, equally as important, a response which is spoken back to you with the same casual tone which you used to address your phone initially. In order to even get to the point of producing a reply, Siri has to walk through a number of steps behind the scenes. The following chart illustrates this process a little better and looks pretty complex, but fear not as we will dive into the jargon and learn just what we need.

Chen at al., Active Learning for Domain Classification in a Commercial Spoken Personal Assistant

When you see those little circles dancing on your screen, Siri is actually progressing through the following stages:

- Speech to Text

- Speech Processing

- Necessary Action

- Text to Speech

How Siri Listens

Firstly, Siri has to convert your speech into text input, which is the actual form of data which the command execution component takes in. All this means is that the sounds picked up by the phone’s microphone are turned into a stream of waveforms, which are in turn classified into the words that they are intended to represent. In this sense, Siri picks up speech much like a human, by hearing sounds and recognizing the differences between sounds. At the same time, however, humans are capable of accessing more contextual information than Siri. Largely, Siri is capable of many aspects of “bottom-up lexical processing,” meaning that Siri intends to parse a sentence and figure out what each word means, then determine how the combination of the words fits together to form the intended meaning. Humans, however, also have access to “top-down processing,” which basically allows us to see into the future. With top-down processing, we can use higher level clues such as our independent background knowledge and the context provided by our environment to make better predictions about what someone is saying, especially when a sentence is ambiguous or may have several layers of implications baked in. Naturally, it is hard for any computer to be able to take in all of the ambient data in the world and compress it the way the human brain is able to, but it can certainly try.

In Siri, this processing is implemented in two different ways because of a very key feature of language: ambient voices vs directed speech. Sometimes, you will be engrossed in a conversation with someone, during which you are both aware that you are engaging in the conversation with each other. Other times, you may be busy doing something else when someone begins speaking to you. Studies show that even from a young age, we are able to pick out our names from dozens of ambient voices around us. In the latter scenario, you still need to be present enough to recognize you are being spoken to, and then immediately begin processing the context and sounds which follow. Siri takes the waveforms that enter your phone’s microphone and feeds them to a neural network (imagine a computer brain, but made of math) which assesses the probability that the sounds being heard are “Hey Siri.” There are several layers of processing that occur, during which the data is essentially stretched and contorted in every which way to ensure that a mistake is not being made. Afterward, there is a secondary checker which is even more powerful than the first probability checker to further ensure the likelihood of a “Hey Siri.” Immediately after a true positive “Hey Siri” is detected, the words that follow have to be deciphered in the same way that they would be had you opened Siri by pressing the home or power button. That second level of listening differs in that, since Siri is already aware that it is being spoken to, Siri needs to direct itself towards producing some output. You don’t normally think of conversations as a process of input and output, but your conversations with Siri will always be limited primarily by the fact that Siri has a purpose with each and every interaction. This processing level occurs a lot more like the chart above, and the generated text input is fed to a “Domain Chooser,” which is pretty much what we previously described as the “old voice assistant paradigm.” The Domain Chooser seeks to answer the question “what kind of information does the user want,” the same way you have to figure out what an SAT reading comprehension question wants you to figure out. Then, the data is fed to a “Statistical Parser” which seeks to figure out exactly what information is being asked for by breaking up the user input and assigning labels to each portion that will be used to determine potential actions Siri needs to carry out. Once this is done, an idea of the user’s desire has been generated and Siri can do what needs to be done. Except Siri doesn’t stop there.

How Siri Speaks

As discussed, much of the consumer appeal of Siri comes from the fact that Siri is able to speak back to us. Once the necessary action is determined, Siri is able to give users a voiced response which may be a statement confirming the commencement or completion of some task, a question probing for a more specific command, or even a joke. This is the heavily assessed part, because it is our only real way of confirming that Siri is as sentient as we desire it to be. Speech synthesis is insidiously difficult, and involves primarily a very large set of data that needs to be then chopped and spliced in different combinations in order to produce all of the necessary sounds. Siri will never say something like “the horse I saw yesterday ran into a tree,” but it needs to be able to, and in order to do so Apple has to record 20 hours of speech in a professional studio to get the highest quality audio. Take a look at this photo:

Siri Team, Deep Learning for Siri’s Voice: On-device Deep Mixture Density Networks for Hybrid Unit Selection Synthesis

Here, you can see sound waves on top and their corresponding spectrograms on the bottom. A spectrogram is a visual representation of a signal’s frequencies plotted across time. Remember how we mentioned that your phone’s microphone picks up a stream of waveforms? Well, any sound wave is actually made up of a bunch of different sound waves, each resonating at different frequencies and constructing and destructing composite waves as time passes. These spectrograms allow us to see all of these frequencies at once, which helps linguists and computers alike tell exactly which sounds are being produced as each sound is formed of a largely unique combination of frequencies, which are absolute regardless of the presence of additional noise (literally or figuratively) in the sound data. But once we can see all of these frequencies and identify certain combinations within them, what exactly are we looking for? Well, engineers at Apple go ahead and break up all of the sounds from all of the hours of data into “half-phones.” A phone is a distinct sound within a word, which may or may not be semantically relevant to the word. When a phone is able to by itselfbe the distinguishing factor between two words, then it is called a phoneme. But because there are so many different ways in which sounds can be augmented in order to match the prosody of a sentence, simply using the stored half-phones and connecting them cannot replicate human speech. This form of speech generation is called “unit selection” and is the main culprit behind robotic feel of many robotic voices. In order to combat this, Siri first determines the prosody of the response which it will give, then applies unit selection afterwards. This way, a more natural sound is produced when Siri chooses specifically the half-phones that match both the intended sound and the intended prosody of the response. Once these half-phones are all patched up, Siri is able to speak.

How Humans Speak, and How Siri can Improve

Here’s the TLDR: Siri listens by taking the sound input from the phone microphone and breaking this input into waveforms which are converted to text by making educated guesses as to which sounds are being produced by the particular combination of frequencies provided. Moreover, we know that Siri speaks by determining what it would like to say in text form, and then deciding what tone and cadence it would like to portray with the response. Afterwards, Siri selects certain sounds from its database and stitches them together to form the speech which is produced. We know that this speech sounds weird to us because it doesn’t reflect the manner in which humans speak. Humans are able to store the phonology of a word in the mental lexicon, which attaches sounds and meanings to words within our brain. Through a combination of bottom-up and top-down processing, we are able to modulate our volume, tone, and cadence in real time as we speak. Even without a clear view of what we want to say next, we are able to sort of reverse engineer our sentences such that they sound correctly intonated every single time. Siri is very far from this ability.

However, it is because Siri and voice assistants like it are unable to replicate human speech production that large companies like Apple, Meta, and Google are incentivized to channel resources into more research. At Apple, the most recent iterations of Siri have incorporated a neural network to the speech synthesis process. Features of speech can either be stable and well-spaced (like with vowels where diphthongs are few and far between) or can change pretty quickly (like with the transitions between voiced and unvoiced sounds), so this neural network takes into account the fact that there should be these variances within each sentence and seeks to determine what the proper sound should be for each of Siri’s responses. In the future, we will likely see more and better layers added to this neural network (along with additional training data) that can allow Siri to better guess how a human would say a specific phrase depending on the standing context. As mentioned, the fact that interactions with Siri are short and purpose-driven significantly affects the learning rate. Context is much harder to glean from one or two sentences than from an entire two minute conversation, although maintaining a relatively professional tone (especially since Siri expects to carry out a task) will always be to Siri’s benefit. The range of contexts is heavily restrained to this general area, which is what allows the domain choosing process to work successfully.

Sources:

Active Learning for Domain Classification in a Commercial … — Arxiv. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1908.11404.pdf.

Carmody, Dennis P, and Michael Lewis. “Brain Activation When Hearing One’s Own and Others’ Names.” Brain Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 20 Oct. 2006, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1647299/.

“Deep Learning for Siri’s Voice: On-Device Deep Mixture Density Networks for Hybrid Unit Selection Synthesis.” Apple Machine Learning Research, https://machinelearning.apple.com/research/siri-voices.

“Hey Siri: An on-Device DNN-Powered Voice Trigger for Apple’s Personal Assistant.” Apple Machine Learning Research, https://machinelearning.apple.com/research/hey-siri.

“How Does the Brain Process Speech? We Now Know the Answer, and It’s Fascinating.” Big Think, 19 Apr. 2022, https://bigthink.com/mind-brain/how-does-the-brain-process-speech-we-now-know-the-answer-and-its-fascinating/.

Pierce, David. “How Apple Finally Made Siri Sound More Human.” Wired, Conde Nast, 7 Sept. 2017, https://www.wired.com/story/how-apple-finally-made-siri-sound-more-human/.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK